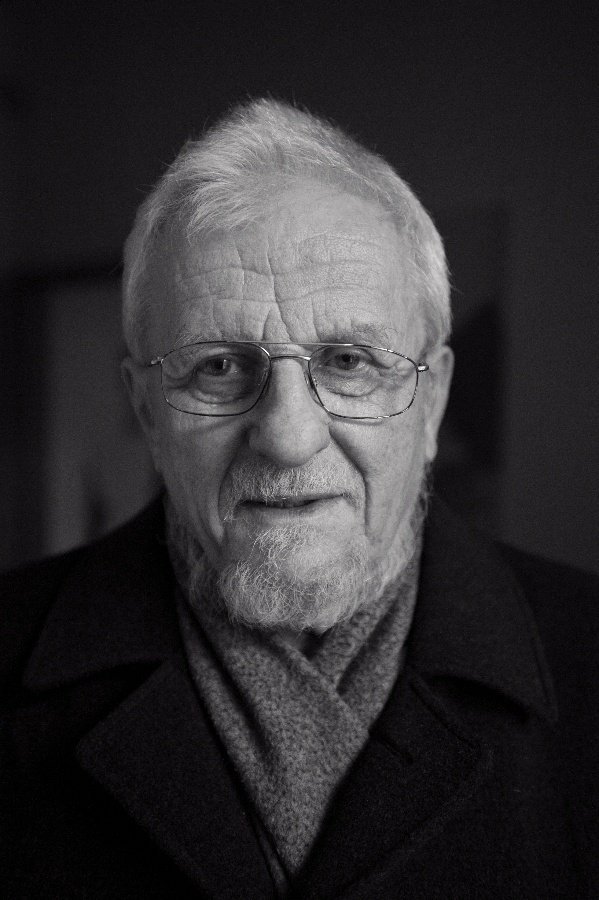

Bohumil DOLEŽAL (*1940)

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

We weren’t interested in “human rights for their own sake” but political engagement

Few in the Czech Republic today recall the Democratic Initiative (DI): a quarter century has passed since the fall of the Communist regime, there were many opposition groups in the last five years prior to November 1989 and most are only familiar with the best known of them, Charter 77. However, the Democratic Initiative differed from other groups in several respects. What’s more, their members were the first to apply to register as a political party at the Ministry of the Interior. They did so on 11 November 1989, so before the Communist Czechoslovak government began falling. Among the key figures in the DI was the literary critic, political scientist and later politician Bohumil Doležal.

He was born in Prague on 17 January 1940 into a “middle-class, not particularly wealthy blue-collar family”. He studied Czech and German as well as literature at Charles University’s Faculty of Arts (1957–1962) and later worked as an editor at the literary and academic section of the Čs. spisovatel publishing house (1962–1968). From 1964 he wrote freelance for the Tvář review, whose editorial team he later joined.

No periodicals were allowed to come out freely in Communist Czechoslovakia and Tvář was no exception. It was set up in 1964 by the Czechoslovak Writers’ Union (like all such institutions, supervised by the Central Committee of the Communist Party) as a platform for the young generation of official authors. However, the magazine soon became home to a group of distinctive, independent intellectuals, among them historian Emanuel Mandler, psychologist and philosopher Jiří Němec, philosopher Ladislav Hejdánek, literary critic Jan Lopatka, poet and historian Zbyněk Hejda, Russian Studies specialist Karel Štindl and poet and film critic Andrej Stankovič. Jan Nedvěd became editor-in-chief. The Tvářists attempted to return to cultural consciousness foreign and domestic writers suppressed for political reasons. They became heavily involved in a struggle against the censors and were marked by uncompromising criticism of the literature of the day, insisting that quality rather than ideology or ties of friendship should be a work’s sole criterion. Tvář was the only non-Marxist periodical and its openly critical approach was scarcely believable in the context of the arts scene of its day.

Doležal was one of the most distinctive writers. His area was poetry: “Jan Lopatka and I wrote that the whole of official literature post-1948 was a Potemkin village, that it was a simulation of literature and, what’s more, was ideologically trussed. (…) Though I was far from the most important person – that was Mandler, and then people who were far better educated and had better orientation than us, meaning Němec and Hejdánek – I was the direct cause of a quick kerfuffle. First I wrote that the chairman of the writer’s union, Jiří Šotola, wrote mishmashes and the same about Karel Šiktanc, who was also quite engaged, and it sparked a major scandal.” Tvář broke with custom and evaded the control of the authorities. It soon came into conflict with the Writers’ Union (and naturally with the party’s Central Committee) and the conflict escalated. Several major writers aligned themselves with Tvář (including dramatist Václav Havel) and the editors made brave efforts to save the magazine. However, it was shut down by an administrative step of the Writer’s Union in 1965. The editorial team remained in regular, friendly contact. In 1966–1967 Doležal edited the Tvář-style literary anthologies Forms 1 (Čs. spisovatel, 1967) and Forms II (not published until 1969; Václav Havel was listed as an editor for tactical reasons) and published pieces about poetry in various Czech and Slovak literary magazines (Literární noviny, Host do domu, Mladá tvorba, Slovenské pohľady). Tvář was successfully revived during the political thaw of 1968: “We could half operate publicly and publish normally in the period when Tvář was banned, but you still didn’t know what would happen if things got worse again. The entirety of the much praised Prague Spring was linked to terrible anticipation as to when would we see an invasion by the Russians, who eventually did invade. Even in the period when life was relatively at its best in Czechoslovakia, it was clear it wouldn’t end well.”

On the day of the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, 21 August 1968, Doležal was at a conference in Austria. He decided to return immediately and with the other Tvářists put out a leaflet magazine Slova svobody (Words of Freedom) in the first week of the occupation. He then worked as a critic and editor at the revived review until the normalisation Communist authorities again banned it, this time for good, in 1969. The Communist Party launched massive personnel purges in the arts sector and Doležal decided not to make undignified concessions. With a number of friends from the editorial team, he found manual work, first as a fitter and later was a technical worker at the Universa and Union Hostivice cooperatives: “After the banning of Tvář, Mandler, Nedvěd, Štindl and I decided not to wait for them to kick us out of the publishing house. We gave notice ourselves by 1 October 1969 and joined a production cooperative. There they said we could carry out production that we ran ourselves. So we produced plastic toys until 1974, then they threw us all out.”

From 1974 to 1989 Doležal made a living in other “alternative” jobs as a programmer and programming language instructor. In the first decade of normalisation he took part in two unsuccessful attempts to bring out Tvář in samizdat and decided to cease focusing on literature professionally. “When we entered the factory I lost contact with literature. I didn’t have any time for it. Later it struck me as nonsensical for me to return to literature in the situation surrounding and following Charter. I thought it was necessary to strive to bring about a more humane situation here, to which end, with all respect, poets would not suffice.” Bohumil Doležal signed Charter 77 in the “first wave”, immediately drawing increased State Security attention. “They searched my home, which I never understood, as I wasn’t linked to the nerve centre of Charter. I then deduced that it was perhaps because I had been insolent in an interrogation without realising it. Then it was calm for a while but in 1978 they suddenly picked me, drove me to a forest and beat me up a bit. (…) They did it the day after a similar attack on Ivan Medek.”

Though Bohumil Doležal was harassed because of Charter, he gradually became one if its opposition critics. In a nutshell, he reached the conclusion that Charter 77, based in its declaration on a call to uphold human rights (which Czechoslovakia’s representatives had formally signed up to in international accords) did not offer the country’s population a worthwhile alternative. Doležal regarded Charter’s strategy as unrealistic: the Communist regime was built on the suppression of rights and couldn’t be expected to start to adhere to them on the basis of civic calls as this would spell its own destruction. In Doležal’s view, the strategy hadn’t been thought through politically either: the Charter could not appeal to a large number of people because the abstract concept of human rights was too far-removed from their everyday concerns: “In those days Mandler even claimed that Charter made the situation in the country worse. I’d prefer to maintain a certain sobriety in this regard. I don’t know. One thing that must be set before all criticism of the Charter is that the impetus for it was the utterly cynical behaviour of the Bolshevik Czechoslovak authorities of the time, who accepted legal norms that they knew in advance they would not adhere to, or could not adhere to, and reckoned on nobody having the courage to stand up against this. That was outrageous brazenness and it wasn’t possible not to speak up against it. From this perspective, the Charter was legitimate.”

From 1979 to 1987 Bohumil Doležal wrote about Czech history and Czech political thought and was involved in the preparation of samizdat anthologies compiling the political articles and essays of Karel Havlíček Borovský, František Palacký and T.G. Masaryk. In 1987–1989 he was active alongside Mandler, Štindl and others in the aforementioned opposition political grouping Democratic Initiative: “By contrast with the mainstream of the Czech dissent, we emphasised the necessity of reaching out to the Czech public with a programme that would take into account their needs and wishes while also leading to more humanised politics and a switch from an authoritarian state to democracy. We weren’t interested in ‘human rights for their own sake’ but political engagement. In autumn 1989 we worked to ensure that embryonic political parties would emerge from the main opposition groups and when this didn’t meet with agreement from our partners we ourselves applied prior to 17 November to register as a political party outside the National Front (an umbrella group for permitted organisations subordinate to the Communist Party – author’s note).”

From November 1989, when the DI was transformed into a party, Doležal served as deputy chairman. Shortly after the fall of the regime, in January 1990, he was co-opted into the Federal Parliament on behalf of Civic Forum, of which DI was part. He was re-elected as a parliamentary deputy in summer 1990, this time for the Liberal Democratic Party, which the DI had turned into in June. In 1992 he switched to the Civic Democratic Party, where he was chief advisor to Václav Klaus in 1992–1993. However, he decided to quit after concluding that the gap between his views and those of Klaus was unsustainable and that he could have only a marginal impact on a practical political party in the circumstances. When he went to leave the Civic Democrats he discovered he had already been expelled for not paying party dues. From 1993 to 2002 Bohumil Doležal lectured on Czech and Hungarian political thought at Charles University’s Faculty of Social Sciences while also working as an independent journalist and political commentator. He became one of the main critics of the post-1989 transformation and was deeply engaged in the issue of the post-war expulsion of the Germans. In 1995 he helped initiate a joint statement by Czech and Sudeten German intellectuals entitled Reconciliation 95. Since 2000 he has published the politics blog Events. He has published pieces on politics in Czech, Slovak, German, Polish and Hungarian newspapers and magazines and penned several books, including Unconventional Politics (Torst 1996), Events, Essays (Prostor 2004), Unsuffered Literature (Torst, 2007), Karel Havlíček: Portrait of a Journalist (Argo 2013) and Events (Revolver Revue, 2014). He received the Revolver Revue Prize for 2011 and in 2014 was bestowed with the 1 June Prize by the city of Pilsen. He is a two-time laureate of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Hungary and received the Gábor Bethlen Prize. He is one of the most distinctive commentators on Czech public life.

Text by Adam Drda