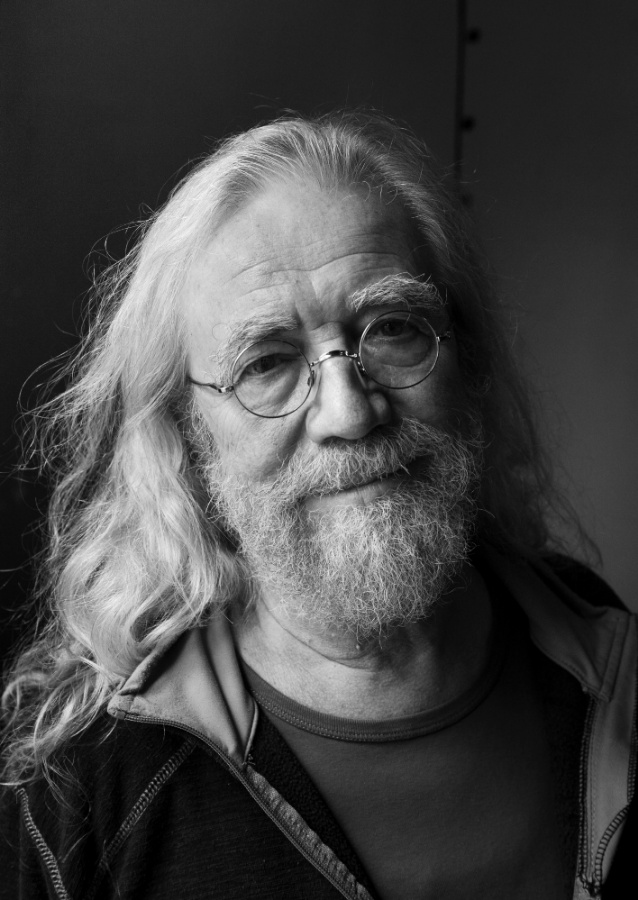

Jaroslav HUTKA (*1947)

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

It was tough when my father died and I couldn’t go to the funeral

Singer-songwriter Jaroslav Hutka derives most pleasure from the fact he needn’t be ashamed of what he did in the period Czechoslovakia had a Communist regime. “I’m quite pleased about the fact they weren’t the ones on top for the most part. They didn’t take away my freedom, and in the end I was able to help many people to bear that imbecilic regime better, which is great.”

As a troublesome songwriter, Jaroslav Hutka was hounded into exile in the Netherlands by the regime and in the initial years it appeared he would never return. The Communists wanted rid of their critic for good. “In the first few years I guess I more than anything regretted exile. It seemed to me that I’d destroyed everything that I’d done up to that point and ultimately also destroyed myself. Fortunately, everything turned out differently in the end, and today I’m glad of having been in exile. Otherwise under the Bolsheviks I wouldn’t have had the chance to learn foreign languages and to get to know the West not as a tourist but as somebody who lives there and is familiar with everyday life,” he says. However, he did experience moments of genuine hardship following his emigration. For instance, when his father died in Czechoslovakia, behind the Iron Curtain. “I was in exile and couldn’t go to the funeral. It made me feel so bad that I thought I’d become sick and went to a doctor in Holland for the first and last time. It’s a long story, but I left him healthy and in a pretty good mood.”

Hutka entered public consciousness as a musician who succeeded in singing freely in a time of oppression. He signed Charter 77 and came into conflict with the regime repeatedly, for instance as the writer of songs that referred to Václav Havel, a leading dissident and banned playwright. Hutka returned to his homeland right after the fall of the Iron Curtain, in November 1989, and on the same day sang at a demonstration at a packed Letná Plain in Prague. It is an image that has remained with many.

Jaroslav Hutka was born in Olomouc in 1947. His parents owned a building there in which his father ran a furniture shop. In 1948 both the shop and the building were nationalised. Four years later, before Christmas, the family was forced to move. Volunteer border guards with machine guns came to take them away to the countryside. Hutka was four years old. The family received one and a half rooms in a small village 50 kilometres from Olomouc. A decade later Hutka moved to Prague, where he wrote poems and studied at an arts-focused vocational school. He began writing songs in 1966 and met the songwriter Vladimír Veit at a club on Národní St. The pair formed a duo and found success, though that idyll was shattered by the Soviet invasion of August 1968. Hutka still recalls that insane night. They were riding a taxi into the city centre and were stopped by an enemy armoured vehicle. They got out. As strange as it sounds now, he didn’t want to pay the taxi driver. Hutka and his girlfriend saw a city in shock, watching as crowds of bewildered people first moved toward the Central Committee building before later streaming towards Czechoslovak Radio. Desperate fighting took place at both places.

After August 1968 came August 1969 and it was clear the occupiers had found so many highly willing lackeys that they themselves needn’t leave their barracks. The country again became a dictatorship. The Iron Curtain descended and there was a threat of arrest and prison. People felt that invisible pressure and wished to resist it. Hutka’s songs began to help them. “I didn’t feel like it was some kind of political defence. It was intended to be about life and it just flowed from that, as if of its own accord. It just came out,” he says.

The StB took an interest in Hutka from the mid-1970s, when a snitch sent the StB a recording of a concert he did in Choceň. Secret police officers began to follow the popular songwriter under an operation rather unimaginatively entitled Singer. However, Hutka evaded them. As they themselves admitted, he was too clever for them.

“Steps have not been taken to accelerate the launch of the criminal prosecution because HUTKA’s crime is carried out by means of sophisticated actions that impose marked demands as regards proof. In his performances HUTKA doesn’t attack openly but ambiguously. However, he gives listeners instructions on how to interpret his performance when he says: ‘So it has come about that I make that which is best, freest and least problematic clear by means of unarticulated sounds, under which I can imagine whatever I wish and nobody will understand.’” Further: “That ambiguity makes it possible for HUTKA during questioning to have considerable room for ‘manoeuvre’ and for explaining the meaning of individual words, which will be advantageous to him.”

A report by the secret police dated 28 February 1977 refers to alleged criminal activity: “Since 2004 Jaroslav HUTKA has been performing as a folk song singer and guitarist in the ŠAFRÁN free association of singer-songwriters…”

Hutka also entered public consciousness for a song he wrote about Václav Havel featuring the line: And according to the letter of the sword-like article, they’re now ruminating on the rights of Havlíček – Havel [this rhymes in Czech]. Naturally, this song attracted the interest of the StB, as it demonstrated that parables remained effective. Under the Hapsburg monarchy the secret police were interested in Havlíček Borovský, just as the Communist dictatorship was in Havel. In both cases because of what they wrote and what they criticised. The song was written in February 1977, when Havel had been jailed for the first time.

Because of the song the StB arrested Hutka too, and he spent his first night in a cell on Prague’s notorious Bartolomějská St., home of StB HQ. It was May 1977. “It was a rather absurd experience. The whole interrogation was about who the song Havlíček – Havel was about. They insisted it was Havel. I said Havlíček Borovský. I wouldn’t back down, so they released me.”

On 21 December 1977 the Communist minister Jaromír Obzina signed a secret order under which inconvenient citizens were to be evicted from the country. If they resisted, by means of violence, harassment, blackmail and psychological terror. The operation was named Clearance and was targeted against Charter 77 signatories and others. The choice was clear: eviction or jail. When Jaroslav Hutka received his first offer of emigration from the StB in mid-1977 he didn’t take it seriously. But eventually they forced him out under threat of trial for unauthorised business dealings and after barring him from performing. Even before this he and his wife had been made to give up their Czechoslovak citizenship. This was a secret police condition… The troublesome singer and his wife had no nationality, no property and no chance of return. They drove their old Škoda to Rozvadov. Instead of emigration passports, they had documents reminiscent of certificates. They entered the border zone and a soldier doing checks waved a machine gun under their noses. They found a new home in the Netherlands. Hutka sang and played for exiles. There were many, albeit scattered around the globe. In the end it didn’t last so long. When the Czechoslovak regime fell, starting on 17 November 1989, Hutka was one of the first exiles to return. The border system had not yet adapted to the new situation, so a visa cost him 70 marks. He paid it and went home. An audience of 100,000 awaited him at Letná. It was the most wonderful performance of his life.

Text by Luděk Navara