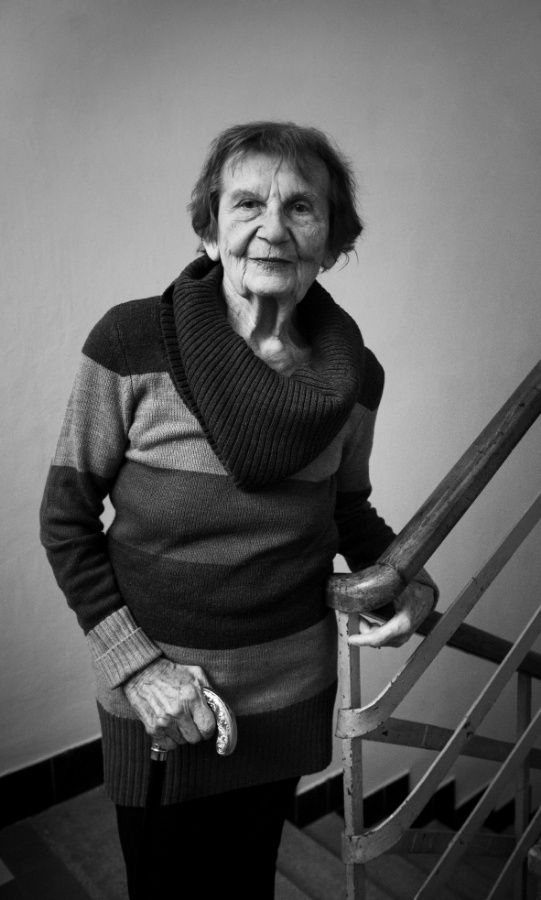

Marta LIČKOVÁ (*1926)

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

An indefatigable translator

The Russian writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn, a former labour camp inmate, revealed the horrors of Stalin’s Gulag to the world. For their part, the Slovak couple the Ličkos helped the world behind the Iron Curtain discover Solzhenitsyn. After his release they conducted one of the first interviews with him, which made a splash around the globe, and also smuggled his novel Cancer Ward to the West. In 1970 Solzhenitsyn received the Nobel Prize for Literature. And Pavel Ličko became one of the first political prisoners of nascent normalisation.

Marta Ličková was born in 1926, four years after her husband. The pair were joined by a love of literature and foreign languages. They also had a similar outlook on life. Marta was the daughter of an Evangelical cleric who died very early. She looked on in distress when the Hlinka Guard went on the rampage after the creation of the Slovak state, Czech professors were thrown out and her first Jewish classmates disappeared. Pavel took part in the Slovak National Uprising.

At that time Marta was doing her first tentative translations. It was then that she and Pavel first met. Alongside school English and Latin, both learned Russian to a high level. This was not just out of a love of the language. They both were fond of Russia but, they said, not many people knew its true face at that time. “It took a while for one to arrive at this,” said Marta Ličková, recalling that many people only gradually began opening their eyes when the Communists took power in Czechoslovakia. They too were disabused of their initial ideals.

However, there was a thawing in the 1960s. Marta and her husband had a keen interest in the information that gradually reached them from Communist Russia. When Khrushchev came to power he permitted the publication of books critical of Stalin and his cult of personality. At this time the inconspicuous physics teacher and ex-Gulag prisoner Alexander Solzhenitsyn was also allowed a voice. His first novel about the camps One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich was published in 1962. When Brezhnev took over he was barred from publishing but kept writing in secret.

“In our country One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich came out in Novy Mir. There was a lot of excitement that such a writer existed. We needed to track down the writer. But how? There was no contact information for him and we didn’t know how to get in touch with him,” says Marta Ličková. She contacted the Union of Soviet Writers on behalf of the magazine Slovenka, where she worked. At the Union they claimed he was unwell. However, they finally managed to get his address through friends. They entered into correspondence with the writer, who sent them a number of excerpts from his work that were published in Pravda. They had a strong wish to meet the mysterious author.

In the 1960s the magazine Kulturní život became a relative centre of freedom in Slovakia. Working there alongside such well-known journalists as Emo Bohúň, Agneša Kalinová, Juraj Špitzer and Roman Kaliský was Marta’s husband, the journalist and translator Pavel Ličko. When he and Rudolf Olšovský were sent on a work trip to Moscow, Ličko somehow managed to acquire permission to visit Ryazan, where Solzhenitsyn lived.

Following that visit, one of the first interviews with the Russian writer, exile and ex-Gulag prisoner was published in Kulturní život in 1967. “They picked it up abroad. It even got to Japan. And it paved his way to the world,” says Marta Ličková of the article, in which Solzhenitsyn spoke very candidly and openly about Stalin’s camps.

Pavel Ličko earned the trust of the writer, who gave him the manuscript of his new novel Cancer Ward, which he had hidden in his friend’s attic. “When my husband came home he said he’d given him the manuscript, telling him to treat it as he saw fit. Because Paľo had said to him: ‘You are aware that, if it remains here, you could end up in the camps again and nobody would ever get the thing out’,” recalls Marta Ličková. Pavel Ličko smuggled the manuscript out in his laundry. “Thank goodness they didn’t take it from him at the border. We had it copied and my sister immediately got one copy to translate.”

A second copy reached the UK. When the publisher Lord Nicholas Bethell read Ličko’s interview he paid the couple a visit in Czechoslovakia. “And because my husband also had Cancer Ward from Solzhenitsyn the subject of it being published in England came up.”

But first they wanted to meet Solzhenitsyn once more. After some time Pavel Ličko went to visit him again. “Things were difficult at that time. It was in a period when they had expelled him from the Union of Writers and he wasn’t allowed to give any public consent to the publication of his anti-Soviet books abroad. But because Paľo had that consent – ‘treat it as you see fit’ – he swore on the Bible in front of the publisher in London that he had that consent. And the book came out.” The contracts were drawn up in Solzhenitsyn’s name and the royalties were placed in a fund for him.

“Solzhenitsyn was glad at the time, because in those days he wasn’t so well-known.” In the meantime, a version of Cancer Ward, which had got out via the Russian security forces, was published in Italy. “Solzhenitsyn said it was a pirate publication. I don’t know how much it differed,” says Ličková. The real manuscript was in the hands of her and her husband and was the version that came out in England and spread around the world. In Czechoslovakia a translation of the book was not issued until after 1989. Hopes of change brought about by the relaxation of the 1960s had collapsed in the country.

In 1968 the Ličkos travelled to London in connection with Cancer Ward. It was August and everybody urged them not to return home but to remain in the UK with their children.

“Around a week before the occupation we returned home and everybody was saying they’d invade, that troops were already assembling. They had information to that end. So we said at home we’d think it over. But how would the Russians occupy us. We still didn’t believe it.” The invasion by Warsaw Pact troops came as a huge shock to them both.

Marta’s sister translated Cancer Ward very quickly, but it was no longer possible to bring it out in Czechoslovakia. At that time Marta translated a play by Solzhenitsyn that wasn’t published and was lost. “It was never found. They put the kibosh on it out of fear.” In September 1968, the couple, left-wing ideologically, quit the Communist Party. As Marta Ličková recalls, they soon realised that the mistakes of individuals were not the issue – the whole system was built on bad foundations.

Things went downhill for their family. In part because in 1969, when the borders were still open, Pavel Ličko had spoken unequivocally on Independent Television in London. “Yes, of course my country is occupied. And I will do everything to ensure Solzhenitsyn reaches the world.”

In 1970 Solzhenitsyn received the Nobel Prize for Literature. For his part, Pavel Ličko became one of the first political prisoners during nascent normalisation. He was inside for two years. “He said the worst thing was pre-trial detention. And then they put him in Ilava,” his wife says. Soon afterwards Marta ended up in hospital. With a lawyer’s help, they eventually got to see each other again at the end of the year.

“For several months we couldn’t even write to one another. But the lawyer organised a meeting for Christmas Day. And he warned me: ‘Please, you mustn’t cry, he has lost 20 kilos in four months so don’t let that knock you off your feet.’ It didn’t knock me off my feet, but it was terrible. In the presence of screws. The waiting room was jammed. Everybody together. There were thieves there, murderers too.” Her beloved translations were a help to Marta. “I did The House of the Dead when my husband was inside. I also wrote to him in letters. ‘I think I’m losing it.’ The concept of freedom and unfreedom is broken down so much in it, especially how a human being can become unfree. Suddenly you are placed at somebody’s mercy – it was terrible,” she says of the days when her husband was in prison.

The regime even made a propaganda film about them, Who is Lord Bethell, in which the Communists accused Pavel Ličko of being a Western spy. “It was dripping with pounds, money. Then they showed it on repeat. It was very successful. A well-known actor, Vladimír Müller, appeared in it. To this day I don’t understand how he got involved. He apologised a lot for that film. They must have put him under pressure, because he was a decent man.”

When her husband, his health broken, returned home, the State Security hauled Marta Ličková in for questioning. Both were to cease translating immediately. However, nobody would hire her husband, dubbed a British spy by the regime. Pavel couldn’t even find work in a boiler room. What’s more, his health had been destroyed in prison. Marta became the breadwinner, doing manual labour and translating at night, under somebody else’s name.

“My husband listened to all the world news. His only connection to the world was Radio Free Europe. ‘The whole behemoth has to fall some day,’ he tried to persuade me.” Pavel died on 26 November 1988, just a year before the regime did fall. This led Marta Ličková to experience the Velvet Revolution all the more keenly. “I was at all the demonstrations.”

Shortly after 1989 Cancer Ward came out in translation in Czechoslovakia for the first time. In the translation done by her sister in the pre-normalisation period, which had been saved. Ličková’s translation of Solzhenitsyn’s play was lost in the mists of time, though it has remained in her memory. Solzhenitsyn turned his back on the Ličkos at the end of his life, attaching himself to nationalist and anti-Semitic groups and Great Russia. But as we know, the glory of many of history’s greats is built on the stories of many nameless heroes.

After the fall of the regime Ličková was visited by Lord Bethell and remained in touch with their friend from London until his death. Today she regrets nothing – not even the tough times she and her husband endured. “Yes, it was difficult. But it should be said that it somehow worked out. You have to do your all and hopefully it will work out. For the most part it does.”

Text by Soňa Gyarfašová