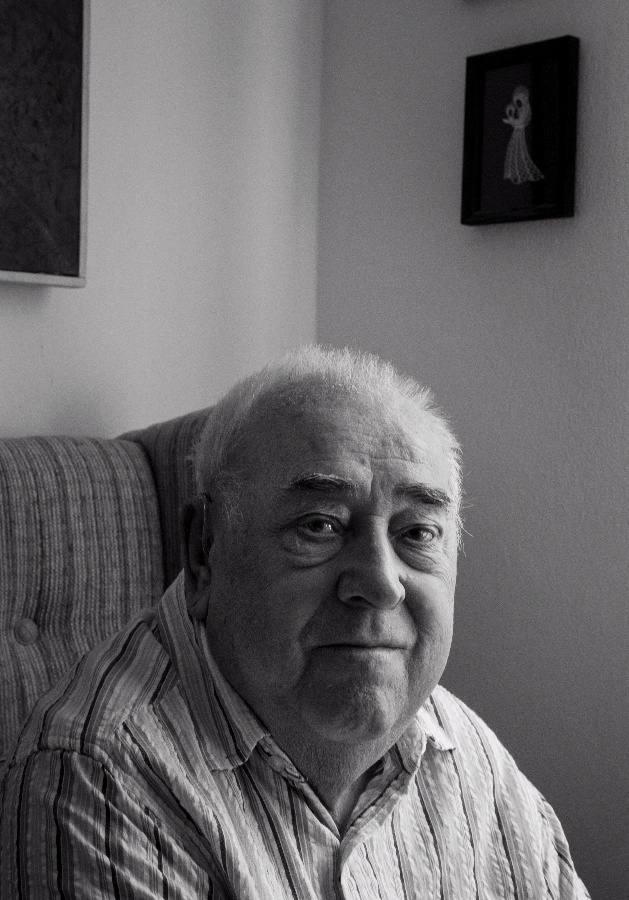

Ladislav SUCHOMEL (*1930)

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

I never regretted anything

Ladislav Suchomel (*1930)

They surrounded their resistance group at a moment when they were all hiding in the attic of a remote building in the valley of the small Libochovka river in the district of Tišnov. The leader of the group, Milan Havlín, was the first to spot the gunmen. “I was already awake. We were in the attic, on hay… and he – by which I mean Milan Havlín – sprang up and pointed them out to us. I can’t recall the details exactly… Havlín went outside and they started shooting as they came out of the forest,” says Ladislav Suchomel, describing a key moment in his life. He was arrested, just like the others. In total six young people. “Three girls, myself, Milan Havlín and Pepík Oliva.” They had silently surrounded them in them in the night and in the morning had everything under control. The situation seemed hopeless. “They were shooting but we didn’t defend ourselves… so they were shooting… but we weren’t,” he says. “Naturally I was scared. They then laid us down outside on the bank of the Libochovka. They told us we couldn’t move and to just lie on our bellies, heads down. But I looked to the side. Then I got such a stamp on the neck that it hurt for a fortnight. That’s when I was most scared. I didn’t know what would become of us. They then took us off to a Black Maria.” This is how Ladislav Suchomel describes his dramatic arrest at the village of Rojetín in the Tišnov district on 2 October 1949. Imprisonment followed. Suchomel was sentenced to 19 years and spent a long 14 in jail. He wasn’t released until 1963.

Ladislav Suchomel was born on 21 July 1930 in Tišnov. His father worked as an orderly at a psychiatric clinic in Brno’s Černovice district. Suchomel trained to be a bookseller and got a job at a printing company in Brno. He recalls from the pre-war era the poet Jan Zahradníček, who wrote for the magazine Akord, as Suchomel was once tasked with taking something to his office. “I knew I was making a delivery to the poet Zahradníček. Of course I knew who he was. But I didn’t know how to address him. Zahradníček asked: ‘What have you got for me?’ I said: ‘Master, our boss has sent this to you.’ I called him ‘master’ because nothing else came to mind,” says Suchomel. Then his boss heard about it. “He said to me: ‘You nitwit, he’s no master carpenter.’ So that’s how I met the poet Zahradníček,” Suchomel says.

However, Catholic poetry, along with all free writing and free living, came to an end in February 1948. The printers where Suchomel worked – first as an apprentice and then as an employee – mainly produced Catholic literature. Soon after the Communist coup he became involved in resistance activities. He began delivering leaflets.

“I did the leaflets with Břetislav Jeník, whose father had a bookshop in the arcade of the Moravian Bank in the centre of Brno. He printed them and then I distributed them. At that time I’d completed my apprenticeship,” Suchomel says.

Many other courageous young men also attempted to fight the nascent totalitarian system. One of them was Milan Havlín, a student two years older than Suchomel. Also from the Tišnov area, Havlín was one of the founders of the resistance group Lilka. He was arrested in southern Moravia and, having feigned epilepsy, ended up at the psychiatric clinic in Brno’s Černovice where Suchomel senior was an orderly. When Havlín managed to escape from the clinic he began cooperating with his son, Ladislav Suchomel, in the resistance in the Vysočina region.

Meanwhile, Ladislav Suchomel was at that time forced to go underground as he had almost been apprehended while delivering leaflets. “They nearly caught me doing it, so I fled to relatives at Rojetín in Vysočina. Then myself and the others hid out in Vysočina,” Suchomel says. He had been working with Milan Havlín and his friends, who were also organising resistance in Vysočina. “The group were active around Rojetín. Milan Havlín was the leader and I was his deputy. Not that that was decided or voted on.”

Named Jánošíci (after Jánošík, a Robin-hood like figure), the group attempted to intimidate Communist officials. They wanted to take their party cards but not threaten their lives. On 27 September 1949 the group went to the home of the chairman of the Communist Party in Rojetín, Emil Kvasnice, taking party materials and a gun. However, this brought them to the attention of the secret police, who hatched plans for an extensive round of arrests.

“We were planning to leave for the West. But Milan Havlín looked after that. He had the contacts, so I wasn’t involved in that,” Suchomel says. However, by then Havlín had long been in the sights of the secret police, who were monitoring his activities. This made it easy in the end to make the arrests at Rojetín at the start of October 1949. None of the group put up any resistance. “I was arrested on 2 October 1949 and waited for my court date, which took place on 31 January 1950. The trial was of the group Havlín et al. I got 19 and a half years in prison and spent two months short of 14 years in prison.”

In prison Suchomel met Josef Robotka, an important member of the anti-Nazi resistance and co-founder of the group Rada tří (Council Three). He had been arrested by the Communists after the 1948 takeover. “When they brought us to Znojmo I was with Colonel Josef Robotka, who they later executed. He didn’t know he was to be executed, but he sensed it so he kind of expected it. After all, he’d previously been in Moscow. They put me in with him. He suffered from sciatica and I was evidently to look after him. He told me: ‘They’ll invite you to Příční St. in Brno, boy. There’s an interrogation centre there and they’ll pay you a little and send you home. Me they’ll hang’… And you know, he was right. I didn’t learn about his death until later. In Plzeň, at Bory. A fellow inmate told me.” Suchomel recalls with horror being left in solitary on New Year’s Day. “When they took Robotka off to Znojmo I was in solitary. It was terribly cold. I was as frozen as an icicle. They them took me from there to Brno to the court,” he says. Robotka was executed in Prague on 12 November 1952.

“I experienced the greatest fear in the Cejl prison before going to court. They told me my lawyer was there and he questioned me as if he were an StB man. I asked how things looked. He said the death sentence was proposed for the first six. I was second in the text of the arraignment. I was scared they’d hang me… I was in cell number 29 at Cejl. I’ll remember that number my whole life.”

In the end none of his group was executed. In Milan Havlín’s case it was a close thing, however; they commuted his death sentence only because of his youth.

In 2011 received the order of T.G. Masaryk for his outstanding service in the development of democracy, humanity and human rights. “I never doubted what I was doing. It was the right thing. I never doubted even in the worst times – neither in the Bory prison in Plzeň or anywhere else,” he says.

Text by Luděk Navara