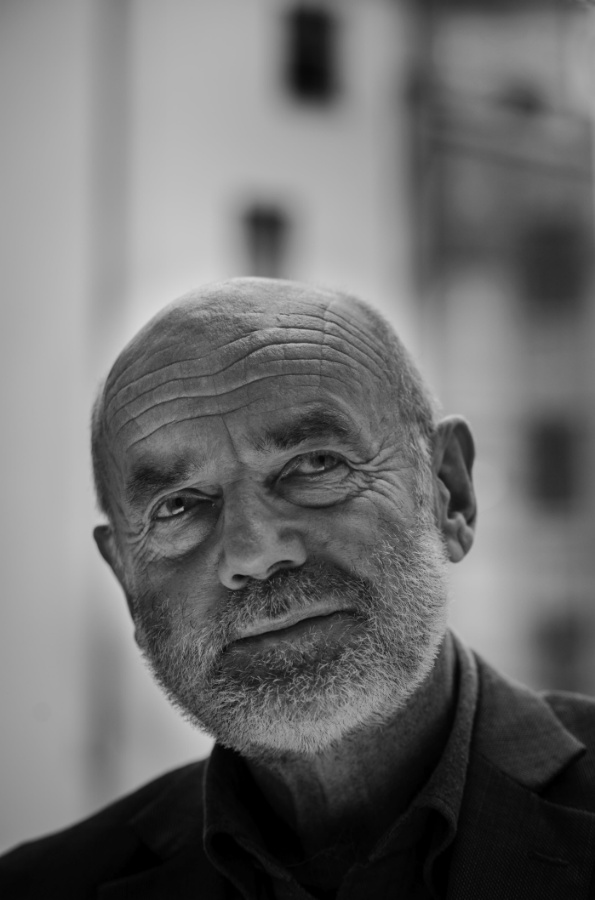

Jan RUML (*1953)

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

I was the child of parents who were rebels

Jan Ruml was born on 5 March 1953, the day of Stalin’s death. It was to be another 36 years before communism collapsed in Czechoslovakia. Jan Ruml is the son of Jiří Ruml, a Communist journalist who later turned against the regime, was jailed, signed Charter 77 and became editor-in-chief of samizdat newspaper Lidové noviny. His mother too had been a committed Communist. As a child Jan Ruml spent three years in Berlin, where his father was sent as a radio correspondent. His earliest memory dates from this period. “People on the eastern side of the border formed a mob and berated the soldiers building the Berlin Wall,” he says.

When Ruml was 15 his country was invaded by Warsaw Pact troops. “This event really united our family. Until my parents’ deaths we remained fast friends. My path was clearly set – I was the child of parents who were rebels.” Following the invasion his parents turned against the regime once and for all. There was no way Ruml himself would ever join the Socialist Youth Union. He graduated from secondary school in 1972 but the path to university was closed to him. “I tried around five universities but none of them would take me.”

In 1973 he began an apprenticeship as a film laboratory assistant at Barrandov, but six months later was forced to start earning a living operating furnaces at a gas station. He was surrounded by workers who knew he was there for political reasons. “They liked me. I learned in discussions how to speak to people, which later proved useful in politics.” After around two years he left to train as a bookseller at Melantrich.

Ruml remained at Melantrich until he signed Charter 77, when he was thrown out. “I left for South Bohemia and worked milking cows for a year.” In these days he became actively involved in the dissent. He regularly visited Prague and found work as a stoker, a job that spelled plenty of free time and was held by many dissidents. “I was constantly taking materials somewhere and duplicating texts.” Alongside Petr Uhl and Jiří Němec he built up an illegal distribution network, which naturally brought him into contact with opponents of communism throughout the country. He started helping publish the Spektrum magazine Infoch, had connections with Polish dissidents, helped distribute smuggled literature from the West and sent packages in the other direction. “I didn’t think up the text of Charter. I became the ‘legs’ of Charter, keeping it running. I organised hiding places, meetings…”

When at the end of the 1970s the regime locked up 10 representatives of the Committee for the Defence of the Unjustly Prosecuted Jan Ruml put together a second wave of members. He and Jiřina Šiklová organised truck deliveries from the UK, around 15 in total. When the smuggling network was uncovered in 1981 Ruml and a number of other dissidents ended up in investigative custody for a year. “They charged me with subversion. At first I found imprisonment quite tough, as Rudolf Battěk had received seven years. I expected a similar sentence.” Ruml, who refused to testify during interrogations, soon discovered his father had also been arrested. Fortunately they were all released in spring 1982. He continued his underground activities, working in a boiler room in winter and herding cows in the Slovak mountains in summer. “It was very romantic. We rode horses around the herd. Other dissidents visited us to get some rest.”

On several occasions Ruml took part in meetings with representatives of Poland’s Solidarity on the country’s border with Czechoslovakia. He was repeatedly detained for 48 hours. When the newspaper Lidové noviny started coming out in samizdat under the leadership of his father Jiří in 1987, he wrote for it occasionally, as well as playing a role in production and distribution.

When the Communist regime began collapsing following a demonstration on 17 November 1989, Jan Ruml was immediately at the centre of events. “The very next day we and people who were in charge of samizdat set up an independent press centre and moved to the U Řečických gallery.” From the start he was part of the narrow leadership surrounding Václav Havel. At this time he also took part in the first negotiations between Civic Forum and the Communist government, represented by federal prime minister Adamec. “When I came home I got a slap from my girlfriend for betraying the revolution. Those talks were my first political compromise.”

Not long afterwards part of the editorial team of the independent press centre hived off and established the magazine Respekt, with Ruml becoming its first editor-in-chief. Occupied as a journalist, he found himself outside the process under which dissidents took positions of power. But not for long. In view of his activities and firm anti-Communist position in the totalitarian period he received an offer from Václav Havel to join the Federal Ministry of the Interior in spring of 1990. In April, as a deputy minister, he found himself at the centre of the authority that had persecuted him for years. “When, dressed in jeans, I arrived at meetings with my subordinates they all stood to attention. It was most unpleasant. There was a military regime in place there.” Ruml was tasked with creating a new intelligence service and in the end was forced to throw out everybody who had held a leadership position in the old regime. He gradually set up a new police structure and also oversaw the prevention of StB collaborators entering high state posts. He ended up spending a total of seven years at the Interior Ministry, later of the Czech Republic, and played a very important role in the dismantling and transformation of the Communist regime’s units of repression.

Jan Ruml spent 15 years in high politics. He became government commissioner for refugee affairs and when the Civic Democratic Party was set up in 1991 he left Civic Forum. He remained in the Federal Assembly until the dissolution of Czechoslovakia at the end of 1992 and then became minister of the interior of the Czech Republic. In 1996 he was elected to the Chamber of Deputies on the Civic Democrats’ ticket. He quit the government in 1997 and later left the party. In January 1998 he co-founded the centre-right Freedom Union and became its first chairman. He stood down in 2000. From 1998 to 2004 he was a member of the Senate, serving as deputy speaker for the last four years of his term. From 1999 to 2004 he gained a degree at the Faculty of Law in Pilsen. He quit the Freedom Union and was a member of the Green Party from 2010 to 2014. After leaving politics he worked in consultancy. In 2006 he became chairman of the board of trustees of Respekt and helped save the magazine. He has been CEO of holding company SECAR BOHEMIA since 2017. He is married and has two children.

Text by Jan Horník