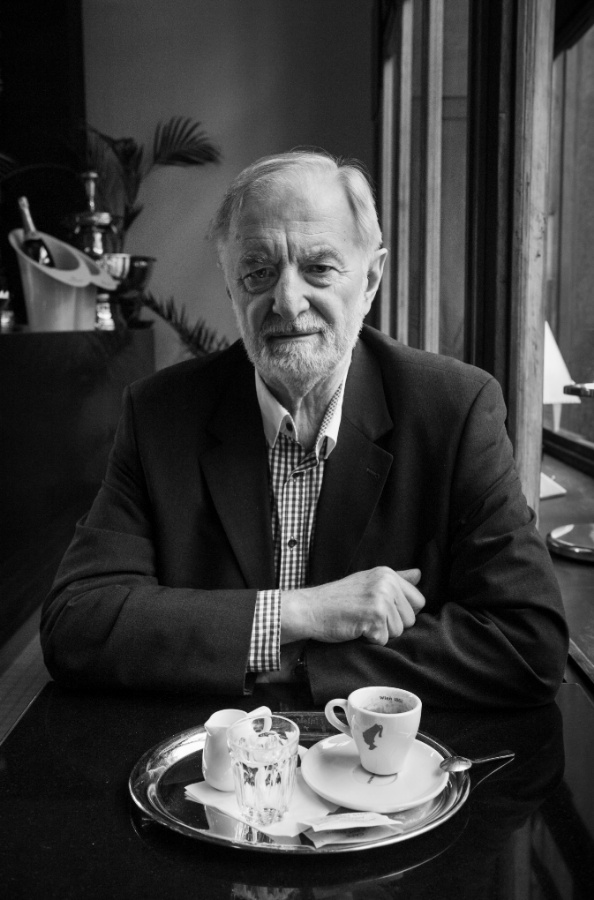

Eugen BRIKCIUS (*1942)

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

I was, to put it mildly, pleasantly surprised when communism fell

Eugen Brikcius was born in Prague on 30 August 1942 into the family of a philatelist. From childhood he was interested in art. His parents encouraged his talent and funded private lessons with an academic painter. Following his graduation from secondary school in 1959, Brikcius was unable to get into any university in view of his anti-Communist views and was forced to make a living as a labourer. He first worked on military construction projects and later operated a forklift at a train station before becoming an assistant at a paper works and ending up at a research computing centre. In his free time Brikcius studied philosophy and theology, focusing on the works of St. Thomas Aquinas. He was interested in art and attended Hejdánek’s ecumenical seminar on Prague’s v Jirchářích St. It wasn’t until 1966–1968 that he was able to study, by correspondence, philosophy and sociology at Charles University’s Faculty of Arts.

In the mid-1960s he began organising public happenings, leading to a clash with the totalitarian regime. His first major “artistic” happening, a staging of Zeno’s paradox of Achilles and the turtle, was intended to impress a girl. During another event in 1967 he and some friends arranged half-litres of beer on a street on Kampa, which the regime regarded as provocation. “The police came but didn’t lock anybody up that time. They took our names and broke the event up.”

That same year he put on a happening entitled The Bread Mystery in the gardens of Prague Castle. “The girl I was after sat on a Baroque arch and we climbed the steps and laid a mythical pyramid of loaves at her feet.” The police made dozens of arrests and confiscated the bread. With this attempt Brikcius again failed to win over the girl, though he did appear in court and received a three-month jail term. He appealed on the grounds that it had been art and escaped prison.

At that time Jindřich Chalupecký found him a place at the Václav Špála Gallery, where he was finally able to work in the field of art. In autumn 1968 he went to the UK to study at London’s University College. He was accompanied by his future first wife, whom he married in London. They could have remained abroad but felt Bohemia was their home and returned voluntarily to their occupied homeland in 1970.

When normalisation took hold Brikcius found himself among dissidents. He was arrested in 1973 with friends Jaroslav Kořán, Ivan Daníček and Ivan Jirous for disorderly conduct and defamation of nation, race and conviction in a pub. “Things kind of took off… We got into a conflict with a retired StB major. Jarda Kořán knelt before him and said: ‘Bald Bolshevik give us a pike, we’ll stick you in the belly’. Magor [Jirous] ate Rudé právo.” What’s more they sang “drive the Russians out of Prague”. The StB man called the police and they ended up in court. Brikcius was sentenced to 14 months, reduced to eight on appeal. He served the term at Oráčov prison, where he tamped tracks. Thanks to his aptitude for languages he learned Latin while in custody and jail.

Following his release he was employed in labouring professions and was a water measurer for three years. At the same time he translated from English and began writing poetry in Latin. At Christmas 1976 he became one of the first to sign Charter 77, before it had been published. “I signed it because I realised that if I had written the text myself I would have written something similar. I lived according to the Charter my whole life, even without it existing.” Signing the Charter earned Brikcius greater attention from the forces of repression and for the next three years he was under constant StB surveillance. He was frequently interrogated and arrested for short periods and the harassment intensified.

Brikcius regarded the collapse of the Communist regime as a completely unrealistic possibility. “I wanted to live normally. I got tired of that fact I could go to prison for three years over anything and be persecuted every which way.” He decided to emigrate to Austria. His father bought him a plane ticket and he flew to Vienna in January 1980. “Ivan Medek was waiting for me. We had a glass of wine and he gave me the key to a hotel room.” He later acquired a small apartment on the outskirts of Vienna. He started from scratch. His wife and children had remained in Czechoslovakia and he got divorced.

His aim was to leave Austria for the UK and, after a decade, complete his philosophy studies. However, he failed to receive a visa. After the intercession of the university in London he eventually received at least a scholarship visa, conditional on his returning to Austria on the completion of his studies. So in 1981 he left for a year and completed his philosophy degree. He then settled in Vienna, where he worked as an official at a branch of the US refugee agency HIAS tasked with interviewing Jewish migrants. “We received Jewish refugees from Iran who wanted to travel to the US, where they had relatives.”

He remarried in Austria and had a son. He remained in contact with friends in Czechoslovakia from Vienna but didn’t foresee the fall of communism. “I thought it was a thousand-year empire. I was, to put it mildly, pleasantly surprised.” He first returned to Prague in April 1990.

Eugen Brikcius has written several poetry collections, prose works, screenplays and other texts, including the autobiography Můj nejlepší z možných životů (My Best of All Possible Lives) and the novel Nepředmětná Odyssea (The Intangible Odyssey). He received the Jaroslav Seifert Prize in 2015 for the collection A tělo se stalo slovem (And the Body Became the Word) from 2013. In 2017, the Austrian ambassador presented him with the Honorary Cross for Science and Art, first class. He has never written on a computer but continues to use a typewriter. “Somebody has always had to rewrite my texts. If I used a computer it would destroy my thoughts.” He lives alternately in Vienna and Prague.

Text by Jan Horník