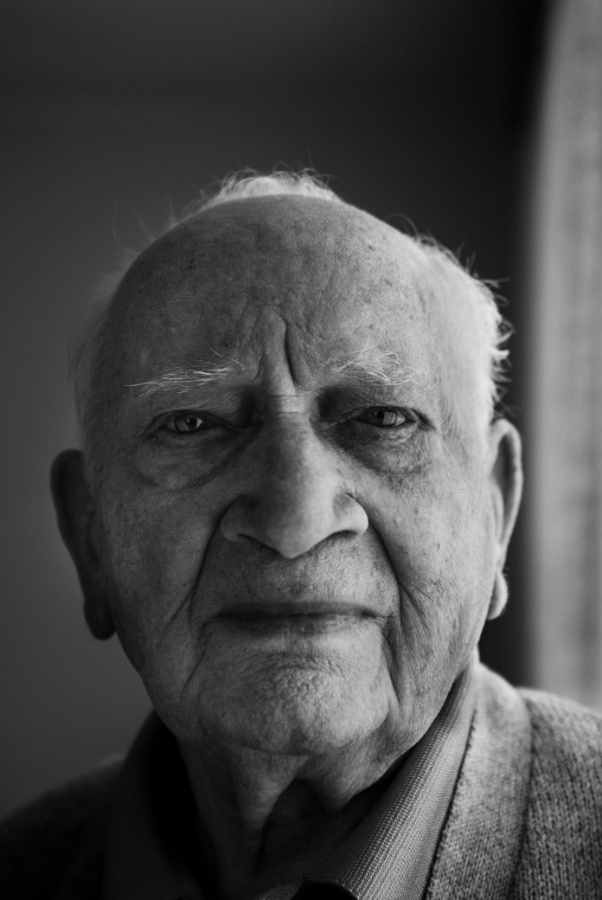

Ján ZEMAN (*1923)

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

The worst thing was the thought that my wife would pay for my actions

“I’m proud of the fact that we managed to keep it together during interrogations and didn’t show them weakness,” says Ján Zeman from Myjava in Slovakia, who was facing the severest punishment: hanging. The fact his wife had been arrested with him compounded his anguish. “The hardest thing was the thought that they would abuse my wife in some way during interrogations at the StB. They’d threatened as much. The psychological pressure was far worse than the beatings.” Ján Zeman hadn’t wished to keep any secrets from his wife. They had agreed not to at the outset of their relationship. She therefore knew about his espionage work, and had even helped him to encrypt reports.

Ján Zeman worked at the construction section of the Povážské engineering works in Myjava, where the output included weapons. His reports were highly valuable. “I gave them a plan of the plant. I marked individual buildings on it, what was produced where, where the People’s Militia arms store was, the number of militia men at the plant and how many guns were produced…” He relayed messages via dead drops, bringing them to agreed spots with his wife, who kept lookout. He was arrested in August 1949, tortured and threatened. In the trial of Ján Zeman et al. at the state court in Bratislava he was sentenced to death and the seizure of his property. Following the intercession of the United States Embassy a Communist court commuted the sentence to life imprisonment.

Ján Zeman was born in Myjava in Western Slovakia in 1923. His parents moved to the US before the war. Zeman regarded himself as a Czechoslovak patriot. He studied at an engineering-focused vocational school before finding work as chief design engineer at the Povážské engineering works in Myjava, where weapons were produced. A network of armaments factories had sprung up around the Czech-Slovak border shortly before the war. Naturally this was of interest to Western intelligence services once the Iron Curtain had been put in place. In early March 1949 Zeman was contacted by courier Štěpán Gavenda of František Bogataj’s intelligence group. He was naturally keen to collaborate. After seeing the Communists liquidate Slovak Democratic Party representatives he observed a wave of forced collectivisation in which farms were turned into cooperatives. The Slovaks had a strong attachment to the land, so this led to tragedies, including suicides. Nationalisation also occurred. People could see the Communists had come to power despite being incompetent. That was the case at the plant in Myjava where Zeman worked, which had just begun the production of detonators for hand grenades. However, Western agencies were interested in all kinds of information. One thing Zeman passed on was information about the repression of Catholics. The espionage he agreed to carry out seemed at first glance relatively safe. Encrypted reports were to be transferred via a dead drop located above the town, beneath a simple wooden triangulation tower. The reports were placed inside a hidden jar. He had received instructions on how to construct the dead drop from Bogataj. In total he relayed five reports, each of which his wife also worked on. “We went there during the day. I selected the dead drop box and she kept lookout. We tried to choose the boxes in such a way as not to be suspicious,” he said later.

However, Zeman’s colleagues were not always so vigilant. “There were a lot of deficiencies in that organisation. When a courier crossed the Iron Curtain from Germany they already knew about it in Prague,” he said. What’s more, the agent who collected from the dead drop outside Myjava used to pay the Zemans regular social calls. “He should never have come to my place. He should have created the dead drop and then never shown up again. But he visited us as an acquaintance and my wife provided him with hospitality. He collected the dead drop and came. And began coming regularly.” The man, who had a reputation for fearlessness, later entered the history books as one of the most active couriers. He was twice sentenced to death and one time managed to break out of Leopoldov prison, from which escape was said to be impossible. In the end Gavenda was executed in Prague in 1954.

“Gavenda had a kind of military bearing, which I liked. He really engendered trust. He didn’t come across as an adventurer. Initially he brought a letter. I opened it and there was a letter from Bogataj. I knew the name from ‘Carbon’, so I had trust,” said Zeman.

In any event, Zeman was soon caught. “On 3 August 1949, in the early evening hours, the arrest was made of Ján Zeman (…) address Myjava, employed as a technical official, married, nationality Slovak, who was connected to agents of the American intelligence services, for which he acquired reports of an economic and political nature,” reads a report dated 5 August 1949 on Ján Zeman’s preliminary testimony. Zeman himself offers this description: “Two of them came to my apartment. They said they were arresting me and that I was to go with them to Bratislava. It was some time in the evening or early evening. I had a hunch but it wasn’t possible to escape – both were armed.” Zeman underwent brutal torture. What’s more he feared for his wife, who’d also been arrested. “There was a tiled floor there. I couldn’t even lie down and had to keep walking, shining the floor. Then the StB started the interrogations… beatings with a pistol to the head, to the feet. It was beating session. Then a very well-dressed man entered and said there was no point denying anything, Gavenda had told all. So I realised that Gavenda must have been caught.”

The entire time Zeman was worried about his wife, who later received a term of 14 years, eight of which she served. “The fact they threatened her was the worst thing. They said they’d make a prostitute out of her and I had no doubt they’d carry that out.”

There were other real or alleged spies in the group that the Communist regime put on trial, not all of whom knew one another. Alongside Zeman and his wife, these included Viliam Šimko, his wife Emília, Pavel Kusenda, Jaroslav Škoula, Ondrej Pavella, Mojmír Freund, Martin Kavický and Štěpán Gavenda. They were sentenced on 7 October 1949. Ján Zeman received the death penalty, at the urging of then prosecutor Anton Rašla. However, he avoided the gallows. He was probably helped by relatives in the US, as the American Embassy interceded on his behalf. In September 1950 his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment.

“I don’t regret what happened. I regard all the things I did as my civic duty,” he said later. “Fourteen and a half years in jail at a young age was a major loss. But neither I nor my wife regretted it. I’m sad today. I was born in Czechoslovakia and I’ll die a Czechoslovak…” Ján Zeman has a disappointed tone but is still satisfied with his own life. Despite all he has been through, including the labour camps at Jáchymov and Příbram and living for a year with the expectation he would be executed. “Life is a hike around a mountain peak. The higher you are, the greater the view you have. The more you progress in life, the better you appreciate what has come before.”

Text by Luděk Navara