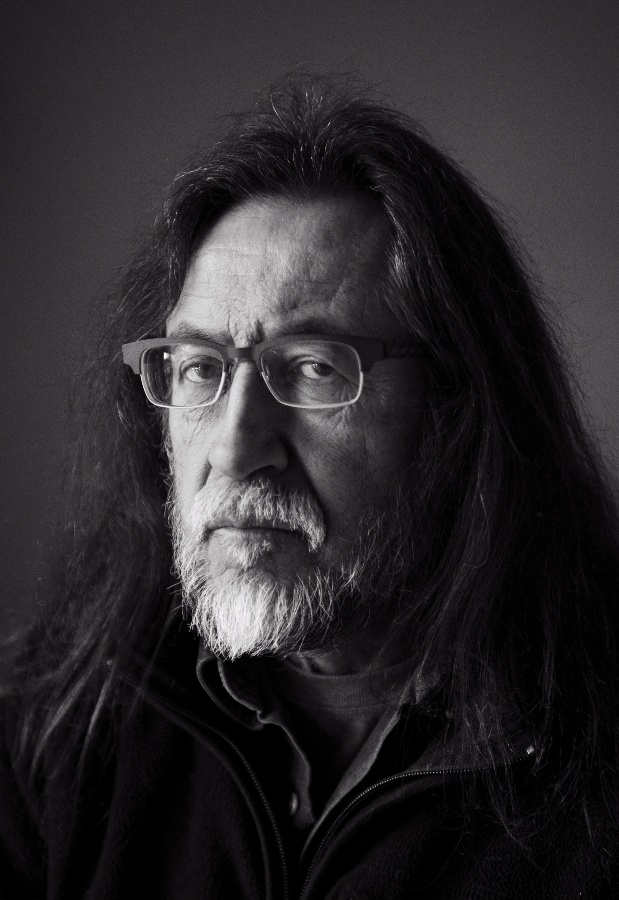

Karel "Kocour" HAVELKA (*1951)

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Twice an émigré

“It was 5:30 in the morning and I was at work and I was about to go to the building site. Suddenly the doors opened and in came two men in leather coats and hats. Like a scene out of a film. I immediately knew they were coming for me. ‘Mr. Havelka? – Come with us’. The two put me in the back of a car, between them, and we drove to Bory.” It was March 1976. Karel Havelka might have been wise not to return in 1974 from the US, which he had illegally left Czechoslovakia for a year earlier.

Karel Havelka was born on 12 July 1951 in Planá near Mariánské Lázně. He spent his childhood in Stříbřo, where his mother taught at an elementary school. His father was a site manager. Both parents had joined the Communist Party after the war in 1945. From a young age Havelka’s big hobby was music and he bought records and attended festivals. At 15 he began listening to the Beatles, who spoke to him deeply. He then started going to all kinds of concerts and festivals. In those days he had no idea he would one day be organising them in the underground. At secondary level he attended a construction-focused vocational school, opting for the transport construction field.

Following the invasion of August 1968 Havelka, then 18, began considering emigration. “The occupation was a shock to me. It was then that I first realised at a deep level that communism wasn’t some joke we were living through. But I didn’t want to escape without getting my school leaving exams.” He passed the exams in 1969. In April 1970 he entered two-year military service. After that he worked as a site manager.

At that time he reached a definite decision to emigrate. He and a friend looked into ways to cross the border. His friend Josef visited Čedok, where it was possible to book package tours of several days to the West. “‘All we have left is Japan,’ replied the girl at the counter. What’s more, we discovered that the tour cost 17,000 crowns, which was nearly the average yearly salary, and also that only Communist Party members and Union of Youth members were allowed to take part in the tour. We joined the Union of Youth so we could fulfil the condition.” They decided to buy tickets. In 1973 Karel Havelka sold all of his property. He arranged with his girlfriend that she would follow him to America, where he hoped to reach.

When they arrived in Japan they asked the US Embassy for asylum. They received it without a hitch and flew to the US. When Karel Havelka arrived in America all he had in his pockets was a few dollars. He worked where he could, finding jobs as a carpenter and loading trucks. He visited cities where blues was performed on the streets and went to concerts. However, his girlfriend didn’t manage to travel from Czechoslovakia, so after a year he decided to go back home. His arrival was smooth but when he reported after some time to the StB at the police in Pilsen he discovered he had been sentenced in the interim to 18 months for leaving the country. Incredibly, the StB believed his explanation that he was interested in American music and recommended he request a pardon from the president. “So I visited a lawyer who wrote me a pardon request and I sent it to the Office of the President. After around two months I actually got it! They completely dismissed my sentence.”

It was 1974. Havelka found work at a water structures company before later getting a job at an enterprise constructing roads and motorways. During 1975 he got to know people from the underground, including Ivan Martin “Magor” (“Madman”) Jirous, more closely. He got involved in staging concerts by unofficial bands and musicians. His final public event was a lecture on the underground by Magor in Přeštice, where other dissidents came to play music. The event ended when a midnight police raid. As an organiser, Havelka (who was known as Kocour, or Tom Cat) was arrested along with Magor, Čuňas and Skalák. They came for him at work early in the morning. “They accused us of disorderly conduct, but in fact it was a show trial. They did it that way so that in the eyes of the public we’d look like bad elements.” After an investigation lasting six months Havelka was sentenced in 1976 to 30 months. An appeals court reduced his sentence to 15 months.

Havelka was imprisoned at Bory in Pilsen. He was assigned the worst work there, polishing costume jewels. “I got a uniform with a green stripe, which meant I was regarded as a would-be escapee. So I never got outside the prison building, even to work. The first day I came to work I got a fright. They all had towels wrapped around their heads. There was terrible noise, steam and a stench from the vapours. It put me in mind of Dante’s Inferno.” He was given work applying putty and worked on the costume jewels for nine months.

Havelka learned about Charter 77 while still in prison. “In the canteen Zajíček leant toward me and said that 77 people had signed the Charter. Then I read Rudé právo and Švorc’s speech and it made me feel ill. I could completely see the yelling prosecutors and felt that I was actually in danger.” He later got a detailed account of the Charter from Skalák, who had already been released and was visiting the prison. A few days after being released in June 1977 Havelka signed Charter 77 at Dana Němcová’s place in Prague.

He again got work on the roads before later finding a job at Geofyzika. In 1978 he became co-owner of a building in Nová Víska, which he bought with 12 others from the underground. He kept living at Přeštice near Pilsen. At the end of the 1970s concerts involving numerous unofficial groups were held in Nová Víska. “There was virtually always an StB car in front of the building and they checked the papers of the people who came.” He and Čuňas expanded their samizdat activities and helped produce the magazine Vokno. When he ceased working at Geofyzika he was offered a site manager’s job completing a bridge at Švihov, where he hired a number of friends from the underground. “My condition was that I could choose my own people. We had a great group. There was just one old Communist among us. We wrote the Charter 77 symbol on one of the pillars of the bridge.”

However, at the turn of the 1970s and 1980s the police’s harassment and repression of the underground began to intensify. The StB made Havelka several “offers” to move. “There was one interrogation after which I decided to move away for the second time. This greying, elegantly dressed man came and yelled at me, threatening that they’d lock me up for espionage.” In view of the fact Havelka had escaped to the US in 1973 he took the threat seriously. He and his wife decided to leave for Austria. In November 1980 they moved to Vienna and applied for asylum.

In Austria he took casual work and traded in émigré literature, books and music. He opened a small second-hand record shop and smuggled music into Czechoslovakia. After the November 1989 Velvet Revolution he returned to his homeland. In 1990 he set up the music company Globus International. He put on concerts, promoting bands from the underground and the West, including among others Frank Zappa. Today he lives not far from Prague.

Text by Jan Horník