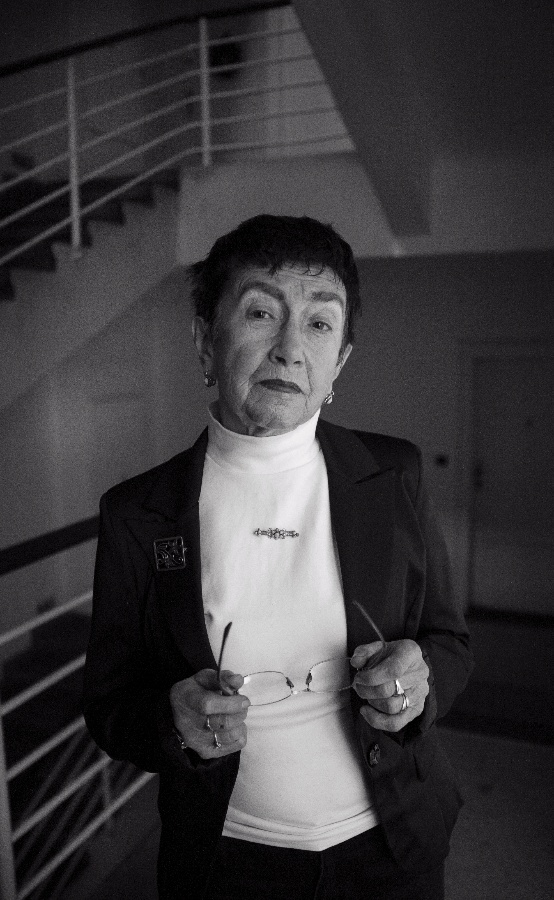

Jiřina ŠIKLOVÁ (*1935)

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Imprisoned for smuggling books

Jiřina Šiklová (*1935)

In May 1981 the sociologist and journalist Jiřina Šiklová was sentenced to a year in prison for subversion. “If I’d known that I’d only be there for that year – it’s a trifle. Then, it is interesting for a sociologist,” she says. The problem was that the charge in question could have brought a term of up to 10 years. Nobody knew under the Communist regime what kind of major trial they could find themselves involved in, whether an example would be made of them. In the end Jiřina Šiklová withstood prison admirably. She wrote love letters for her fellow prisoners and various official letters, including divorce petitions, for wardens.

Jiřina Šiklová was born on 17 June 1935 into the old Prague Herold family. Her father, a doctor and Social Democrat, influenced her through his politics and humanism. One of the strongest memories of her youth is of her father treating several people from Plzeň injured during protests against currency reform in 1953 (the reform stripped thousands of people of their money and savings; in Plzeň many demonstrators were arrested, imprisoned, thrown out of their jobs, etc.).

After graduating from grammar school Jiřina Šiklová enrolled at Charles University’s Faculty of Arts, where from 1953 to 1958 she studied history and philosophy. She then became an academic assistant and developed a deeper interest in sociology, a subject rejected by Stalinists. Thanks to a partial relaxation, a separate sociology department was set up at Charles University where Jiřina Šiklová did research into student movements and other subjects. She became a member of the Communist Party in 1956. She says that she had rejected previous offers of membership but after Khrushchev’s speech (criticising Stalin) she thought things might improve in the country. However, that took several years. From 1967 she was active at the faculty in the reform wing of the Communist Party and in the so-called renewal process that culminated in the Prague Spring of 1968 and ended with that year’s Soviet occupation.

At the start of normalisation, in 1969, Jiřina Šiklová (alongside, e.g., Jan Patočka, Milan Machovec and Karel Kosík) was among the “first wave” of academics thrown out of their jobs for political reason. She stood down from the party. Until 1989 she was barred from any intellectual profession and worked as a cleaner, in administration and finally as a social worker at the geriatric section of Prague’s Thomayer Hospital. She made rich use of that experience later when she established the subject of social work, while she has explored aging and death in her lectures and books.

From the early 1970s Šiklová was involved in opposition activities. The lawyer, dissident and later politician Petr Pithart, who had returned from studies in the UK, gradually handed over to her responsibility for the smuggling of banned literature, which she co-organised with Jan Kavan’s London-based independent press agency Palach Press Agency. Jiřina Šiklová looked after handover and distribution, conveying packages for exile publishing houses to couriers. In this way representatives of a broad spectrum of the Czechoslovak opposition – including Petr Uhl, Rudolf Slánský, Rudolf Battěk, Ivan Havel, Otka Bednářová, Milan Šimečka from Bratislava, Evangelical cleric Jaroslav Šimsa, members of the Committee for the Defence of the Unjustly Persecuted and many others – got their texts across the border. “It involved encoded letters, messages, sometimes essays, manuscripts on carbon paper. They weren’t books, but things you could stick inconspicuously in your pocket. I had a coat made for that purpose with special pockets, in case somebody searched me. When the police search you they go over you from top to bottom, then the legs and unobtrusively at the crotch. But there are places – for instance at the knee, or the bottom – where they didn’t search. And that’s where I had a pocket cleverly sewn so they wouldn’t find it,” she recalled in an interview for the weekly Respekt in 2015.

By contrast, the couriers mainly delivered into Czechoslovakia books from exile publishing houses, as well as magazines such as Listy, which Jiří Pelikán published in Rome, or Svědectví, which Pavel Tigrid ran in Paris: “I always just organised a garage with somebody where the consignment was to be brought. Then I met the courier (…) and told them the address where they were to arrive by car at a given time. The car with the courier then went inside or parked near the garage and then loaded or by contrast unloaded the consignment. The garages alternated. Sometimes it was a garden or cottage, a small house. Quite often it was an Evangelical rectory, where foreign cars could also arrive without being really conspicuous. Every place was used at most around three times, so the neighbours wouldn’t notice. Admittedly Kavan didn’t change the car. But every time they gave it a different number and almost every time a different driver. They knew what they were carrying.”

Jiřina Šiklová’s (incidentally she was also a Charter 77 signatory) organising work escaped the attentions of the State Security for a long time. However, in April 1981 after a denunciation a caravan driven by Eric Thonon and Franćoise Anis from France was apprehended at the Dolním Dvořišti border crossing. The pair were arrested and their load seized. At the start of May the StB then arrested dozens of people and attempted to organise a large show trial dubbed “Šiklová et al”. Jiřina Šiklová and Jan Ruml, who had directly participated in the smuggling, were remanded in custody, as were historians Ján Mlynárik and Martin Šimečka, writer Eva Kantůrková, poet Jaromír Hořec and journalists Jiří Ruml and Karel Kyncl. As mentioned above, they were charged under article 98 with subversion and faced sentences of up to 10 years. However, thanks to sizable international protests the Communists released them without a trial in March 1982 (French president Francois Mitterrand and Austrian chancellor Bruno Kreisky interceded at the time on behalf of the detained).

Following her release Jiřina Šiklová continued to organise the smuggling of packages, this time with the help of diplomats at the Swedish, German and Canadian embassies, the US NGO Helsinki Watch, which monitored human rights in Eastern European states, Karel Schwarzenberg and other individuals and institutions. Replacing Jan Kavan, Vilém Prečan took care of operations abroad. He had built up the Documentation Centre of Czechoslovak Independent Culture, which gathered exile and samizdat literature, at Schwarzenberg Castle in Scheinfeld, West Germany.

Following the collapse of the Communist regime in November 1989 Jiřina Šiklová could return to her academic work. Her experience of working in hospitals and opposition activities (including her spell in prison) had deepened her interest in social and human rights issues. One of those who had supported the Czechoslovak opposition financially and organisationally was the Holocaust survivor, exile and official of the Office of the United Nations High Commission for Refugees Tom Luke (Löwenbach), who Jiřina Šiklová had met when he visited Prague in 1987: “After the revolution Tom organised for me to take part in a conference on migration policy in Vienna, saying that sooner or later asylum seekers would begin coming to free Czechoslovakia. I doubted that but still went to the conference. Thanks to this, from September 1990 I was able to include the question of the integration of foreigners and subject of asylum policy in lectures at the Prague and later Brno Faculty of Arts. We were at least a little surprised when before long refugees from the war in the Balkans began arriving in our country.”

Jiřina Šiklová played a key role in the establishment of the Department of Social Work at Charles University’s Faculty of Arts and began heading it at the end of the 1990s. From 1991, in cooperation with Jana Hradilková and others, she began to establish Gender Studies in the Czech setting, built up a library of feminist literature and helped spark a debate on feminism. Her role in the introduction of gender issues to teaching at Czech universities has been enormous. She has published a great number of articles in Czech and international journals and is the author of books introducing readers to social issues from intergenerational relationships to perceptions of aging and death. She has received many honours (e.g., European Woman of the Year in 1995, the order of T.G. Masaryk, first class, for services to the country) and very often engages in public debate on political and social issues through lectures, discussions and articles.

Text by Adam Drda