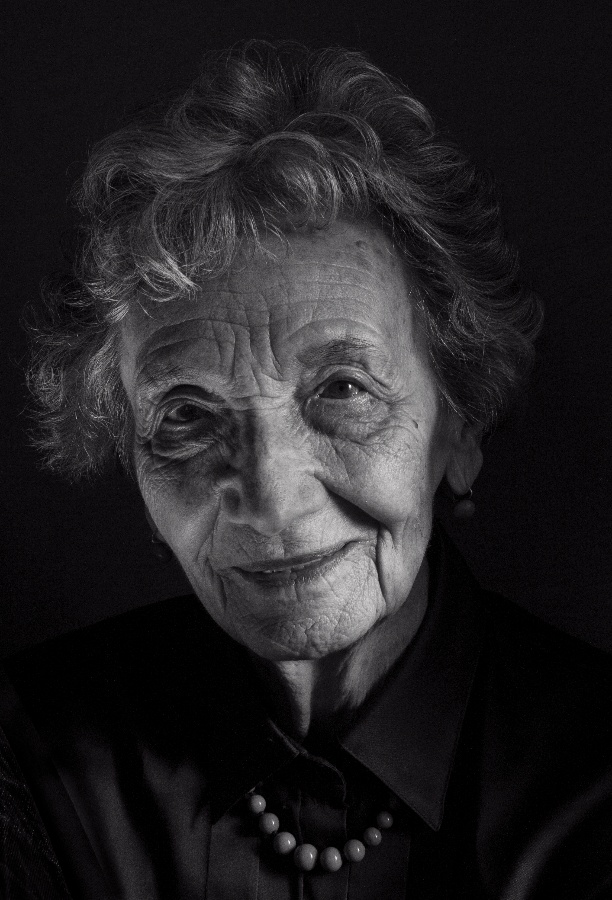

Miluška HAVLŮJOVÁ (*1929)

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Get that brat out of here

On 26 May 1953 the home of the Pompl and Havlůj families in Rudná u Prahy was visited by officers of the Communist State Security. They arrested 24-year-old Miluška Havlůjová, whom they had first ripped away from her small son, and carted her off to “HQ” on Bartolomějská St., leaving here in a cell there for several days. More than half a century later, Mrs. Havlůjová recalls the scene: “Then one day they took me off to an interrogation centre. There they hung my clothes on a hook and an StB supervisor said: ‘Go look out the window!’ A woman with a pram was walking along the pavement and in the pram was a child the same age as my child at home. It was probably the worst moment of my life. In that moment I began to pray and said: Dear God, help, help me. And suddenly it was clear to me that I couldn’t sign up to cooperate. It was as if God had suddenly stood beside me, as if he gave me a helping hand. I told that StB man that I wouldn’t sign. They packed up and sent me to solitary.” Signing the cooperation papers meant becoming an informer. The StB’s idea was to have Miluška testify against her father. Refusing meant remaining in prison. Without her son.

Miluška Havlůjová was born to Emilie and Jaroslav Pompl on 13 May 1929 in what is today Rudná u Prahy. However, she and her brother grew up in the Brdy foothills in Rožmitál pod Třemšínem and the nearby Voltuš, where her grandfather had bought a sawmill and built a house. The Pompls were living there in March 1939 when the Germans occupied Czechoslovakia and they soon joined the anti-Nazi resistance. Jaroslav the father co-founded the Rožmitál “branch” of the underground organisation Obrana národa (Defence of the Nation) and later played a central role in the hiding of around 50 refugees; in the main Red Army soldiers who had escaped captivity found temporary shelter there in forest bunkers built and supplied by the resisters.

In the autumn of 1944 an informer betrayed the Třemšín resistance group. Some of the members were killed during Gestapo raids, but Jaroslav Pompl hid with friends in time. Though the Germans were offering a reward of 10,000 Reich marks for his capture, he managed to evade them until the end of the occupation. His wife Emilie was held at the prison in the Small Fortress at Terezín, where she contracted typhus that may have saved her life as the Nazi officials didn’t manage to put her on trial. In those days Miluška was living with her brother at their grandparents’ in Rudná. She recounts: “When father went underground the Gestapo searched for him vigorously… the Nazis came in the night and knocked on the windows and doors at two or three in the morning. We all had to stand in our night wear in the corridor. In the meantime, they crept through the building… those Gestapo leather coats – they’re one of my nightmares.”

Following the defeat of Nazism, the Pompls happily met up and Jaroslav received an honour: the Czechoslovak 1939 War Cross. At the end of the occupation Miluška had managed to take part in the Prague Uprising. She later attended grammar school and prepared for her leaving exams, which she passed in 1948. However by then the family had fresh problems. Jaroslav Pompl was a democrat who had no truck with the ideas or the practices of the powerful Communist Party and looked askance at those who played up their resistance activities or attempted to make a career via their party card. In addition, he had no illusions about the Soviet Union; he had heard enough from the soldiers in hiding to have a clearer picture of Stalinism and didn’t disguise his scepticism about the pro-Soviet direction of Czechoslovak politics.

The Communists dealt with this “unadaptable resister” immediately after the party’s coup d’etat of February 1948. The Pompls were dubbed class enemies and the state stole their company (the sawmill in Voltuš) and other property. On 21 December 1948 Jaroslav Pompl was arrested and charged, absurdly, with collaborating with the Germans. A people’s court in Písek sentenced him to a year’s forced labour in a limestone quarry. At this time Miluška learned she was barred from studying and that under an official order she had been “assigned to work” feeding cattle. She tried to find other work in Prague and was accepted as a model by textile enterprise Textilní tvorba; this was one of the few places inquiries were not made about one’s family origins and political profile.

Jaroslav Pompl returned from prison at the end of 1949. He was greatly pained by his unjust conviction and wished to clear his name. He petitioned for the renewal of his trial, but in vain. He then wrote a report on his case and Czechoslovak labour camps, hoping to get this testimony about conditions in the country to the West. He asked his daughter for help. As a model, Miluška knew the hairdresser Oldřich Trávníček, whose clients included ladies from the embassies of democratic states. She brought him her father’s papers and the hairdresser promised to hand them to trustworthy diplomats. This he never did, at least according to subsequent StB reports that record his willing testimony.

In 1950 Miluška Pomplová married Miroslav Havlůj and a year later gave birth to a son, Tomáš. A few months later the secret police began to again monitor her father, who was in contact with other people persecuted by the regime. On 21 January 1953 Jaroslav Pompl was arrested for the second time. Soon it was his daughter’s turn. The StB first picked up Miluška and her young son on the street and took her to an interrogation centre. “I had Tomáš on my lap. They began interrogating me. They asked what father had done with the files from his trial… Then they began to shout at me, asking about some people, but I didn’t know them. Their shouting caused Tomáš to start crying and one of the StB men shouted: ‘Get that brat out of here!’ They took Tomáš out of my arms and took him outside the door, to some closet… They kept interrogating me… In the meantime, he was crying, then he fell asleep and woke again, called out and again cried… He remained locked up for around four hours.”

The investigators released Miluška Havlůjová then. However, they continued to watch her and occasionally brought her in for interrogation. On 26 May 1953 she was arrested again – and the blackmail described in the introduction began. As she had refused to inform on her father and his friends she remained in custody for five months. On 27 November 1953 she was convicted in a show trial for “attempted sedition against the republic” and “attempted espionage” to five years of hard prison, the seizure off all her property and the loss of her civic rights for five years. Her father Jaroslav Pompl was convicted on 15 December 1953. He got 10 years in prison.

Due to poor health, Miluška Havlůjová was placed in April 1954 in a prison in Svatý Jan pod Skalou, where she mainly worked in the prison hospital. She contracted tuberculosis and didn’t recover for some years. She was released early on, 1 March 1955. However, following her release her relationship with her son, who had been living with his father and grandmother Emilie Pompolová, was complicated. Winning the boy’s trust was slow and difficult. In subsequent years she made a living as a clerk and accountant. In 1989, when communism was collapsing, she was active in the Civic Forum. She later became a local councilor and in the end mayor of Rudná, where she lives to this day. Her father got out of jail in 1960 and died in Voltuš five years later. Her brother Karel was forced to join the army’s Auxiliary Technical Battalion for the political unreliable and later worked in the uranium mines. He died prematurely, at the age of 61.

Text by Adam Drda