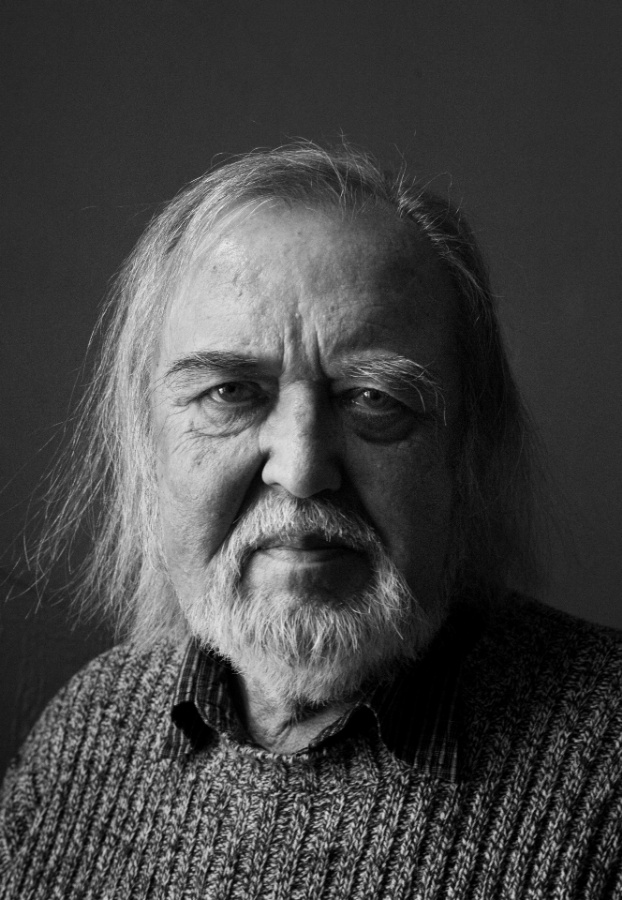

Vladimír KOUŘIL (*1944)

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

I thought they’d let us be. Perestroika had begun. But I was wrong

Vladimír Kouřil was born in Těšetice near Olomouc on 10 November 1944. His father was a gendarme on the border around Javorník where, prior to the seizure of the Sudetenland, he had taken part in battles with the Germans at Frýberk, Bílá Voda and Zighartice. The family of his mother, nee Mencová, came from the Krkonoše Mountains and she greatly shaped his relationship to literature, the visual arts and music. His parents had met in Těšetice but the family moved to Prague’s Letná district in 1949. His father had joined the Communist Party four years earlier and remained a member until 1968. Following the dissolution of the gendarmerie he was transferred to the border guard in an economic position in Prague. In the 1950s he lost that job due to having been a First Republic gendarme. He wasn’t rehabilitated until the 1990s.

When it comes to politics during his elementary school days, Vladimír Kouřil recalls going to watch Klement Gottwald’s funeral procession in 1953. “The crowds didn’t weep,” he says. He later enrolled at a vocational school focused on water management construction. He began listening to music, mainly rock’n’roll and jazz, in his first year. “The rock’n’roll era had just begun. Miki Volek, Pavel Sedláček and Petr Kaplan appeared at Socialist Youth events. I was utterly bowled over by the music,” he says. He didn’t have a record player or even records at home and chiefly listened to the radio. Music became the hobby of a lifetime.

Politics played virtually no role at the vocational school in the early 1960s and the whole class automatically became members of the Czechoslovak Union of Youth. “We were supposed to go to May Day parades, but we skipped them.” Kouřil regularly followed politics. Most of his classmates were opposed to the regime, repelled by censorship of the arts and the impossibility of acquiring literature and music. Following his school leaving exams he applied to the Czech Technical University. He left the faculty three years later and got a job as a construction firm driver’s assistant before joining the Water Management Research Institute.

In the late 1960s the atmosphere of the totalitarian regime gradually became more open. Kouřil followed talks with the Communist regime’s leaders that began to take place. “All of a sudden they spoke in a totally ordinary manner, which was a huge contrast with the 1950s.” He was convinced the transformation of society was on the right track and would prove successful. He did not believe there was a danger Brezhnev would take action against the Prague Spring. When the August 1968 invasion began he was doing military service on Prague’s anti-aircraft defences. He had been deployed there on 1 August. “I was lying in bed in the sick bay when somebody ran in saying the Russians were occupying our country. I called after him that this was nonsense, that I understood politics.” Kouřil returned from military service in 1970 and the following year became a project architect with Metroprojekt.

In 1973 he joined the Union of Musicians’ Jazz Section. He started writing for the JAZZ bulletin, worked in the organisation’s administration and in the 1980s became secretary of Jazz Section’s committee. “Piles of letters would arrive. We gradually took in new people and in the end had over 6,000 rank and file members. Around 10,000 of them passed through Jazz Section.”

Between 1974 and 1981 he was involved in the organisation of the Prague Jazz Days festival. As a correspondent of Jazz Fórum, the magazine of the International Jazz Federation, he attended the Jazz Jamboree from 1977 until his passport was confiscated in 1984. Apart from a single visit to a jazz festival in East Berlin and a Chuck Berry concert in Budapest, these were his only foreign trips.

Though confrontation with the regime was slowly approaching, the Communists were not going to allow such a large and organised group, albeit one concerned with music, to act freely. “When the StB discovered that the Union of Musicians had no influence over us, they started dragging us in for questioning too. We held to the thesis that we weren’t doing anything illegal. I was interrogated but they never held me for more than 48 hours.” When the Union of Musicians was dissolved on orders from above in 1984 the Jazz Section also came to an end, legally speaking. However, it continued its activities as a collective member of the International Jazz Federation, which the state regarded as unlawful. This became the pretext for a trial of its members for “unauthorised enterprise”. The StB carried out two searches of Kouřil’s apartment, in 1985 and 1986. In both instances this was on 2 September and they seized everything linked to Jazz Section. He also lost the typewriter on which he copied samizdat texts for Jazz Section, the samizdat Lógr in Prague’s Hanspaulka and Infochy.

Kouřil, who had been a member of Jazz Section’s committee since 1980, was arrested with other functionaries on 2 September 1986. “I thought they’d let us be. Perestroika had begun in the USSR. But I was wrong.” He spent over eight months in custody. They tried to get him to confess to illicit enterprise during interrogations. His lawyer told him he wouldn’t be released, that it was a political decision. “When I got a 10-month sentence I only had a little left to serve. It was quite a relief.” He served his term in Bělušice and was released on 2 July 1987. Just before getting out he was placed in the Pankrác prison hospital with an acute kidney inflammation. His passport was not returned. Though he kept his job at Metroprojekt he was barred from leading his work group.

Along with other Jazz Section activists he wanted to renew the organisation so as to be able to hold musical events. This was denied. They tried founding a new group called Unijazz, which however did not receive a permit until the fall of the Communist regime. They regarded outwardly accommodating behaviour on the part of the Ministry of the Interior as intended mainly for Helsinki Process observers. Vladimír Kouřil also became a co-founder of the Prague organisation Artforum, which received a permit in June 1989. It came as a shock when, following the revolution, he discovered that the chairman of Jazz Section, Karel Srp, had been a long-term StB collaborator. “But Karel Srp was no longer in contact with us at that time. He had distanced himself from us. Those of us from the inner circle of Jazz Section are still a little traumatised by it.”

Vladimír Kouřil was rehabilitated by the courts in 1991. In 1990–1992 he was an editor at the post-revolution Melodie and headed the periodical Artforum. Since then he has written for many music and arts magazines, as well as for Czech Radio. Today he writes jazz articles and reviews for the magazines UNI, Harmonie and Hudební rozhledy as well as regularly organising playback evenings at Unijazz, where he still works as a project architect. He has written many books on music and a short story collection. In 2015 he received a certificate as a participant in the resistance and opposition to communism.

Text by Jan Horník