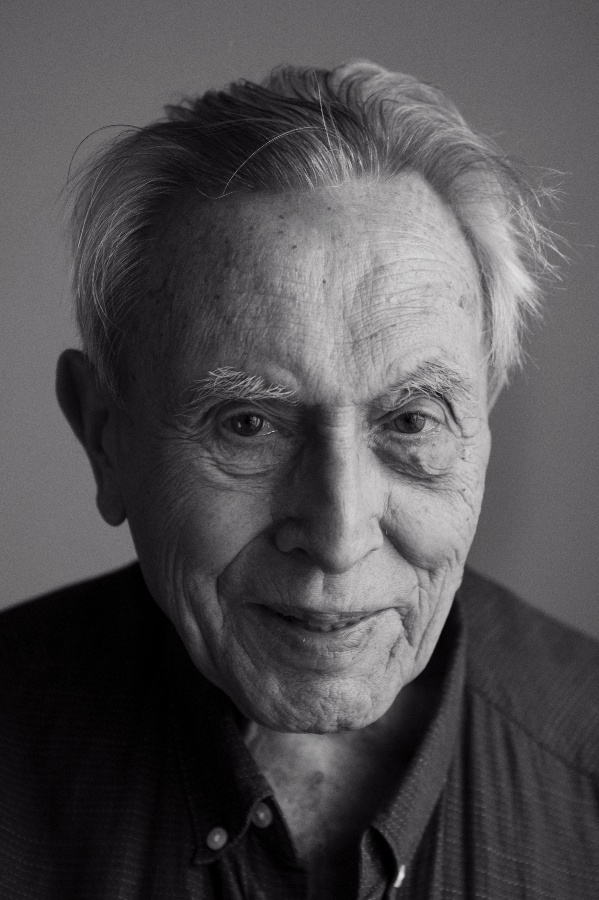

Felix KOLMER (*1922)

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

I promised I’d come back

The young Jewish man Felix Kolmer celebrated his 22nd birthday as a prisoner in Terezín (Theresienstadt). He was in those days part of a resistance organisation and was tasked with finding an escape route out of the Terezín ghetto. He succeeded: “We knew that underneath Terezín there was an entire system of corridors, built at the same as the fortress in 1780. (…) After about six months of searching, I found a corridor. We wanted to use that way out if the SS started shooting us.” Kolmer didn’t escape from the ghetto, in part out of consideration for the others. “I had made an oath that I would find out where the way out was and, if it became necessary, would lead escaping prisoners there.”

Felix Kolmer was born on 3 May 1922 into a Jewish family in Prague’s Vinohrady district. His father (a one-time Italian legionnaire) was an electrical engineer. He worked for the company Eta before later opening his own electrical goods shop. He died when Felix was 10 and Mrs. Kolmerová was after a while forced to close the store. At that time Felix had a guardian, an uncle living in Austria. This meant he usually spent the holidays and Christmas in Vienna or the Alps. After the Anschluss his relatives fled to the US.

The subsequent Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia (in March 1939) completely changed Felix Kolmer’s life. First his family lost their apartment due to anti-Semitic regulations and were forced to live with his grandmother, moving from Vinohrady to the Old Town. Felix was a keen scout but the Nazis banned scouting. He attended secondary school, graduating in June 1940. However, as Jews were barred from studying from September 1940 (alongside numerous other forms of persecution) he became an apprentice joiner. From September of the following year he was forced to wear a yellow star. The Protectorate authorities seized the remainder of the family’s property. Some friends no longer greeted Felix.

In November 1941 the Nazis created a ghetto at the Terezín military fortress that had numerous functions (as a model ghetto for propaganda purposes, an old-age ghetto and a concentration camp). Terezín contained Jews from the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, Germany, Austria and other countries and transports from the ghetto went further east, in particular to the Auschwitz and Treblinka death camps. Felix Kolmer was sent to Terezín on 24 November 1941, in the very first transport, as a member of the so-called Aufbaukommando, the “construction commando”. “It comprised 342 young guys from 18 to 22 years of age. Some older ones were also sent, to establish a Jewish leadership. Almost all of us young guys had some trade (…) We got summonses from the Prague Jewish Community saying we were to arrive at 5 in the morning at today’s Masaryk train station. We assembled there. Each of us had a rucksack and food for three days, as prescribed. We didn’t know where we were going. We thought it’d be a few days’ work and that then we’d return to Prague.”

In Terezín the young men, including Felix, were ordered to prepare the ghetto for the arrival of transports. They carried out all kinds of work, for the main part adapting the main building, originally a barracks. After some time Felix was placed in the section delivering foodstuffs around the ghetto from a central store. Two times a week he was brought to the nearby Terezín small fortress (at that time a Gestapo prison), where he worked as a joiner and carpenter. “The whole day an SS man was stood beside me, watching to make sure I didn’t come into contact with the prisoners. But what I saw was enough for me. Inhuman cruelty. I saw Jews with their hands broken who the SS were forcing to work using whips. Of course it was impossible, so the whipping continued until the person was beaten to death.” In December 1941 Felix’s grandmother and mother were sent to Terezín. The latter died within two days of encephalitis. The members of the first work transport were allowed to list on their personal cards close persons, who were temporarily protected from transports to the east. Alongside his mother and grandmother, Felix included on his the name of Liana Forgáčová, whom he had known from the age of four (and whom he married in the ghetto on 14 June 1944) and her mother. This helped Liana survive and they spent their whole lives together.

As mentioned, Felix Kolmer joined a resistance organisation in the ghetto. The resistance in Terezín had a specific form, corresponding to the harsh conditions. It was comprised of several groups (Zionists, Communists) that attempted to gather correct information on the development of the war and circulate it among prisoners, as well as helping those in grave danger. Though the members of the resistance had hardly any weapons they did prepare, for instance, for the possibility of an uprising that was to break out if the Nazis attempted to murder and shut down the entire ghetto. A friend, a resistance member, asked Kolmer to try to find an escape route. “He explained he had a secret mission for me and I agreed to it. (…) That friend was the head of our three-member group. We were organised in such small groups so the others wouldn’t know about us, so the Germans couldn’t beat anything out of us even if they caught us.” When Felix found the escape route from the ghetto he twice used it and secretly went beyond the ramparts. But he always returned. He knew that the route, which nobody else knew about, could serve all of the others if it came to it.

In the autumn of 1944 the final major transports from Terezín set off for the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp. Among the 1,500 or so unfortunates on them was Felix Kolmer. By a twist of fate he was not placed among those immediately murdered in the gas chamber but was put in a group assigned to work temporarily. “I remember the arrival well. The dawn began and on the ramp there were people in prisoners’ clothes. That was the first time I had seen such prisoners’ clothes. (…). A man approached me and said: ‘There’s no escape from here. The only way you’ll leave here is via that chimney.’ I thought he was off his rocker. I didn’t understand where I was. My brain just didn’t take it in. Later I saw that on one side, walking in rows of five, were children and old people. Those were people over 42. And I understood that they were clearly going to their deaths. But still the term gas chambers didn’t say anything to me.”

Felix Kolmer recalls that above the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp “there was light at night like in the day, from the flames licking out of five crematoriums. Throughout the camp there was a kind of cloying aroma, or actually a stench. The stench of burning human flesh. (…). We just had one thought there. To survive the next minute, the next hour, perhaps the next day. And, if we were very lucky, a week. We couldn’t think any further ahead.” Kolmer may well have been helped by his experience from the scouts, the ability and habit of looking after himself and also not putting himself first. Above all, he, like others who survived, was inexplicably lucky. He was selected for a commando of prisoners assigned for heavy work in a sulphur mine. When the commando’s members were being herded one night onto a ramp leading onto a train Kolmer spotted a former fellow inmate from Terezín, waiting for a transport. He managed to run across to him – and nobody noticed.

In this way he escaped to the Friedland labour camp (KC Gross Rosen section), where there was a slightly higher chance of survival. But naturally people also met their deaths there. Kolmer recalls suffering from such hunger than he and some others even ate the innards of dead horses dug out of the ground. At the start of May the approaching Red Army shot up a power station supplying electricity to the camp. When the lights went out around 200 (of a total of 600) prisoners escaped over the fence. Felix was among them. They reached the Soviet army and later Czech territory. During fighting at the train station in Choceň, in the daying days of the war, Kolmer almost lost his life. But he reached Prague, where he was happily reunited with his wife, who had returned from Terezín.

Influenced by his father, Felix Kolmer developed an interest in electrical engineering at a young age and had always wanted to become an electrical engineer. After the war he began attending courses and in the end enrolled at the Faculty of Mechanical and Electrical Engineering. He graduated in 1949 and found work at the Research Institute of Visual, Audio and Reproduction Technology. He became a scientist and from 1962 was a researcher and lecturer in physics and acoustics at the Faculty of Electrical Engineering, In 1982 he received a professorship and joined Prague’s FAMU film school, where he lectured to an advanced age. He became a world-renowned expert in acoustics.

Text by Adam Drda