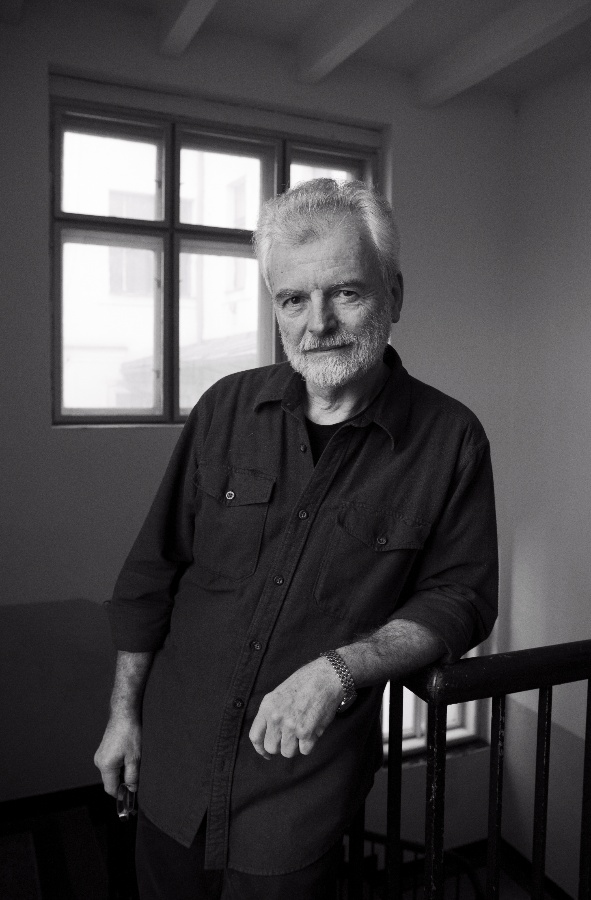

Čestmír HUŇÁT (*1950)

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Organiser, promoter, official...

Čestmír Huňát is a major music fan and a significant part of his life has been connected to the art form. However, he doesn’t play an instrument and says he lacked the necessary talent and perseverance in his youth: “I didn’t excel in other disciplines either, even though I liked them. And in the end I became an organiser, a promoter – basically a kind of alternative official.” He has been so since 1975, when he began to fully devote his energies to alternative culture as an activist with the Czechoslovak Union of Musicians’ Jazz Section.

Čestmír Huňát was born on 31 October 1950 as the only child of diplomat Josef Huňát and dressmaker Jiřina Huňátová. This was less than three years after the Communist takeover. His dad forged a career in the new regime and at the start of the 1950s took up a posting in the Netherlands with his wife. Čestmír was with his parents there for a while, though he began attending school in Prague. After some time his father got a new posting so the son (again only briefly) enrolled in school in Burma, South Asia. From 1966 to 1969 he attended the grammar school named, after the street, “Velvarská, later Leninova and today Evropská”. It was a formative time for him as he experienced liberalisation (linked to the 1968 Prague Spring), feeling it most keenly in the arts, particularly music: “Suddenly we had the feeling that we had an overview of everything, that we were ‘going places’ in music the same way the Americans and English were. Music clubs were appearing. Lots of groups started… We felt that we had a chance to get involved.” The Soviet occupation ended that brief period of relative freedom on 21 August 1968. Čestmír Huňát, like most of his peers, took the blow hard. However, what was worse was the frustration of subsequent years, when the collaborationist leaders of the Communist Party began reintroducing a hard-line regime in the country. “For me it was far worse when I watched people ‘turning’, how they changed their outlooks. Not just politicians, but our professors at school, the director.” At the start of so-called normalisation he enrolled at the Czech Technical University’s Faculty of Construction. His father, a reform Communist, fell victim to the party purges and tragically died in 1971 after collapsing at the wheel of his car.

In those days Čestmír sought an escape from the expanding Bolshevik cultural desert. The bands he wanted to listen to were barred from playing and no books worth reading were published. Anybody who had “breathed freedom” suffered from the lack of oxygen in the grey of normalisation – and in Huňát’s case this state continued until 1975. “I was looking for a job. I got into the enterprise Metroprojekt and friends (…) told me that Vladimír Kouřil, who also worked at the Jazz Section, was employed there – and that I should meet him. I mumbled something about jazz not doing much for me but one thing led to another – and in 1976 I was an activist at the section. It became the fabric of my life and, alongside my family, was the only thing that gave my being in Czechoslovakia any meaning.”

This is not the place to present the complicated history of the Jazz Section (JS). But in brief, it was born at the turn of the 1960s and 1970s and was an amateur association that fell under the nationwide Union of Musicians. However, from the start it had its own structure, legal authority and financial management. Its leadership contained no Communist Party members, which was to prove important. The JS began to issue the bulletin Jazz (and gradually books, as part of the Jazzpetit series) and alongside other activities organised the Prague Jazz Days festival in 1974. In the mid-1970s the JS’s deputy chairman, Karel Srp, decided to organise a jazz rock workshop. More or less from that point on the JS focused not only on jazz and jazz rock but also the alternative rock that the regime rejected and persecuted. Hundreds of sympathisers and would-be members, who sensed in the JS a somewhat open cultural space, began signing up. In 1976 JS secretary Vladimír Kouřil wrote about the turning point in what had previously been a purely jazz focus. “From then on, shows of rock amateurs became the most important event in the development of the Jazz Section.”

The JS’s activities continued to diversify and Čestmír Huňát, by then a construction engineer, had long been one of its “activists”. What did it involve? “At least once a week (…) we had visiting hours at a small house in Kačerov (…) and people travelled there for information and various materials. With friends, we put together the entire agenda, from transporting printed materials to administration to preparing jazz festivals and concerts. We gradually organised exhibitions and travelled outside Prague to various gatherings. We conducted a systemic war with the regime.”

The Communist authorities’ antipathy to the JS grew. They did all they could to make things hard for the JS but it was over a decade before they managed to eliminate it. Through various far-sighted moves the JS made it harder for the regime to come down on it. For instance, in 1978 it became a member of the International Jazz Federation (part of UNESCO), which meant any clampdown would have international repercussions. Čestmír Huňát emphasises that the JS “persistently sought to function legally. In that way it differed from the underground. We concluded that, given that we had one opportunity, we would make the most of it if we remained within the ‘regular’ structures and took advantages of the weaknesses in the regime’s regulations. For a long time we succeeded.”

In September 1980 the Jazz Section was abolished. The decision was taken by the Central Committee of the Union of Musicians under pressure from senior Communist Party bodies. The JS defended itself, disputing the decision. In June 1981 Karel Srp became chairman. The same year the Prague Jazz Days were banned. From then on the JS chiefly focused on publishing – it put out the Jazz bulletin, fine arts monographs, literature, etc. In Čestmír Huňát’s words “the Jazz Section essentially escaped from regime control. We published books that weren’t subject to censorship. It was the same with concerts, at which new wave bands who weren’t allowed to make a living from music appeared. The membership base comprised a dense network of active people, which the State Security didn’t take too kindly to (…) Our ever-growing international cooperation also annoyed them.” An StB document on the JS from July 1985 reads: “Numerous measures have been taken to limit the negative activities of the Jazz Section (…). In view of the inability of the Union of Musicians to resolve the situation, despite several warnings, the activities of the Union of Musicians were halted and on 22. 10. 1984, under a Ministry of the Interior decision, (…) the organisation was dissolved.” Once the Union of Musicians had been wiped out, the regime regarded the Jazz Section as also abolished. However, its representatives refused to accept this.

In 1986 Čestmír Huňát was a member of the JS committee: “Sometime at the start of September, the StB rang the bell at our place before 6 in the morning (…) they carried out a home search – and confiscated everything connected to the Section (…) A search at work followed (…). Then they took me to Ruzyně prison.”

The StB arrested the entire JS leadership at this time: “We were all prepared for them coming for us one day. We were aware of the risk. But we didn’t expect that it would affect so many people (…). Custody was most unpleasant. But as you knew what you were there for, and that you were right, it was possible to bear it.”

All of those arrested were to be convicted in a trumped-up trial for tax evasion. The StB didn’t dare put on a pure show trial. The charges pertained to several million crowns. However, it soon transpired that the structure of the indictment wouldn’t hold up, so the prosecutor employed different articles, in particular against those accused of unauthorised business activities. “It came down to ambiguities surrounding 36,000 crowns, which of course we hadn’t stolen but invested in the Section. So the judge had to state that our activities were to the good – they just weren’t in accordance with the regulations.”

In January 1987 Čestmír Huňát was (like several others who had been arrested) released from custody. The trial took place in March and crowds turned up at the court to support the accused. From the international political perspective the trial was a disaster. Petitions were created in the West and there were open letters and articles in support of the JS. Kurt Vonnegut, John Updike, E. L. Doctorow, Wynton Marsalis, Arthur Miller, William Styron and Sonny Rollins protested to varying degrees. A petition by UK musicians sent to Czechoslovak president Gustáv Husák was signed by the likes of Paul McCartney, Sting and Andrew Lloyd Webber. Nevertheless, several JS people were convicted. Among them was Čestmír Huňát, who got a suspended eight-month sentence.

While the leadership of the formally dissolved Jazz Section were still in custody a Working Committee was established to drum up support for the accused and keep the JS alive. As soon as he was released, Čestmír Huňát got involved in those activities: “Even in court we tried to revive the activities of the paralysed Section. We had around 8,000 registered members and we wanted to give them a shot in the arm, to show we hadn’t disappeared. In 1987 we chose the name Unijazz – and created a successor organisation on the old foundations that we wished to have made legal.”

Following Karel Srp’s return from prison there was discord among the original members with regard to direction. Srp left Unijazz and soon started his own organisation, Artforum. For Čestmír Huňát it was also a tough time personally. He was on probation and following his release came under the most intense pressure yet from the StB. Secret policemen started coming to his place of work and began trying to force him to become an informer. “They simultaneously pressured and discredited me. (…) They wanted me to sign on to cooperate. (…). I didn’t sign and they weren’t too pleased. And they kept hassling me and spied on me incessantly.” Rumours soon spread that Huňát was an StB collaborator. “The police put that about deliberately. I don’t know all the channels, but unfortunately it was also through people I had trusted up to then. (…). Unfortunately, whether knowingly or not, Karel Srp, whom the JS members trusted completely, also contributed to the circulation of this falsehood. I took it hard. There was no defence against it.” Unijazz didn’t acquire registration under communism. Srp’s Artforum did.

In November 1989 Čestmír Huňát took part in a demonstration against the regime on Národní třída. “I was beaten and ended up with my arm in plaster.” In the weeks that followed the Communist regime collapsed and after a brief engagement in Civic Forum Huňát returned to the arts. Unijazz, now allowed to work freely, began organising festivals and brought out a magazine. With time it was possible to prove that suspicions Huňát had collaborated with the StB were wholly untrue. But another Jazz Section member was registered from 1982 as an StB agent: Karel Srp.

Unijazz, of which Čestmír Huňát is chairman, is today one of the few independent initiatives that emerged before the revolution and has survived to this day in a scarcely replaceable form. The association runs a popular Prague café and arts centre and has organised a festival in the Jewish quarter in Boskovice since 1993. That same year it also launched the international festival Alternativa, one of this country’s most important showcases of alternative and experimental music.

Text by Adam Drda