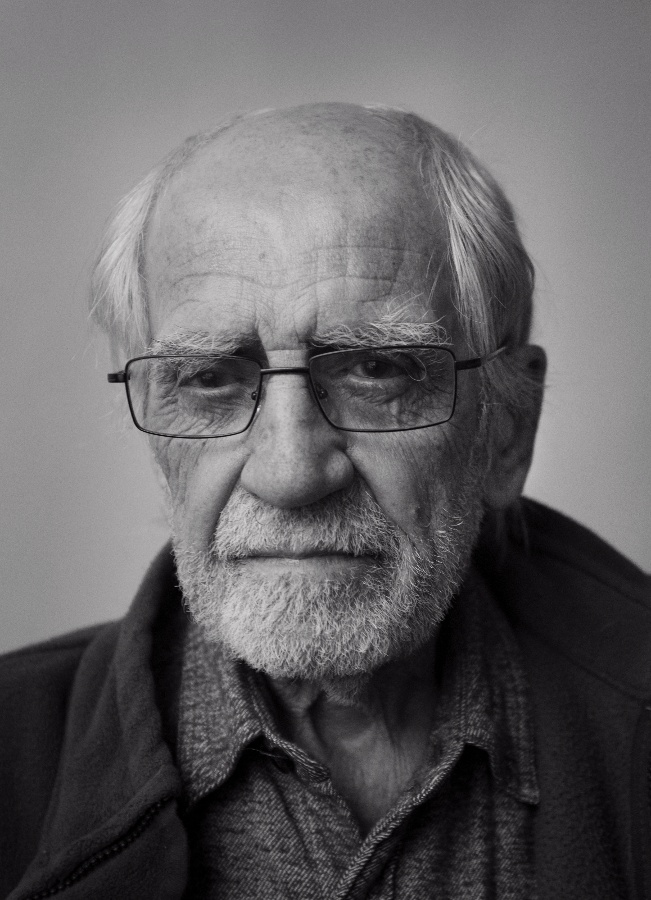

Jiří STRÁNSKÝ (*1931)

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

We won’t give them the pleasure

Jiří Stránský (*1931)

“One of our family slogans was: We won’t give them the pleasure. Meaning, we wouldn’t give anyone who was humiliating us the pleasure of letting them know we were humiliated. Others loftily said: I won’t bend, I won’t kneel, etc. We said it that way.” So recalls the novelist, screenwriter and journalist Jiří Stránský, the last surviving author of Czech “labour camp literature” who was imprisoned both in the 1950s and during normalisation.

Jiří Stránský was born on 12 August 1931 in Prague. His father was a lawyer and mayor of the Lesser Quarter Sokol community, to which according to tradition presidents Masaryk and Beneš also belonged. His maternal grandfather Jan Malypetr had been prime minister of two Czechoslovak governments in the interwar years and was the last chairman of the National Assembly prior to Munich. His father’s side of the family included A. B. Svojsík, founder and promoter of Czech scouting. As a boy Jiří Stránský attended Sokol and was also a member of the fifth “water” scouts troop.

Following the Nazi occupation of the Czech lands in March 1939 Karel Stránský joined the resistance and Jiří remembers a Gestapo search of their home when he was around 10: “They rushed into our villa. I had a kind of boy’s room where I was always screwing, drilling or cutting something. I was sitting there and suddenly dad came in and said to me: ‘Sit down here. If somebody comes don’t stand up – play! They turned the house upside down. Then they left and I found out that dad had hidden a revolver in my room.” Soon after the search Karel Stránský was arrested and sent to the Auschwitz concentration camp. He was released soon afterwards during an amnesty in connection with Hitler’s birthday. Following the assassination of Heydrich the Gestapo arrested him again as a neighbour, Vlajkař, had informed, saying he had celebrated the Reich protector’s death. As Jiří Stránský tells it, his mother followed her husband to the Gestapo’s Petschek Palace headquarters and asked to see an official, who released Karel Stránský, saying he had “saved his life during the first world war.” During the uprising of May 1945 Jiří, who was 14, was deployed as a runner carrying messages for the resistance leaders. For this he received a juvenile Distinction for Military Merit, second class after the liberation.

At the end of May 1954 the Czech National Council sent Karel Stránský to do some work in the borderlands. They had been predominantly occupied by Bohemian Germans for hundreds of years but Czech vengeance had begun with the wild and cruel expulsion of that population. “Father was brought up German. His mother was Austrian and as a boy he had spent the holidays with various relatives in the Ore Mountains in Egerland, which is the Cheb region. He knew the local dialogue Egerlander, which most Germans don’t understand. At that time the worst and most savage expulsions on the Western border were taking place around Hora Svatého Šebestiána. I persuaded father to take me with him.” Jiří says it was a tough but formative experience – he witnessed events that he would later draw on for his novel A Country Gone Wild.

In 1946 Jiří Stránský had a three-month study stay at an English school in Chateau d’Oex, Switzerland and in 1947 took part in the World Scout Jamboree near Paris. In Prague he attended a grammar school in Dejvice (on today’s Evropská St.), where he experienced the Communist takeover of February 1948. Many of his classmates were unsympathetic to the Communist ideology and the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia and were unafraid to show it. Jiří behaved similarly and came from a politically undesirable family, so he was barred from taking the maturita school leaving exam in 1950: “They gave me a choice: sign a request to be released from my studies for health reasons or be expelled for political reasons. In any case, my time as a student was up. I said I wouldn’t sign and they could do as they liked.” Soon afterwards he was expelled. Other members of his family, including his father, were also persecuted. Jiří found work as a carpenter at the Institute of Surveying for the Construction of Triangulation Towers (he had some experience, having briefly studied carpentry). After several months, however, he was injured at work. Through family acquaintances and thanks to his language skills he got into the posters and advertising division of the Čedok-Propag enterprise, where his job was to produce foreign language versions of promotional leaflets.

In 1952 Jiří Stránský was conscripted into the army, to an Auxiliary Technical Battalion (a punishment labour unit for “politically unreliable” soldiers). In the meantime, however, the State Security had arrested his boss, originally the owner of a classifieds company, who in fear for his life concocted accusations against various people to show the StB he was willing to collaborate: “He made up stories about 13 of his colleagues and the worst one was about me. He claimed the organisation had sent me for a six-week course to West Germany, where I was to have been trained in handling a transmitter but also, for instance, in silent killing techniques. (…) On the basis of such nonsense the police came for me in January 1953 at my Auxiliary Technical Battalion unit, whereupon they almost beat me to death because they wanted me to confess. But I didn’t know to what. In the end I hoodwinked them, not confessing to the charges to the StB men but admitting I had known about some anti-state activities and hadn’t reported them.” In a fabricated trial Jiří Stránský was sentenced to eight years in prison for treason and espionage.

Following his conviction he first worked as a bricklayer at Pankrác prison and as a tiler at Ilava in Slovakia. In October 1953 he was sent to the Vykmanov assembly camp in the Jáchymov area and then to mine uranium at the Svatopluk camp in Horní Slavkov, where he wrote the first notes for later short stories. In May 1955 he was transferred to the Vojna prison camp near Příbram as a breaker/digger operator. He took part in protest strikes and hunger strikes against the wholly inadequate conditions and was later moved to the Bytíz camp. In prison, Stránský got to know the jailed writers František Křelina, Josef Knap, Jan Zahradníček, Zdeněk Rotrekl and Karel Pecka. They had a major influence on his decision to devote himself to literature. He speaks of the labour camps, where a considerable part of the Czech intellectual elite ended up, as among other things a prison university: “When I had the morning shift from 6 to 2 pm, they woke you at 3 in the morning and you returned in bits at 3 in the afternoon. After work people could talk in their rooms. Four of them sat and spoke. I observed. I rarely said anything. I was glad they let me stay. They were a lot smarter and better educated than me. (…). There was an excellent art historian, Bonny Falerský, and he ran an art history seminar. We made a deal with a civilian, who bought all the postcards reproductions of works at the National Gallery and Falerský used them to teach us aesthetics. (…). Everything had to be hidden as the wardens found and destroyed them during searches.”

In around the middle of the 1950s, Jiří’s father Karel Stránský filed a complaint for violation of the law in a bid to have his son released. “In 1958 an investigating judge came to see me, a former military prosecutor who had hung I don’t know how many people. He came to report that I was inside wrongfully, that I could immediately go home, and that I was just to sign some formality. He handed me a piece of paper where it said I was applying for a pardon. So I said: But you told me I was innocent, so why should I apply for a pardon? So I stayed in prison two more years. On top of that I got solitary for insolence.” Jiří Stránský got out of prison during the “big” amnesty of 1960.

Following his release he worked digging and laying concrete at a water purifying plant at Prague’s Troja and later briefly on the construction of the Podolí swimming stadium. In 1962 the magazine Mladý svět published Stránský’s short story Vašek (The Idiots); it caught the eye of director Martin Frič and Stránský later worked with him as assistant director. He began working in film and television, though as he was unable for political reasons to find a permanent position he took work at a petrol station on Opletalová St. in 1965. After the Soviet occupation he decided to go into exile. He spent time in Austria and France but in the end returned home. In 1969 his first short story collection Happiness, based on his prison experiences, was published. However, after an official ban almost the entire print run was destroyed.

During normalisation Jiří Stránský worked once again at a Benzina enterprise filling station. In December 1973, shortly after he had given his employers notice, he was arrested by the police for a second time. He was convicted on the back of a false accusation of alleged black market petrol dealing, officially dubbed the theft of property in socialist ownership. “I was by then working for the Semafor theatre. But the theatre didn’t give me a full-time job. I subsequently learned the StB had told them not to take me: ‘We’re planning to lock him up but we don’t know how yet.’ Then the criminal police arrested me but there were two StB men in the office and they said: ‘Now we’ve got you – as a burglar.’ They really got me that time. (…) They charged me with stealing petrol, which wasn’t true at all. But they threatened all the others that they’d throw the book at them if they didn’t testify against me. So I was inside for two years for stealing national property. But I’m able to do that – to go inside for something that’s not at all true.” Jiří Stránský was in prison in Bělušice near Most and at Bory in Pilsen. From 1975 he worked as a stagehand, stage master, transport chief and occasional director at the State Song and Dance Company.

It was only after the fall of the Communist regime that Stránský could earn a living as a writer. He refused to enter politics and was president of Czech PEN from 1992 to 2006. He published a number of books, including the novels A Country Gone Wild and Auction (1997), on the basis of which he also wrote the screenplays for a TV series. His prison writings and screenplays provided the basis for the films Boomerang (1998) and A Piece of Heaven (2005). Jiří Stránský is a recipient of the Egon Hostovský Prize (1992) and the Karel Čapek Prize (2006). He continues to produce occasional journalism and lectures at Czech schools about his experiences.

Text by Adam Drda