Foreword

Exhibitions or collections of photographic portraits do not as a rule require written explanations. The pictures speak for themselves, their stories told by the manner in which the photographer has captured his or her “models”, the environment in which they have been placed and their facial expressions. An introduction is, however, necessary in the case of Pavel Hroch’s project Fifty faces of resistances. It presents people who over a span of many decades stood up to evil, inhumanity,...

- See the exhibition

- Read the whole text (PDF, 0 kB)

Authors of the exhibition

Author of the project and photographer: Pavel HROCH / Authors of texts: Adam DRDA, Luděk NAVARA, Jiří PEŇÁS, Jan HORNÍK / Author of the online exhibition: Eva CSÉMYOVÁ / Proofreading: Michaela ŠMEJKALOVÁ / Translation: Ian WILLOUGHBY / We would like to thank Mr. Freud ARIAS-KING without whose support the project The Faces of Resistance could not be realized.

- Read the whole text (PDF, 0 kB)

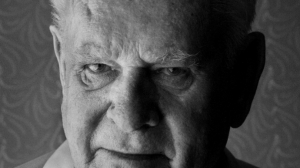

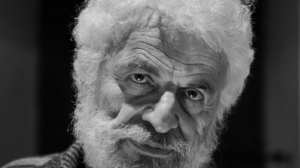

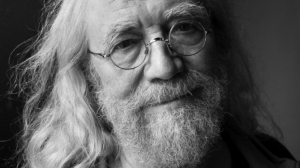

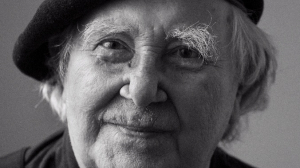

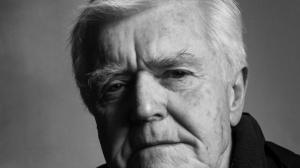

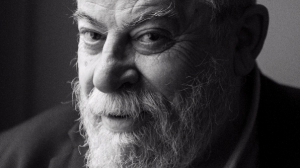

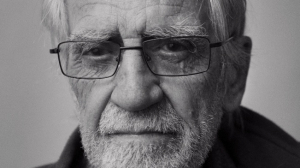

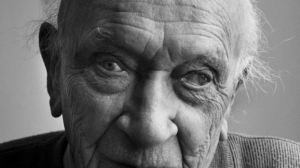

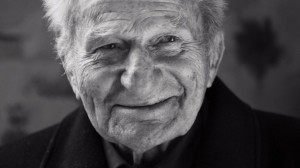

Alexander BACHNÁR (*1919)

“The Holocaust didn’t start with the loading of Jews onto cattle wagons. It started in the moment people gave Jews slaps with impunity. What we call the Holocaust, the concentration camps, was just the conclusion of the Holocaust. But it began with that first slap. So it teaches us that it’s necessary to start fighting evil as soon as the first slap.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

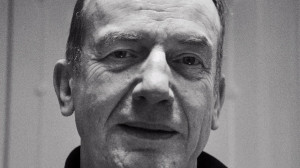

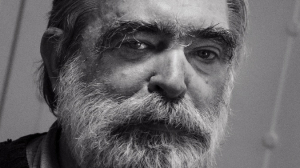

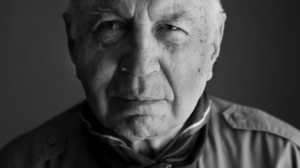

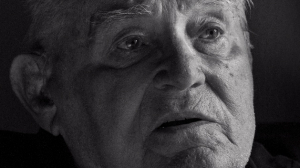

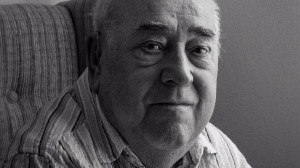

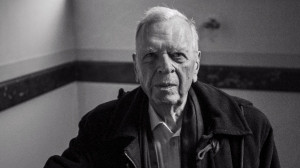

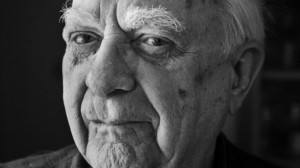

Milan BALABÁN (*1936)

“The best job was with the Prague sewer system. Admittedly we were underground, but you could at least make some money. The work was relatively dangerous. You couldn’t slip – otherwise the sewer would carry you all the way to the Vltava. A couple of workers died that way. You also lost your sense of smell in the sewers. Mine came back two years after I changed jobs.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

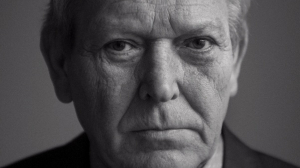

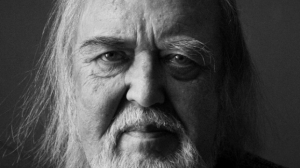

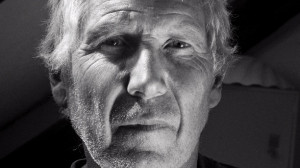

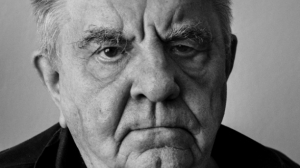

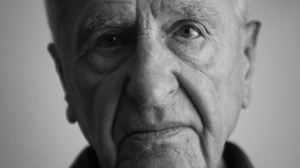

František BENEŠ (*1928)

“They started to follow me, to badger me. They later put about a rumour in Orlová that I had helped someone cross the border. People started avoiding me. So I said: It’s time to scarpe.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

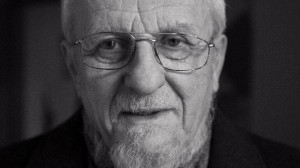

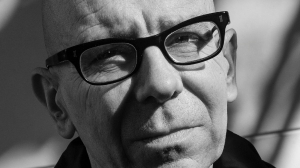

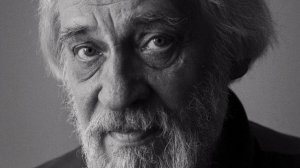

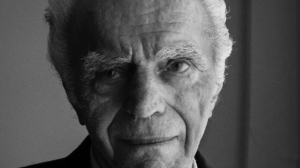

Anna BERGEROVÁ (*1929)

“When the front passed they advised us to go to Poland for delousing and to rest. Mum wanted to go home at any price. When we arrived we discovered that our whole village had been burned out.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Emil BOČEK (*1923)

“Once during a flight I saw the red light flashing. The fuel wasn’t working! I was wondering whether to turn back. I decided to return. Some fifth sense told me to climb. Then the engine really started to fail and I thought I’d have to jump… At that moment I was above the sea. Naturally I had a parachute, but entering the Channel in November isn’t that appealing…"

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

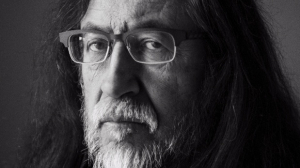

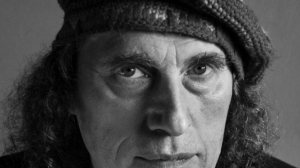

Vratislav BRABENEC (*1943)

He was involved in a landmark 1976 court case when he and friends were found guilty of “expressing disrespect to society and disregard for its moral principles” by “in particular the systematic repetition and emphasis of vulgar phrases”. Brabenec, Pavel Zajíček and Svatopluk Karásek received eight months while the repeat offender Jirous got a year and a half. The process resulted in the creation of Charter 77, which Brabenec signed on his release from prison.

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

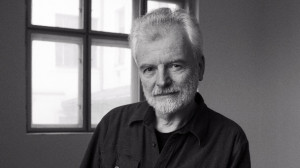

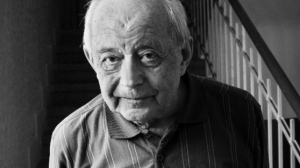

Pavel BRANKO (*1921)

“For me the antithesis of expanding fascism was the Soviet Union, whose seamy side I didn’t have a clue about, though even then it was possible to find out about it. But people reach for the sources that chime with their own convictions.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Pavel BRATINKA (*1946)

“You were scared, but it was never overwhelming. The laws were elastic – they could lock you up any time. I refused to testify.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Eugen BRIKCIUS (*1942)

“I signed it because I realised that if I had written the text myself I would have written something similar. I lived according to the Charter my whole life, even without it existing.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

František BROŽ (*1939)

“They didn’t act directly, for instance. You can’t imagine what they came up with. For instance, they banned threshing during the day, saying there was an electricity shortage. So that the unified agriculture cooperative would be able to thresh at the same time. They also changed the layout of the land. By this I mean they took one field from us and gave us another. But the new field was worse, further away than the first one. Their explanation was the co-operative needed the original field....

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Ján ČARNOGURSKÝ (*1944)

“The revolution had to come. It was only a matter of how it would occur in our case. Communism had already fallen in the surrounding countries. In Germany they’d knocked the Berlin Wall down on 9 November 1989. The Hungarians were letting East Germans into Austria. Poland was run by the government of […] Tadeusz Mazowiecki. In the Soviet Union Mikhail Gorbachev had launched perestroika and even there huge changes had occurred. The isolated Communist regime in Czechoslovakia couldn’t hold on.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Vlasta ČERNÁ (*1933)

Fortunately Vlasta, being a minor, didn’t face torture. But they did lock her up in solitary confinement in an underground cell for three months. “For the entire duration of the investigation I wasn’t able to wash or change my clothes. I felt like an animal. It was humiliating. To kill the time, I sang in my soul all the songs I knew. I prayed… Otherwise I’d have gone insane.” Vlasta had to write a fake postcard from Austria so her parents would think she was safely over the border.

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Zdenko ČERNÍK (*1932)

“After four blows you’d say whatever they wanted. For instance that you’d murdered your mother with a chain. I remember the four blows but nothing more. Whether I received more, I don’t know. But I do remember that I didn’t know what they wanted. They kept demanding some contact from us. We slept on tables and so on.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Mikoláš CHADIMA (*1952)

“Originally I wanted to play the bass. Four strings – the fewer the better. But in ‘69 I had an incident that concluded with an insult to the head of state and an allied state. When they came for me, and my parents knew nothing as I hadn’t told them anything, my father thought they were after him and threw several of his illegally held pistols in the river."

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Jaroslav CHNÁPKO (*1956)

“Víska was exceptional in that samizdat was created there secretly but on a large scale. There were maybe 100 people there, though in one room sealed with mattresses; printing took place on a mimeograph without visitors knowing. You turned a handle on that machine and with every turn one page was created. It was loads of work. But the police never found anything.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Silvestra CHNÁPKOVÁ (*1954)

“After the revolution all kinds of people started to say hello to us. I founded the Civic Forum in Osvračín and people asked me if I’d be the mayor. I think some were afraid that we’d want to get them back for what they’d done to us. But naturally nobody apologised to us. With a few exceptions, the locals kept their distance.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Zdenko FRANKENBERGER DANEŠ (*1920)

“We never learned why. We never received his ashes. But my aunt, his widow, received a visitor after some time. A German officer visited her and handed her a bill for uncle’s execution. Uncle’s death broke me. I was afraid. I was ashamed of my fear, but I knew that fear was stronger than my will, conscience, faith – basically I failed to cope in that instant. I began putting buttons in my shoes and walking on them all day to get used to bearing pain so as not to give anything away during the...

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

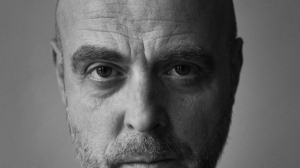

Stanislav DEVÁTÝ (*1952)

“When I think back, perhaps the worst thing was when I began a method of passive resistance. At that time I wrote a protest letter to President Gustáv Husák. Secret police officers were monitoring me and expected that I would go to a restaurant in Zlín, that I’d drink. But I didn’t drink. It was some time in 1983. A birthday party was taking place in the restaurant and they came for me. They arrived around midnight. It was a better restaurant – even foreigners used to go there. They came for...

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Levko DOHOVIČ (*1936)

“So it began. Uzhhorod, Lviv, Kiev, Kharkov, then the same route back. Because some paper always had to come directly from Moscow regarding where minors were to be placed. In Kharkov, where they had taken me to a camp for minors, the chief warden said he didn’t want me.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Bohumil DOLEŽAL (*1940)

“Jan Lopatka and I wrote that the whole of official literature post-1948 was a Potemkin village, that it was a simulation of literature and, what’s more, was ideologically trussed. (…) Though I was far from the most important person – that was Mandler, and then people who were far better educated and had better orientation than us, meaning Němec and Hejdánek – I was the direct cause of a quick kerfuffle. First I wrote that the chairman of the writer’s union, Jiří Šotola, wrote...

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Ailsa DOMANOVÁ (*1927)

“They wrote that it wasn’t in Czechoslovakia’s interests for them to let me go. I had worse pay than a cleaner. I worked for three years as a seamstress – I resewed smelly old things, fur coats… Of course they gave me such work on purpose. They were punishing my husband through me. Also by not letting me go home.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Vladimír „Lábus“ DRÁPAL (*1964)

“The police were constantly hassling me. Constantly. They came to my work. When there was something happening they picked me up at 5 in the morning and I sat in the cop shop till 8 in the evening. Often they didn’t want anything, I just sat about and they brought me some police almanacs to read. Naturally it was unpleasant. […] It sometimes happened that I left an interrogation, ran down the steps and after 50 metres other StB men came after me and arrested me. I said: ‘I’m just leaving an...

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

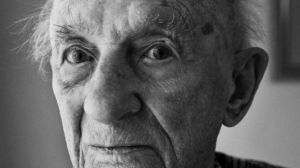

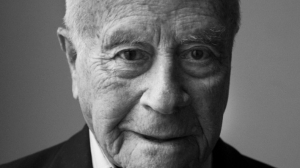

Imrich GABLECH (*1915 - †2016)

“I fainted when I landed and a British officer called me to his office. I still hadn’t mastered English properly, so my communication was just so-so. He poured me a whiskey and asked what the problem was. I said I had returned from the Gulag. He was angry that I hadn’t said so immediately. I should have brought it up. But I defended myself. I said that we were a small state and I had escaped to fight. That I wanted to fight… I didn’t escape to hide somewhere… This was...

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Fedor GÁL (*1945)

“I was born in an odd place – the Terezín concentration camp. I was lucky in that my pregnant mother, along with my brother who was five years older, arrived there on the very last transport at Christmas 1944 and I was born around three months later. […] Our transport from a camp in Sereď was headed for Auschwitz, but as it was already the end of the war and the gas chambers and crematoriums had stopped working they turned us around and we reached Terezín. It sounds strange and absurd, but...

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Jiří GRUNTORÁD (*1952)

“It was never possible to get all the work done and it was always cold, too… In October it started to snow and in May it was still snowing. They harnessed the prisoners to a snow plough… It’s hard to describe… The first time I entered the workshop of the Preciosa national enterprise I thought I was in hell. In the clouds of steam I saw figures running about incredibly, dressed in some kind of rags of overalls. And in a while just like them I too was running about.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Karel "Kocour" HAVELKA (*1951)

“I got a uniform with a green stripe, which meant I was regarded as a would-be escapee. So I never got outside the prison building, even to work. The first day I came to work I got a fright. They all had towels wrapped around their heads. There was terrible noise, steam and a stench from the vapours. It put me in mind of Dante’s Inferno.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Miluška HAVLŮJOVÁ (*1929)

“Then one day they took me off to an interrogation centre. There they hung my clothes on a hook and an StB supervisor said: ‘Go look out the window!’ A woman with a pram was walking along the pavement and in the pram was a child the same age as my child at home. It was probably the worst moment of my life."

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Vladimír HRADEC (*1931)

“After an interrogation, they always pushed me into a cell. Somebody was sitting behind the cell door tasked with making sure I didn’t fall asleep. I had to keep walking. Any pause in walking throughout the day would mean loud kicks on the door and the order ‘Walk!’… After a week or two it was a case of ‘sleep while you walk’.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Tomáš HRADÍLEK (*1945)

“We were worried about the children. That’s why my wife didn’t sign the Charter. Otherwise they could have taken them from us and put them in a children’s home.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Vladimír HUČÍN (*1952)

“Ahead of time Vlastimil Švéda and I placed five-kilogramme teargas canisters with timers in two dustbins. When they started to play the Internationale, smoke began to bellow out of the first bin. Unfortunately the second canister burned out. Its heat made the bin glow red hot and no smoke emerged. Just one teargas canister was sufficient for the whole event to be cancelled… The smoke blew over a military orchestra that was playing with enormous intensity. They tried to keep going.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Čestmír HUŇÁT (*1950)

"The Jazz Section essentially escaped from regime control. We published books that weren’t subject to censorship. It was the same with concerts, at which new wave bands who weren’t allowed to make a living from music appeared. The membership base comprised a dense network of active people, which the State Security didn’t take too kindly to (…) Our ever-growing international cooperation also annoyed them.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Jaroslav HUTKA (*1947)

His father died in Czechoslovakia behind the Iron Curtain. “I was in exile and couldn’t go to the funeral. It made me feel so bad that I thought I’d become sick and went to a doctor in Holland for the first and last time. It’s a long story, but I left him healthy and in a pretty good mood.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Vlasta JAKUBOVÁ (*1925)

Vlasta again became a messenger but also began transcribing reports herself. She wrote them in invisible ink on love letters that she sent to a made-up address in the Netherlands.

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Martin JANEC (*1922)

“This is the most valuable ID that I received and that I possess,” Martin Janec says respectfully, showing the ID card he was handed by Ján Golian himself. Janec was one of the few that accompanied the great commander to the very end.

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Jan JANKŮ (*1921)

He has never forgotten a chess game with a fellow prisoner awaiting the death penalty. The prisoner’s name was Miloslav Pospíšil and he came from Bystřice pod Hostýnem. "The chess game was developing nicely,” says Janků. “We were around the middle of the game. Suddenly the door opened and they called out: Pospíšil! I wanted to shake his hand, but they wouldn’t allow it. So he just kind of touched my arm a bit. And the game remained unfinished."

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Miroslav JIROUNEK (*1955)

“He tapped the table with the rubber end of a pencil and asked: ‘So what can you tell us, Mr. Jirounek?’ And I said to him: ‘What the hell are you on about, Vláďa?’ Vláďa turned red and left the room. Textbook-style, he was replaced by a bruiser. He grabbed my notebook – that infuriated him most – bore his teeth and roared that he would smack my head off the radiator. I told him to have a go and, surprise, he didn’t do it.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Jiří KABEŠ (*1946)

“Mejla and I always said that it’s better to play good music badly than overblown crap.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

David KABZAN (*1969)

“During my final interrogation […] he […] beat me for four hours. He first banged his truncheon against a metal locker and then beat me in the neck and the head. I was sitting on a chair and beside it there was a plank bed. When I couldn’t take any more I rolled over onto it. I got a fair few more blows of the truncheon on the bed. He beat me for a long time. Then the StB men went for lunch and assigned a guard to me. They came back and carried on. They wanted me to sign some statement. For...

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Peter KALMUS (*1953)

“They took the tablet. They brought me to a police station and questioned me in connection to it. I confessed to having made it and requested that they return it, as it was my property. They agreed, but I wasn’t allowed to carry it through the streets just like that, as it was propaganda for the West. So I wrapped it in a newspaper – Rudé právo – and brought it home.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Svatopluk KARÁSEK (*1942)

“I always say that politics is essentially an aspect of faith, that we are responsible for the era in which we live. (...) After all, it’s not enough to be hidden away in some church, to say the Lord’s Prayer and to let on that I don’t have anything to do with what’s happening around me. I’m for Christians feeling responsibility and being engaged."

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Ivan KIESLINGER (*1928)

“A tank came up to where we were. I had been sent to Wenceslas Square – and I was supposed to shoot at it with a bazooka if it got close. I hid in the toilets and a friend gave me a signal. He was standing on the corner (…) and in his hand he had a large mirror via which he observed the machine. The Germans in the tank evidently didn’t have a sense of humour and shot the mirror out of his hands."

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Josef KLEČKA (*1930)

“On the afternoon of 4 May a still unknown to me companion gave the order for me to not leave the cottage. Before he left he pointed to a wardrobe full of guns, so that I could defend myself if somebody attacked me. Then he left."

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

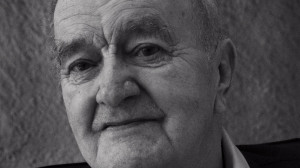

Ivan KLÍMA (*1931)

“I was a member of a criminal organisation, without having committed any crime myself. But of course due to my membership I did bear a certain responsibility. I knew that’d I’d have to make up for that until my death.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Pavel KOHOUT (*1928)

"It had been a mistake of the intellect, not morality. The whole of the rest of my life has been devoted to righting that contradiction. People have the right to make a mistake – what’s important is identifying and not repeating it.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Felix KOLMER (*1922)

“I remember the arrival well. The dawn began and on the ramp there were people in prisoners’ clothes. That was the first time I had seen such prisoners’ clothes. (…). A man approached me and said: ‘There’s no escape from here. The only way you’ll leave here is via that chimney.’ I thought he was off his rocker. I didn’t understand where I was. My brain just didn’t take it in. Later I saw that on one side, walking in rows of five, were children and old people. Those were people over 42. And I...

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Jan KONZAL (*1935)

“In the night, when I was asleep, they took away the priests. But when they woke us in the morning I was suddenly the second oldest at the monastery as a 15-year-old. They had taken those aged 16 and older with the others. My two brothers too."

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Miroslav KOPT (*1935)

“I went to work to hand in a sick note so I’d get a few days’ head start. At the office five men jumped on me and it was all up.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Vladimír KOUŘIL (*1944)

“Karel Srp was no longer in contact with us at that time. He had distanced himself from us. Those of us from the inner circle of Jazz Section are still a little traumatised by it.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Marie Rút KŘÍŽKOVÁ (*1936)

“I immediately declared allegiance to Charter 77 on 13 January 1977, not only with a signature but also with a letter in which I responded critically to the […] piece Losers and Usurpers, which had been published a day earlier in Rudé právo. I sent the letter to President Husák, the media, my employer, various institutions and to the schools where I had previously worked. During an interrogation the StB showed me that they’d automatically forwarded it from those schools to the State...

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Miroslav KUSÝ (*1931)

“The outcome of the investigation fully proved also the subversive activities of Dr. Miroslav Kusý. With his essays, editorials and articles sent in the course of 1989 to be made public on the radio stations Radio Free Europe and Voice of America he actively joined the leadership of the psychological war against our country and our system.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Ivan LAMPER (*1957)

“I was aware that most domestic samizdat was oriented toward culture, history or feuilleton-style pieces, such as the then samizdat Lidové noviny. Reports about current events or life in Czechoslovakia appeared here and there on foreign radio. […] We wanted to do normal journalism, to write truthfully about people and their stories […].”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Marta LIČKOVÁ (*1926)

“Around a week before the occupation we returned home and everybody was saying they’d invade, that troops were already assembling. They had information to that end. So we said at home we’d think it over. But how would the Russians occupy us. We still didn’t believe it.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

František LÍZNA (*1941)

“He found out I’d been inside and said to me: ‘Son, on you go, get married and start a good Catholic family.’ I was adamant, so the vicar called the state commissioner or the church secretary or whatever the function was called to discuss my case with him. Of course the commissioner was an StB man. He started coming out with some nonsense to me and I told him I wasn’t interested, that he should tell me straight whether there was any way that I could study. So he told me completely openly that...

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Břetislav LOUBAL (*1931)

It was 13 September 1950. During a class the door opened and the caretaker was standing there. He told Loubal he was to go to the director. But the caretaker had been forced to the door by secret police officers standing behind him. On both sides of the door. “They immediately grabbed me, so I couldn’t escape,” says Loubal. He was aware he had couldn’t have anyway. “I couldn’t jump out the window – the classroom was on the third floor,” he explains.

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Václav MALÝ (*1950)

“I regarded the emergence of Charter 77 as a great liberation, because for me it was a kind of impetus to finding a way to clearly express my disagreement with the then system. Naturally I didn’t pull any punches even in sermons. However, I didn’t have directly political sermons – they reacted naturally to the atmosphere of the time but were always based on the Gospel. When Charter was founded it helped me express my civic responsibility.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

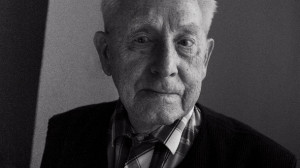

Eduard MAREK (*1917)

“In my mind I built a scouts centre on Rohanský Island. I found a pencil and drew it all on toilet paper. I managed to smuggle the sketches home.” A move to the Mariánská camp in the Jáchymov area followed.

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Zdena MAŠÍNOVÁ (*1933)

“What was the hardest moment for me? The fate of our mother, who died in a Communist jail in appalling circumstances in 1956. After arresting her they left her without medical care. They had arrested her in 1953. We discovered that they left her lying on a concrete floor in a terrible state… That was the worst time.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

František MIKLOŠKO (*1947)

“One specific moment was important for me, when I became involved in the secret church in the time of the dissent. I was deciding at that time whether to secretly go for the priesthood and become a clandestine priest, or to be active as a lay person. Life showed that I didn’t become a priest and that’s how it was meant to be.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Jaroslav MOJŽÍŠ (*1934)

“My clothes in Jáchymov seemed to be a uniform from the old Austrian period. There were patches in six different colours. It wasn’t possible to fasten the waist so the electricians made me a belt out of cable. We got a rusty bowl for food. And we gathered uraninite into barrels by hand.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Rudolf MRÁZEK (*1934)

“Apart from school, scouting was our main daily enjoyment. There we learned friendship, generosity, kindness, love of homeland, to defend it – all of this part of scouting. And they banned it because they didn’t need love of homeland, they needed love of the Soviet Union.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

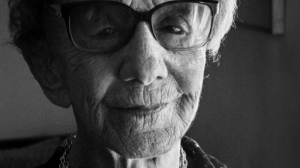

Františka MUZIKOVÁ (*1933)

“The lice – that was terrible. They brought us from Slovakia to Pankrác in Prague and deloused us, so I walked around the prison courtyard at Pankrác with a turban on my head. You know, today it may seem like a detail in the overall context. But even there in prison I really hadn’t ceased to care. You get used to prison, but it’s hard to get used to them taking away your dignity […].”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Dana NĚMCOVÁ (*1934)

“We created a world within a world. It was like what was written on one Plastic People record – The Merry Ghetto. We enjoyed lots of good times that compensated for the pressure and kept us going when it came to resisting and insisting on this independent alternative.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Otmar OLIVA (*1952)

They put two other soldiers on me, agents who informed to the military counterintelligence. They charged me with incitement and distributing Charter 77 materials,” Oliva said. He was imprisoned for 20 months. It was the test of a life-time. The worst thing in prison was the cold. Oliva says he found God during his time behind bars. He also managed to capture this trying period in drawings. His attorney Josef Krupauer offered to smuggle them out. But how? They wondered whether it would be at all...

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Karel "Fidelius" PALEK (*1948)

“The editorials in Rudé pravo [until 1990 the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia’s main instrument of propaganda – ed.] raised the issue of Communist language as a subject for reflection of current life experience. What function does that language fulfil? (…) What does it actually speak about? Does it speak about anything at all? Do all of those – often bizarre – linguistic expressions delivered by Rudé Pravo make any sense? I soon realised that a certain order prevailed in Communist...

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Viktor PARKÁN (*1946)

“I got to know lots of excellent people I wouldn’t have met otherwise. I didn’t go into exile and remained free on the inside.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Petr PLACÁK (*1964)

“They arrested me before I could even reach the monument on Wenceslas Square. When myself and others were waiting at the cop shop in Benediktská St., I wrote on a piece of paper that we’d gather again the next day. The reason was a ribbon which I’d hidden in the lining of my coat and which had ‘To Jan Palach from Czech Children’ written on it.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Jiří POŘÍZKA (*1940)

The second time was when in August 1968 he and his wife fled the Soviet occupiers into exile and left behind their little daughter Pavlína, whom the Communist regime refused to let join them in their new home in Sweden. He began fighting the totalitarian regime, this time over the right to live with his daughter… “I wanted to take a firm stand against the regime,” he says. He and his wife decided to go on hunger strike to win the right to have their daughter join them in Sweden. It was a minor...

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

František Vincenc PŘESLIČKA (*1933)

“I did it all because I didn’t want the Communists to rule here. I just couldn’t agree with that. But as a Christian neither could I agree with the position that the Church began to take.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Jan PRINC (*1948)

“We just wanted to live in our own way and within the framework of the laws of the time. We actually did things that were a service to the state. We educated people who had got out of prison and were looking for work. Today we’d get a grant for such a community centre.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Květoslava PRINCOVÁ (*1950)

“We discussed politics. I also copied books. We spoke about them and lent them out. For instance by Solzhenitsyn, who was banned.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Miloš PROCHÁZKA (*1928)

They were equipped with a transmitter, an encryption key, invisible ink and false papers. Each also had a capsule of poison, in case the worst came to the worst. “We were to bite on the capsule if we got into an impossible situation,” says Procházka.

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Bohumil ROBEŠ (*1930)

"They thought up every possible kind of harassment for me. They really put some thought into it. They were primitive. I told them they’d answer for their crimes against political prisoners. So they set on me and tied me to a stake, with my feet backwards and my hands tied constantly for 10 hours. They then untied me at 10 in the evening and gave me an aspirin. I went to my cell…"

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Jan ROMAN (*1929)

“The worst thing was my capture. Two StB men caught me. They arrested me in front of the train station. They came after me and asked my name. In those days, people saw spies everywhere. Evidently I too had been suspicious to the priest. The moments when they caught me were the worst.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Jan RUML (*1953)

“They charged me with subversion. At first I found imprisonment quite tough, as Rudolf Battěk had received seven years. I expected a similar sentence.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Jiří RUNKAS (*1955)

Though the idea of flying across the Iron Curtain was daring, it appealed to Jiří Runkas from Moravské Budějovice. He was aware that the Slovak road cyclist Robert Hutyra had succeeded in doing so and had indeed been inspired by another balloon escape from the then East Germany to the West.

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Miloslav RŮŽIČKA (*1925)

“I duplicated leaflets on a typewriter and then distributed them to people I knew I could rely on. One time I ran into a neighbour. He said some declaration had appeared stating that distributing printed materials wasn’t allowed. He also said that if anybody received such a leaflet he was to report it. Then he asked if I by any chance I hadn’t written it. So I confided in him. I told him I had written it and that he wasn’t to discuss it with anybody. But by coincidence they arrested him and...

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Štefan RUŽOVIČ (*1934)

“I’ve known Pankrác, Leopoldov, Ilava, all the best spots,” says the political prisoner today in a hoarse voice. However, he spent the greatest part of his prison pilgrimage in the now almost forgotten labour camp of Rtyně v Podkrkonoší, known as the Dark Mine.

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Karel SCHWARZENBERG (*1937)

“My view is you shouldn’t either be ashamed or build yourself up on the basis of who you are. Just say – God has placed you here, get on with it as best you can.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Karol SIDON (*1942)

“A few days after the Charter, an article about the writer Ludvíki Vaculík appeared in the magazine Ahoj na sobotu that showed him in an unflattering light. It was clearly the work of the State Security. I took a small pair of scissors and clipped that piece about Vaculík out of individual copies and decided that I’d only sell the magazine with the pages cut out and then just to those I knew by sight. I had a hunch they’d test me. After a while a young guy came along and I thought: ‘You’re...

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Jiřina ŠIKLOVÁ (*1935)

“I always just organised a garage with somebody where the consignment was to be brought. Then I met the courier (…) and told them the address where they were to arrive by car at a given time. The car with the courier then went inside or parked near the garage and then loaded or by contrast unloaded the consignment. The garages alternated. Sometimes it was a garden or cottage, a small house. Quite often it was an Evangelical rectory, where foreign cars could also arrive without being really...

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Oto ŠIMKO (*1924)

“It’s impossible to describe the change in the feeling inside. Imagine, I’ve got a rifle in my hand and I’m fighting my persecutors and executors. We’re on the same level. In other words, I’m a free man internally. So I too can fight against that evil.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Miroslav SKALICKÝ (*1952)

“What’s more, I had just had a child at that time. From a young age, when she was six months, I had her with me during interrogations. In Kadaň they threatened she could be run over by a car or that our house would go on fire. Which in some cases happened. After a Plastics concert they set the building where they’d played alight. In Rychnov they blew a house up after a concert. […] So I said to myself that it wasn’t worth it here.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Věroslav SLÁMA (*1930)

On 21 October 1952 a second trial took place – as revenge for the escaped spy Cyril Sláma Jr. Cyril Sr. got another six years on top of the 14 he already had. His wife, the two brothers’ mother, received 11 years. Veroslav Sláma’s wife got six. Her father even got 10 years. Other relatives of Sláma’s, 13 in total, were also convicted. In all they were sentenced to 74 years in jail.

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Jana SOUKUPOVÁ (*1958)

“When I think about the reason I got mixed up with the dissidents the word detestation comes to mind. The pressure of normalisation was for me, first and foremost, disgusting. The design of its instruments of propaganda was gross and the faces of the vast majority of the governing elite betrayed heinous personal preferences that I just wanted to get away from – to the other side.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Dalma HOLANOVÁ-ŠPITZEROVÁ (*1925)

“You were forever in the shadow of death, because these were times when many of our friends and acquaintances were being deported. To avoid being driven insane by it all we did theatre there.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

František "Čuňas" STÁREK (*1952)

“From around sixth grade myself and a few others led a struggle over the length of our hair. Sometimes the principal would catch us, give us two crowns and say: you, you, you, to the barbers! (…) Hair started to become very important for us.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Ondřej STAVINOHA (*1955)

“I got as far as the fountain. The detonation was such that it propelled me forward somewhat. When the boom occurred I turned and saw Gottwald falling to the ground. At the same time glass and windows shattered and I thought to myself: I’ve gone too far! […] As I later discovered, the explosion ruptured the crotch of the statue and, if I remember right, ripped off Gottwald’s right leg. In the end I paid for all the damages, including the repair of Gottwald.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Jiří STRÁNSKÝ (*1931)

“When I had the morning shift from 6 to 2 pm, they woke you at 3 in the morning and you returned in bits at 3 in the afternoon. After work people could talk in their rooms. Four of them sat and spoke. I observed. I rarely said anything. I was glad they let me stay. They were a lot smarter and better educated than me. (…). There was an excellent art historian, Bonny Falerský, and he ran an art history seminar. We made a deal with a civilian, who bought all the postcards reproductions of works...

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Drahomíra STROUHALOVÁ (*1930)

In prison she was placed among prostitutes. “It took more than two months. I didn’t wash or change. I was so revolted you can’t imagine.” This was probably her lowest point.

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Ladislav SUCHOMEL (*1930)

“I experienced the greatest fear in the Cejl prison before going to court. They told me my lawyer was there and he questioned me as if he were an StB man. I asked how things looked. He said the death sentence was proposed for the first six. I was second in the text of the arraignment."

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Jan TESAŘ (*1933)

“I was writing my articles about Czech political compromises and so-called lesser evil that becomes the greatest evil back in autumn 1967. They weren’t based on an impression of Dubček’s policies but the study of history and were intended as a warning. They were also circulated in spring 1968. It’s not my fault nobody listened to me. Many times I warned of outcomes that every reasonable person could have expected, always in vain. Naturally I supported the Dubček leadership, even though I knew...

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Anna KOUTNÁ-TESAŘOVÁ (*1933)

“I refused to confess. I didn’t want to speak. But they got to me through the children. They said, ‘It’s up to you. If you don’t admit it you’ll be here longer, the children will be without parents’ […]. I testified. I confessed. Dozens of women did copying. Whatever they laid before me I took on myself, to protect the others[…]”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Anton TOMÍK (*1932)

“My faith helped me most of all. I’m a Christian and I survived thanks to prayer. I kept reciting prayers – otherwise it would have sent me insane.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Jáchym TOPOL (*1962)

“I don’t know if they had a hunch we were ‘political smugglers’. I think they more likely expected we had vodka, salami or something like that on our backs – and they were surprised when they found literature […].”.

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Branislav TVAROŽEK (*1925)

“The worst thing about being locked up was that from your free life they suddenly put you in a two-and-a-half metre by one-and-a-half metre cell where you have to be without all the things that you were used to. The arrest was all the worse for coming after liberation, when life was gaining momentum, everybody was doing their best, doing what they could.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Vlastimil TŘEŠŇÁK (*1950)

“They drove me out with harsh interrogations. The waste of time, exhaustion, fear, hopelessness. (…) They arrested and beat me whenever they wished and could. It was their job description. Comrade Kafka and another StB officer I didn’t know carried it out, pissed drunk. When comrade Kafka beat me in 1981 and I collapsed Kafka ran through another office to the corridor for a doctor. In the neighbouring office they were actually interrogating my good friend Pavel Brunnhofer. Banned music...

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Milan UHDE (*1936)

Host was banned in 1970 and Uhde himself was officially banned in 1972. Two years later the Divadlo Husa na provázku theatre directors Peter Scherhaufer and Zdeněk Pospíšil offered him incognito work in the form of dramatisations of well-known literary works: Párala’s Professional Woman, Mrštík’s A May Fairytale and Olbracht’s Nikola Šuhaj, Bandit; under the title Ballad for a Bandit, the latter became one of the theatre’s most successful productions and in musical film form became a...

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Miroslav VODRÁŽKA (*1954)

“A totally screwed-up situation ensued, because they employed insulin treatment on me. Today that ‘scientific’ method is banned, but they strap you to a bed and, via injections, you get ever increasing doses of insulin in your body […]. That causes hypoglycemic coma accompanied by hallucinations, thrashing about, cramps, etc. […].”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Jaroslav VRBENSKÝ (*1932)

“My imprisonment affected my mother’s psychological state and health most severely. But my time in jail also had its upsides. I would never have met so many exceptional people.”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

František WIENDL (*1923)

“When father was arrested, his acquaintance, who wanted to be brought to the West, came to us. Apparently father had agreed with his friend in Cologne that he would assist people in escaping in this way. But now, after father’s arrest, it was a new situation. I let him sleep over and in the morning Josef Touš, who was a train conductor, tried to guide him. But Schneider evidently didn’t keep his nerve and didn’t follow orders, so Touš refused to take responsibility. So I decided I’d take him...

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Ján ZEMAN (*1923)

“I don’t regret what happened. I regard all the things I did as my civic duty,” he said later. “Fourteen and a half years in jail at a young age was a major loss. But neither I nor my wife regretted it. I’m sad today. I was born in Czechoslovakia and I’ll die a Czechoslovak […]”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Vladislav ŽITŇÁK (*1932)

“Every day I was interrogated. My questioner was about six years older. It took four or five months and then we began speaking about all kinds of things. After five months I read what he’d written and began correcting the mistakes. Then he informed me there was a stool pigeon close to me. He told me not to talk tripe if I was with anybody in the cell…”

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Bohumil ZHOF (*1928)

“They put these boots on your feet when you were in your socks or bare feet. I don’t know exactly. They shoved them on me and when they turned on the current it felt like my feet would be ripped off. This was the first day and they didn’t even know what some of our names were. But they showed what they had on us. If you haven’t undergone it, you can’t comprehend it. The electric current was the worst. They had a transformer and turned the voltage up or down. They just said, Turn it up so he...

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)