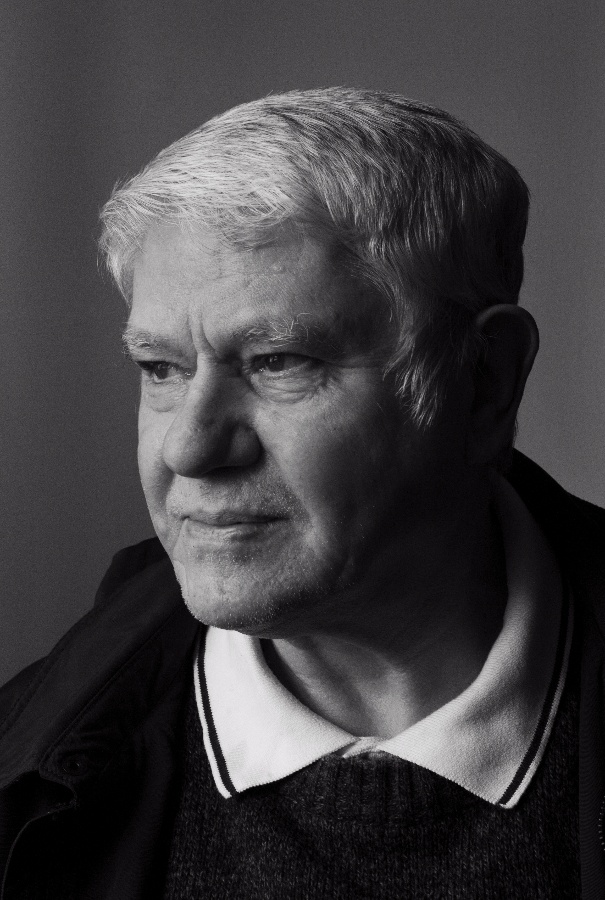

Václav MALÝ (*1950)

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Finding a way to clearly express my disagreement

On 25 November 1989 the Roman Catholic priest and dissident Václav Malý stood at the microphone on a tribune at Prague’s Letná Plain. The Communist regime had been collapsing for days and in front of, or rather beneath, Malý was a crowd of half a million demanding that collapse. Officers of the Public Security – whose riot units had just days earlier brutally broke up demonstrators in central Prague – also spoke, expressing a certain remorse. Father Malý then called on those gathered to join him in the Lord’s Prayer. It was a noteworthy moment. To that point the official ideology of Czechoslovakia had been Marxism-Leninism. Though admittedly nobody believed in that, nobody could have predicted that people would accept a Christian prayer after decades of enforced atheism.

“Naturally I wasn’t certain and I hesitated inside. In the end when I introduced those police officers, who had come to apologise, I said to myself: ‘I’ll risk it.’ And I wasn’t under any illusions, because as it turned out the majority of the people gathered didn’t even know the Lord’s Prayer. Nevertheless, it was touching that those people at least opened their mouths,” Malý recalled over 20 years later. “It was a risk but one that worked out. It was a surprise to many at the time. I think it was the best way to show that freedom had fallen into our laps and was more than anything a gift from God. That it wasn’t to the credit of individuals or of some movements, but that it was a combination of various circumstances within which I saw God’s guidance. That’s how I view it to this day, without mystifying or spiritualising it. However, I was taken aback by the objections of some I wouldn’t have expected it from. But those 40 years of pressure had also left their mark on those people, that caution. Some believed it was too much.”

Václav Malý was born in Prague on 21 September 1950 into a Christian family. He group up in period of harsh totalitarianism, omnipresent fear and large trials of Catholics. However, speech was open in the Malý household, even with the children: “We weren’t brought up in a home where parents placed their finger to their lips, saying we weren’t allowed to say this or that. We spoke completely openly with our parents about what was going on. Naturally when I went to school I didn’t broadcast everything I had heard. But also people who had been in prison used to visit us, so from the start it was clear to me what kind of system we were living in.” Thanks to his parents Václav Malý knew that it was possible even under a Communist regime to maintain face and a straight spine and that “when I’m convinced of something then it’s sometimes worth a blow or a victim. I later carried this into the rest of my life.”

In the 1960s Václav Malý attended grammar school at Prague’s Na Zatlance. Shortly after the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia he decided to become a priest. In 1969, at the inception of normalisation, he entered the Cyril and Methodius Faculty of Theology in Litoměřice: “My decision for the priesthood was partly shaped by the political and societal atmosphere, because I observed how from spring 1969 people again started to grimace, started to live two-faced lives, started to be afraid. (The occupation followed a brief liberalisation in Czechoslovakia in 1969 – author’s note). I said to myself that it was just impossible that somebody would keep changing their position on the basis of external circumstances. Either I’m convinced of something and adhere to it, or I change my opinions according to the majority direction. And because I was brought up religious and was a Christian my thoughts were thus: ‘Yes, I wish to be a priest to so that I can encourage people of the value of standing on firm spiritual foundations.’ To me this was gospel. I wanted to share it with others and to also show them the way.”

Václav Malý completed his studies in 1976. He faced the threat of not being ordained after criticising the collaborationist organisation Pacem in Terris, however he became a priest on the intercession of Cardinal František Tomášek and was then eligible to serve as a chaplain in Vlašim and Plzeň.

When Charter 77 was published in January 1977 and a campaign to denigrate the dissent began, Father Malý decided that he agreed with the Chartists’ arguments and should sign the document, which he soon did: “I regarded the emergence of Charter 77 as a great liberation, because for me it was a kind of impetus to finding a way to clearly express my disagreement with the then system. Naturally I didn’t pull any punches even in sermons. However, I didn’t have directly political sermons – they reacted naturally to the atmosphere of the time but were always based on the Gospel. When Charter was founded it helped me express my civic responsibility.” Priests in Czechoslovakia were barred from serving publicly if they didn’t possess so-called state consent, an administrative permit that became an instrument used by the regime to persecute the church. It was very likely Václav Malý would lose his state consent if he signed Charter 77, so signatories and dissident friends tried to persuade him not to: “Nobody persuaded me to – it was genuinely my own decision. On the contrary, Ivan Medek (a musicologist, journalist and dissident) and Professor Ladislav Hejdánek (a philosopher and dissident) – with whom I later had a lot of contact – asked if I was aware that it would cost me my state consent, saying it would also have other consequences. I said: ‘Yes, I’m aware of that. And if I remain a priest, which I want to do, I am also a citizen and I decided to sign in that spirit.” At the end of 1978 Father Malý really was stripped of his state consent. In January 1979 he began working as an assistant land surveyor.

The same year he became involved with the Committee for the Defence of the Unjustly Persecuted, which provided assistance to political prisoners and their families and in particularly monitored politically motivated judicial arbitrariness, about which it informed the democratic world. Malý was arrested over his work with the Committee, investigated (on suspicion of “subversion”) and held in custody for seven months: “It was unpleasant because I was locked up there with murderers. For instance, I remember one fellow who was around 20 and had decapitated an accountant. She was the mother of two children and the murderer was later executed. I was also inside with a murderer who had killed his own mother with five blows of a scythe to the head. So it was really tough. In that little room where you had also had to carry out intimate bodily needs in front of the other person it really wasn’t pleasant. I was also afraid there. I got on with everybody but there was certainly mental pressure. But I also verified there that you don’t know what you will withstand and you can boost your endurance.” Václav Malý emphasises being in custody also reinforced his faith. “Prison helped me to realise once again what it means to believe without any external support. Because there I couldn’t serve mass or read the Scripture. I couldn’t rely on anybody else’s faith so I had to find the best within myself and somehow live through it. I regard those seven months, which I don’t in any stylise as heroism, a great gift with regard to spiritual maturity.”

Following his release from prison Father Malý was barred from ministering and worked in the boiler rooms of hotels in Prague. However, he did minister secretly, visiting Christians and serving mass. He was also involved in Catholic samizdat publication and provided help to dissidents from the country and small towns who didn’t have the support of opposition communities. In a regime in which virtually everybody feared the secret police it wasn’t hard to discredit decent people by circulating rumours that they were State Security informers. Malý also experienced this: “It hurt me most when it was put about, because of one priest, that I collaborated with the StB. Even Cardinal Tomášek and many in the church believed it and I was like a pariah. At a moment when I was being intensively interrogated and harassed some priests and Catholics believed I was an agent. That was the worst moment of my life and I basically couldn’t protect myself. The first ones to say it was nonsense were Ivan Medek and Zdeněk Bonaventura Bouše (a noteworthy priest, Franciscan and Charter signatory – author’s note).” From January 1981 until the following January Václav Malý was a Charter 77 spokesperson. He lived under constant police surveillance and was regularly spied on, interrogated and arrested. However, he refused to be scared and in fact his activities intensified – from 1988 he was also a member of the Czechoslovak Helsinki Committee.

During the 1989 Velvet Revolution Václav Malý became the spokesman of Civic Forum (an association of dissidents, students and representatives of other social groups), whose leaders held negotiations with top Communists. He chaired all sorts of meetings and alongside the abovementioned famous prayer on Letná Plain also made a play on words when he addressed the absent president, the chief normaliser and long-time general secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party Gustáv Husák, when he said: “Podívej se Gusto, jak je tady husto!“: (something like “Look how crowded it is here, Gustáv!”). Though the Czechoslovak revolution was “velvet”, the line caused some indignation within the Civic Forum and he decided not to speak in public again.

In 1990 Malý returned to public ministering at the Prague parish of St. Gabriel’s and later at St. Anthony’s. In 1996 he became canon of the metropolitan chapter of Prague and in the same year was summoned for ordination as bishop of Prague. He was ordained in January 1997 and chose as his bishop’s motto “modesty and truth”. As bishop Václav Malý continued to work for political prisoners and their families, this time in countries such as Belarus, Cuba and China. In 1998 he was bestowed with the Order of T.G. Masaryk, third class.

Text by Adam Drda