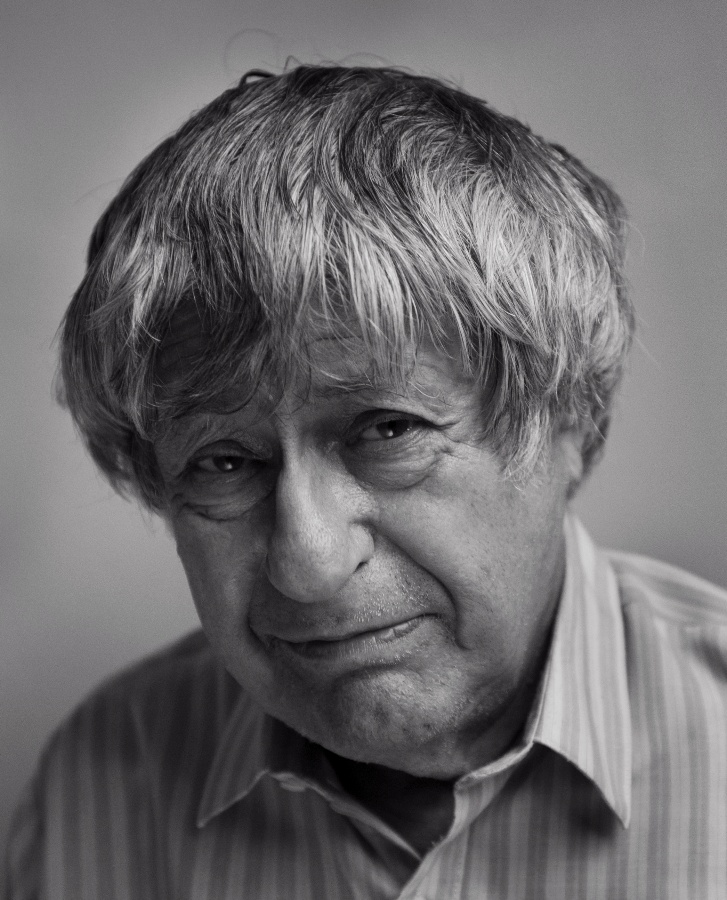

Ivan KLÍMA (*1931)

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Everybody thought more than they could officially write

The novelist and playwright Ivan Klíma was born on 14 September 1931 into a Prague Jewish family. His father Vilém worked at the Kolben plant in Vysočany as an electrical engineer. His mother Marta, who spoke five languages, was a secretary. He had a brother seven years younger. The family were not religious Jews. “Czech was the only language spoken at home. Mum was a patriot. We never practiced the faith.”

However, once the threat posed by Hitler’s regime became clear, the father found work at a factory in Liverpool and tried to get visas for the rest of the family. As his own mother was still waiting on a visa, however, he decided to postpone the departure for England. But this led to the whole family missing the window of opportunity to leave. “On the first day of the occupation, 15 March, the Gestapo came to our place, as my mother’s brothers were members of the central committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. They didn’t find them at our place, but on the very first day I learned what the Gestapo was.” Soon Ivan was faced with all manner of anti-Jewish bans. He couldn’t go to school, go to the cinema, etc. “But the neighbours behaved normally toward us. A total of three Jewish families lived in our apartment building.”

In November 1941, when Ivan was 10 years old, his father was summoned to the first ever transport to Terezín. “We had two hours to pack. Mum collapsed and neighbours helped us to pack. We stayed for one night at the Trade Fair Palace in Holešovice.” Ivan and his mother were placed in a barracks in Dresden. His father headed a gang of electricians and lived separately. Thanks to his father’s job, in time the family were able to move into a shared room at the Magdeburg barracks. “We even had a wardrobe and a chair. A chair was a big thing. We placed a basin on it and we also had a bucket. We even owned a plate. Huge comfort, simply.”

His father’s position as an electrician saved the whole family from transports to the death camps. As a specialist at the end of the war he was also sent to the labour camps, but he survived the war and when it was over returned to Terezín on a death march. There all of them – Ivan, his mother, brother and grandmother – were liberated. However, most relatives from Klíma’s broader family had been murdered in the Holocaust.

Klíma returned to Prague after the war. He was 14. While in Terezín he had written a few sketches. His talent as a writer began to make itself felt. He entered third year at grammar school, which he graduated from in 1951. “There I fell in love with a fellow student and began writing romantic novels. I’ve still got one notebook, though it’s awfully frothy. But it was my first extensive writing.”

The Communist putsch of February 1948 was regarded positively by Klíma’s family. His father was a member of the Communist Party and his uncles had been executed as Communists during the war. However, Ivan was more Trotskyist in outlook and was cool on Stalinism. In 1953 he joined the Communist Party. Paradoxically it was then that his father was arrested by the Communists and later sentenced to 18 months in a show trial. “When father returned he revealed a lot to us about the regime. But he remained in the Communist Party in an effort to reform the regime.” Ivan himself was also unable to break free of the ideology at that time and remained in the party.

In the years 1952 to 1956 he studied philology at Charles University’s Faculty of Arts. At that time such renowned names as Mukařovský were still lecturing there. “Given what went on in the 1950s, it still wasn’t a complete waste of time.” Until the mid-1950s Klíma was active in an Evangelical choir. From 1956 he worked as an editor with the magazine Květy. He got married in 1958.

When Khrushchev revealed Stalin’s crimes in 1956 Klíma realised once and for all that communism was a criminal regime. “I remained in the party, as there was no other way reforming it. In the 1960s you could write very critically, but if you were not a party member you were still a poor devil.” From 1963 he was for three years editor-in-chief of Literární noviny. “There we were able to speak about the regime among ourselves completely openly. Nobody informed on anybody. Everybody thought more than they could officially write. But some things did work out.”

Klíma’s gradual emancipation from the ideology of communism reached a climax at the Fourth Congress of the Union of Czechoslovak Writers, when alongside other members he called for the cessation of censorship. However, that proved too much for Dubček’s reform-minded regime and he was expelled from the Communist Party in 1967. That same year Klíma was offered the position of visiting professor at the University of Michigan in the US city of Ann Arbor, where he had been invited to the premiere of his play The Castle. “I later received an official invitation and went.” Meanwhile, the Communist Party overturned his expulsion in 1968.

When Warsaw Pact forces occupied Czechoslovakia in August 1968 Klíma was in London. “It was a shock to me. Later when Husák came to power we were all ordered to return from trips abroad. We could also have emigrated.” Despite efforts to persuade him to stay, Klíma and his wife Helena decided to go home. Following their return from the US he became a banned author and was unable to publish publicly. In 1970 he was stripped of his passport. His books vanished from counters and bookshelves. He was definitively expelled from the Communist Party. However, his books could still come out abroad and as he received royalties he could make a living as a writer. “The publisher sent me foreign currency. I changed it for vouchers at the bank and sold them. After a while I was even able to get a car.”

In the normalisation period Klíma organised meetings of banned writers at his apartment. “Trefulka and Uhde used to come from Brno, Šimečka from Slovakia and Kliment, Sidon, Vaculík, Pecka and others from Prague.” He helped smuggle samizdat via the German Embassy and began publishing the underground monthly Obsah. Initially he occasionally had to take a labouring job for insurance purposes but he later got a contract with Krátký film, where he could forget about side jobs and completely concentrate on his art.

His activities in the circle of banned writers did not, of course, escape the StB, so he toned down the large gatherings. From time to time the STB called Klíma in for questioning, although he was never imprisoned. Only his wife Helena signed Charter 77 as Klíma didn’t want to endanger his illegal contacts with foreign countries. Today he views his party membership critically. “I was a member of a criminal organisation, without having committed any crime myself. But of course due to my membership I did bear a certain responsibility. I knew that’d I’d have to make up for that until my death.”

Following 1989’s Velvet Revolution Klíma’s banned books began coming out, in runs exceeding hundreds of thousands of copies. From 1989 to 1993 he was chairman of the Czech PEN club. Ivan Klíma is the author of countless short stories, essays and novels, such as An Hour of Silence (1963) and Love and Garbage (1987). He has also produced plays, including The Castle (1964), the one-act piece Sweetshop Miriam (1968), A Groom for Marcela (1969), A Room for Two (1973) and a stage adaption of Franz Kafka’s America, which he wrote with Pavel Kohout.

In 2002 he received the Franz Kafka Prize while in 2010 he got the Czech literary award Magnesia Litera. He is one of the most translated living Czech authors. He lives in Prague.

Text by Jan Horník