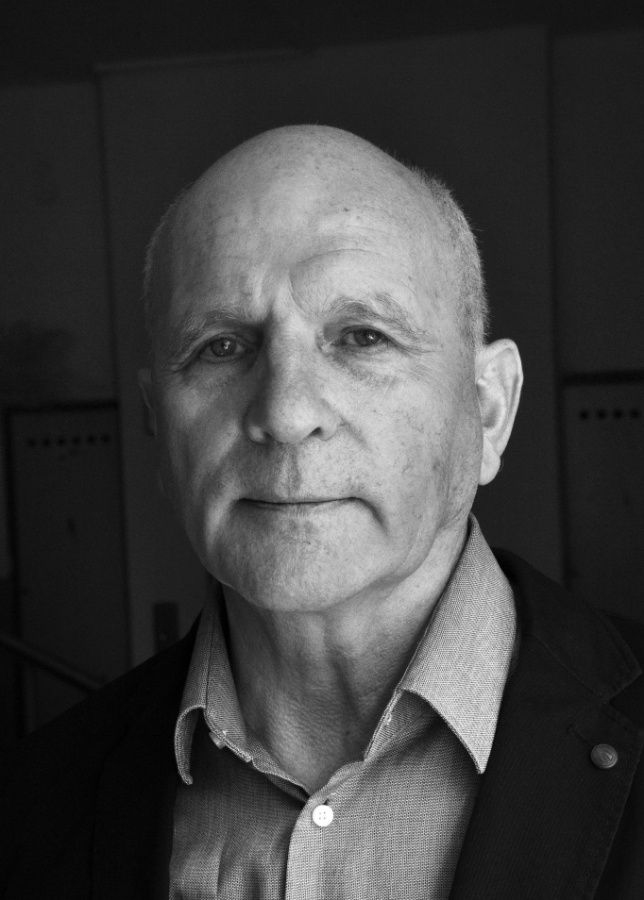

František MIKLOŠKO (*1947)

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

I tried to find myself and my own path every day

František Mikloško has entered the history books chiefly as one of the organisers of what became known as the Candle Demonstration in Bratislava in 1988. A significant protest against the totalitarian system, it was attended by thousands of people and violently quelled by the regime. This despite the fact it was a peaceful demonstration for religious and civil rights. “The impulse for the Candle Demonstration came from Slovaks abroad and from the former hockey international Marian Šťastný. Protest gatherings advocating adherence to human rights and religious freedoms were planned in front of Czechoslovak embassies around the world and we also received a call to take part… I passed on that request to the secret church, so we accepted the idea and gave it our own content, stemming from current requirements here in Slovakia and in Czechoslovakia. Not delivering speeches but holding lit candles,” recalls František Mikloško. At that time he was a dissident, an ordinary worker despite having graduated in mathematics and previously having attended the Institute of Technical Cybernetics at the Slovak Academy of Sciences. The demonstration was a harbinger of the fall of the regime and Mikloško later enjoyed a successful political career as a deputy of the Slovak National Council and later the National Council of the Slovak Republic. “The hardest thing was finding myself and my own path. I had to try to do that every day.”

František Mikloško was born in Nitra in 1947 into a family in which faith was paramount. His mother taught French and Slovak at a grammar school. “She was from the first generation of educated Slovak women. She had studied in Bratislava and lived in Nitra. And I grew up in a certain environment from the beginning and then my whole life. I experienced a home search as a three-year-old in 1950. And more in 1960. The search was for religious literature. Mum was repeatedly interrogated,” Mikloško says.

Religion was naturally part of his life from childhood on. “Thanks to mother, I inherited a joyous faith, so I never had a crisis of faith. It was and remains an absolute point of support that I can’t imagine any of my decisions without. It really liberates me – it makes me free.”

Mikloško decided to study mathematics at the Faculty of Science at Comenius University in Bratislava. He arrived in the city in 1966, when the atmosphere in the Communist Party-controlled country was beginning to become freer. Less than a year later he met Vladimír Jukl, a Roman Catholic priest who had spent 14 years in prison and was released in 1965. Mikloško confesses that Jukl had a major influence on him. At that time Jukl was setting up secret church university groups in Slovakia. “Thanks to him I also got to know Bishop Ján Korec. I was active in that world until 1989, organising unofficial gatherings of young Catholics, the production of samizdat, the relaying of reports abroad and suchlike. I kept getting more involved in the dissident scene,” says Mikloško.

Other new acquaintances were made in the civic dissent, represented by, for instance, the philosopher Miroslav Kusý, Ján Budaj and Milan Šimečka. He also got to know the Czech dissidents Václav Malý, a priest, and Václav Benda.

“One specific moment was important for me, when I became involved in the secret church in the time of the dissent. I was deciding at that time whether to secretly go for the priesthood and become a clandestine priest, or to be active as a lay person. Life showed that I didn’t become a priest and that’s how it was meant to be.”

However, his faith did help him in the 1970s and 1980s, when he succeeded in overcoming his fears of Communist repression. “I knew that the faith was something worth going to prison for and that it wasn’t a waste of time,” he says.

From his perspective he was lucky to be able to live so close to such figures as Vladimír Jukl and Silvester Krčméry, another underground church organiser who also experienced lengthy imprisonment. When normalisation began Mikloško was a mathematician doing basic research at the Slovak Academy of Sciences. “I discovered that the roots of mathematical problems were close to beauty, aesthetics and, I would say, poetry. I regarded mathematics as part of beauty and that didn’t impede my path to faith,” he says. However, in 1983 he decided to radically overhaul his life and began doing manual work, on the railways and in construction as a stoker. At this time, though, the dissent was his main environment. The secret police also took an interest in his activities and constantly called him in for interrogation. By this time, however, many sensed that the Communist regime wouldn’t last much longer. “At the end of the 1980s we in the secret church were interested in visions somewhat and we were particularly taken with the visions of the Salesians of Don Bosco, who had a dream that the Virgin Mary would perform a great world miracle a century after his death at the latest. Bosco died in 1888, so as the year 1988 approached we were filled with anticipation of the fall of communism,” says Mikloško.

In those days he agreed fully with the view of Ján Čarnogurský, who insisted that the struggle against communism was total and was waged by every nation using that which was essential to it. In the Czech lands, for instance, that was intellectual life; in Slovakia, it was popular Catholicism.

In the end, however, the speed with which the regime fell in November 1989 surprised him. Mikloško's political career was also marked by speed. As early as November 1989 he became a member of the Coordinating Committee of Slovakia’s Public Against Violence, on whose ticket he was elected to the Slovak National Council in 1990. He was elected speaker the same year, occupying the post for two years. In the end he served as a deputy in the Slovak National Council and later the National Council of the Slovak Republic without interruption from 1990 until 2010. A full 20 years. However, he always tried to maintain a sober outlook. “I regret my weaknesses, but I take them as a part of life that has led me to humility,” says Mikloško.

Text by Luděk Navara