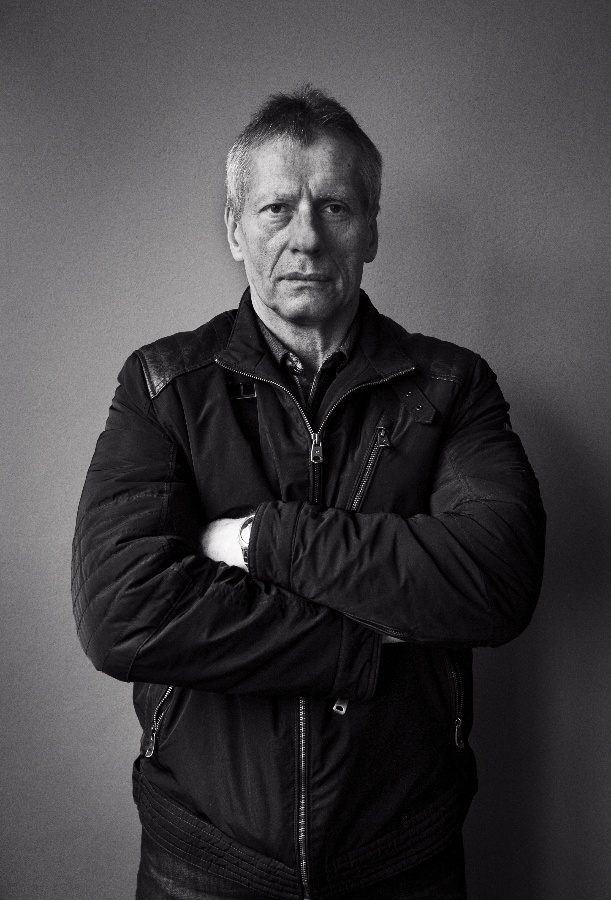

Vladimír HUČÍN (*1952)

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

We placed teargas canisters in dustbins…

Nobody can have stood up as unequivocally and stubbornly to the Communist regime in the 1970s and 1980s as Vladimír Hučín.

He was in fact conducting a private war: against the Czechoslovak Communists, the Soviet occupiers and their ideology. He stood out for the fact his resistance had the character of an armed struggle. Though he underwent harsh interrogations, they didn’t break him. “But the worst thing was that they broke my collaborator. He didn’t withstand the interrogations. I then wondered if I wasn’t to blame for not sufficiently preparing him in advance for the interrogations,” Hučín says.

As he was familiar with weapons and explosives, he decided to make use of his expertise: to destroy Communist symbols, glass-covered noticeboards bearing propaganda and banners celebrating the totalitarian regime.

He distributed leaflets with the slogan “Soviet dictatorship out”. This proved to be quite an effective method and the Communist authorities reacted very nervously. Hučín himself was surprised by how much effort the secret police began devoting to uncovering the culprits. This reassured him that his operations really were bothering the regime. So he continued. One of his operations was to disrupt celebrations of the Great October Socialist Revolution, the traditional public commemoration (generally an unstated duty) of the distant events in which the Russian Communists had come to power in 1917. In his memoir (Vladimír Hučín: Není to o mně, ale o nás/It’s Not About Me but About Us, Nuabia, Prague, September 2008) he describes how he disrupted those celebrations in Přerov, where he lived, in 1975. “Ahead of time Vlastimil Švéda and I placed five-kilogramme teargas canisters with timers in two dustbins. When they started to play the Internationale, smoke began to bellow out of the first bin. Unfortunately the second canister burned out. Its heat made the bin glow red hot and no smoke emerged. Just one teargas canister was sufficient for the whole event to be cancelled… The smoke blew over a military orchestra that was playing with enormous intensity. They tried to keep going,” Hučín wrote.

Later, in 1984, Hučín was convicted for distributing leaflets, possessing a weapon without a license and above all for organising an explosion at the home of StB agent Antonín Mikeš. He got two and a half years.

Vladimír Hučín was imprisoned in Minkovice, one of the toughest jails in Czechoslovakia. But he refused to yield. He didn’t hide his belief that his conviction had been political and received disciplinary punishments a total of 13 times. He spent the full two and a half years in jail. Following his release he was subject to protective judicial supervision for 18 months. Afterwards he was again in the secret police’s sights. Despite this, prior to the fall of communism he signed Charter 77, cooperated with Radio Free Europe and was a member of the Movement for Civic Freedom.

Vladimír Hučín was born in 1952 in Zlín, which at that time was named (after the first Communist president) Gottwaldov. Later in Přerov he did an apprenticeship as a mechanic at the company Meopta. He then attended Secondary Agricultural Technical School, which he did not complete. He worked as a labourer and had many different jobs. He was influenced by his father, who hid weapons during the war and was involved with the resistance. But the invasion by Soviet troops in August 1968 had the biggest impact on him. He was 16 and experienced that dramatic period most intensely.

He had his first personal conflict with the Communist authorities three years later. During celebrations of the 50th anniversary of the foundation of the Communist Party at a restaurant in Přerov he got into a heated dispute with drunken Communist functionaries. The dispute ended with the functionaries beating him up. But naturally he was the one punished. He was later convicted of the crime of disorderly conduct, had his passport confiscated and was expelled from secondary school. Later he was fired from his job for refusing to join the Socialist Youth Union and Socialist Work Brigades.

So he threw his energy into resistance, beginning with leaflets that read “Soviet dictatorship out”. But soon he moved on to explosives. There was a huge banner in the grounds of the Přerov Machine Works bearing the slogan “With the Soviet Union forever and always”. The banner was 25 metres long! On the anniversary of the Soviet occupation, on 21 August 1973, he blew it up with explosives.

At the same time Hučín began attacking glass-covered noticeboards that housed propaganda articles and slogans. “As soon as we started to attack them and successfully destroyed eight noticeboards, they started to make the cases at the apprentices centre at the Přerov Machine Works from metal. They were very sturdy, which then forced me to produce ever stronger explosives that would be capable of destroying these metal products propagating the Communist Party.”

However, it was then that the StB got on to Hučín’s trail. In October 1976 he ended up in custody. But they found nothing during a home search. Just a pistol that was an historical weapon and incapable of shooting. However, Hučín’s collaborators, Vlastimil Švéda and Miloslav Jemelka, were also interrogated. The secret police received information on Hučín from Antonín Mikeš, whom they had recruited as a secret collaborator and later agent.

The court sentenced Hučín for illegal possession of a weapon but he got away with a conditional sentence. He was helped by his resilience – he admitted nothing. His careful concealment off all possible evidence also proved beneficial. Though the secret police were suspicious he continued in his resistance activities. For instance, he planned to take action during the unveiling of a new statue of Gottwald, though the attack never went ahead. In addition that year he was called in for questioning on the anniversary of the Soviet occupation: 21 August. Evidently as a precaution, to make sure he couldn’t carry anything out on that day.

But Hučín had already planned his next move. In December 1983 he set off an explosion at the home of Mikeš. The next day he was arrested. He was convicted soon afterwards. It was a long list of charges: alongside organising and explosion the crime of incitement, the illegal possession of weapons and, some time after the event, the circulation of anti-Soviet leaflets. He got two and a half years and had to serve the full term. “I was assigned to a section where they polished pieces of glass that were used to make crystal products, such as chandeliers. It was back-breaking work. At the very beginning the large grinding stones rubbed off my upper palms and fingertips,” he said. Vladimír Hučín emerged from prison in June 1986 but remained in the sights of the secret police. First he was subject to so-called protective judicial supervision and later kept under surveillance. On 21 August 1989 the police removed him from his place of work for a so-called submission of explanation. Evidently intending to intimidate him, they held him all day – probably to ensure he couldn’t carry out anything on the anniversary of the occupation. But Hučín refused to be intimidated. He declared that he had signed Charter 77 and told the StB officers they would be surprised if they knew how many people had come to him to sign the “Several Sentences” petition. Immediately after the interrogation he called Radio Free Europe, outside the Iron Curtain, with news of his detention.

After the fall of the Communist regime Vladimír Hučín faced severe criticism and was involved in numerous disputes. But that’s another story. On 28 April 2014 he received a certificate attesting to his participation in the resistance and opposition to communism from the Czech Ministry of Defence.

Text by Luděk Navara