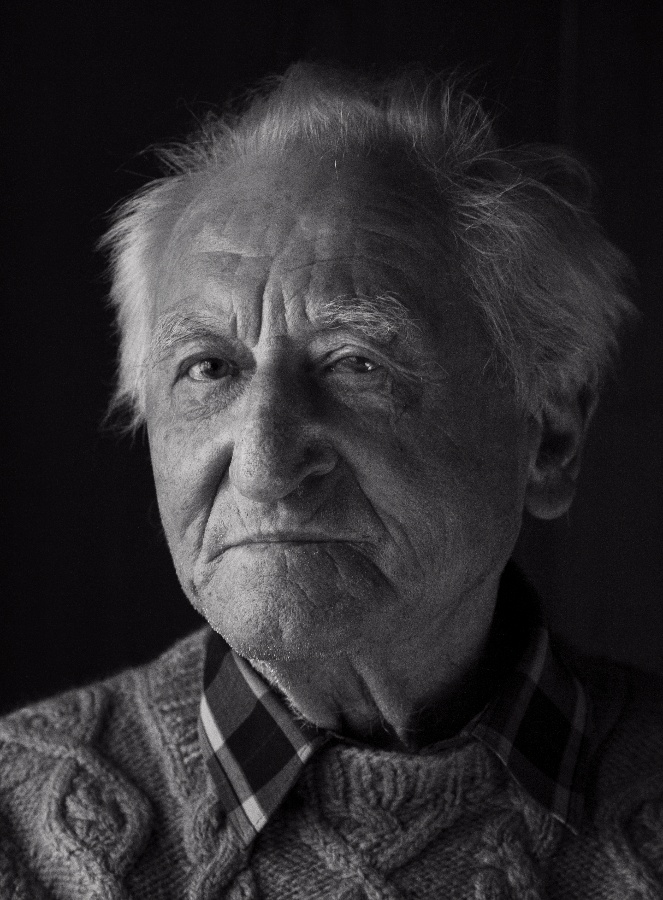

Miloslav RŮŽIČKA (*1925)

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

You can’t imagine the humiliation

The leaflets that Miloslav Růžička helped circulate called for free elections. This was after February 1948, when power had been seized by the Communists, who weren’t planning on allowing any free elections. They weren’t going to allow any protests, either. Therefore producing and circulating leaflets was highly dangerous. Just like any other form of protest.

In the autumn of 1949 Milada Horáková was arrested and sentenced to death in a show trial. The atmosphere in the country was full of fear. Růžička was careful. But that wasn’t enough.

“I duplicated leaflets on a typewriter and then distributed them to people I knew I could rely on. One time I ran into a neighbour. He said some declaration had appeared stating that distributing printed materials wasn’t allowed. He also said that if anybody received such a leaflet he was to report it. Then he asked if I by any chance I hadn’t written it. So I confided in him. I told him I had written it and that he wasn’t to discuss it with anybody. But by coincidence they arrested him and found the leaflet at his place. Then he was interrogated and they broke him… So they came for me. It was a done deal.”

They arrested Růžička on 12 December 1951. It was the toughest period of his life. “When they arrested me it was before Christmas. A friend from military service arrested me … a former medic, a good friend, but then he became a National Security Corps man. He put me in cuffs. I said we seemed to know each other. He didn’t respond. They took me to Pankrác. There I waited for the court verdict. Then I waited again and then they took me to Jáchymov. There I got sick. I got jaundice, so they took me to Karlovy Vary. There wasn’t a separate infections department there. So they bound both my feet with a chain. They put me among 10 normal patients. When I wanted to go to the toilet they had to unfasten me and I could go. With the chain the whole time, of course. What a racket! Such humiliation – you can’t imagine…”

Růžička spent five years in prison. In the interim his father was also arrested and his mother had to look after their private homestead by herself.

Following his return from prison Miloslav Růžička fought to preserve the memory of farmers and their families throughout the country who had been expelled from their farms and homes and had their land and property seized by the Communists.

Miloslav Růžička was born on 10 October 1925 in Vilémov in the Bohemian-Moravian Highlands. His father was a farmer and his parents had a private homestead. Miloslav Růžička began attending the municipal school in Golčův Jeníkov. However, when his father was mobilised he had to quit the school and return to work on the family farm.

He later studied at a business academy for two years.

Miloslav Růžička was involved in community life, being a member of Sokol and an amateur theatre actor.

The Communist coup of 1948 impacted his fate, bringing his previous way of life to an end. But the whole family were in danger.

He himself didn’t escape arrest after deciding to become involved in the resistance and copying and distributing leaflets. Using carbon copies, he produced around 100 of them. The leaflets called on people to write to the American Embassy and demand free elections. Růžička was caught by chance, after confiding in a neighbour. He was a member of a different resistance group. It was betrayed and the neighbour arrested. During a search of his home Růžička’s leaflet was uncovered.

Miloslav Růžička then spent five years in prison, for the most part in Jáchymov. “The worst situation was when I was in jail. Everything was hard there… Not just the hunger, the heavy work, thoughts of my parents… In Jáchymov I was also locked up in solitary confinement. One time a policeman came for me and took me off somewhere. He brought me to a villa. He said: Wash the dishes and the floors here now. I was so hungry from the solitary that I ate up a plate that the villa’s crew had left behind. The crew were the wardens who had brought us there. Then I swept and washed the floors. I was cleaning under the bed with a rag when a hand grenade rolled out. I immediately shoved the grenade back. If they’d seen me with that grenade? They’d have clobbered me. But I handled it.”

In the end he spent “only” three years in jail. His sister had applied for a pardon, which Miloslav Růžička actually received, from president Antonín Zápotocký, and got home. Unfortunately, however, his troubles weren’t over.

Following his return from prison he and his family were, as kulaks, in line to be expelled from their home. A unified agricultural cooperative, a collective farm, had been established. Luckily one reasonable man was found, a Communist who refused to sign the decision that would have led to Růžička’s expulsion. So he was allowed to stay and eventually saw communism come to an end.

He also saw the free elections that he had been demanding in the leaflets from the turn of the 1940s and 1950s.

However, after the fall of communism he learned that there was one group who had suffered particularly badly. They were farmers like him, but less fortunate. They had been expelled from their homes and lost their fields, property and even homes. Frequently without a trial. In many cases they were not only expelled but barred from their home villages.

Růžička began collecting such people’s stories and compiled and published them in a book.

“Why did I focus on the kulaks? I found out that they were a forgotten group. And they had probably been punished the most. I felt sorry for them. They suddenly found themselves far from home, somewhere by the Polish border, and were barred from returning.”

He contacted the former farmers by letter. However, some refused to discuss their sad stories with him. In the end he wrote a number of books, the best-known of which was “The Expelled: Operation Kulak – A Crime Against Humanity”.

In the foreword he wrote: “In our society the farmers, who were a kind of pillar of the nation, were perhaps the most conservative social group. In particular those families who had passed their farms down through generations, passing on tangible assets that included spiritual values. These people possessed an innate honesty and many always placed honour first; their word was worth more than written contracts today.”

Text by Luděk Navara