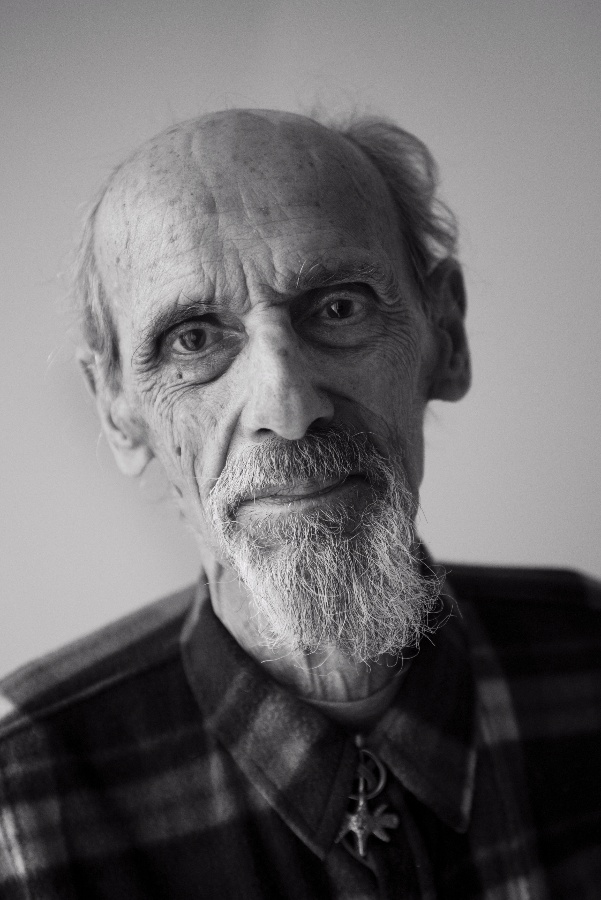

Ivan KIESLINGER (*1928)

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

A man intended for liquidation

Ivan Kieslinger was born in Prague, on 28 October 1928, into the family of a bank clerk. As a boy of 10 he joined a scout troop, where he was nicknamed Oxygen. Following the Nazi occupation of 1939 the authorities banned scouting. By then Ivan was deeply committed to it. His troop continued in secret and, though its leader objected, the boys began to “do resistance”: they carried reports, observed and recorded train movements and identified spots suitable for sabotage. This was not enough for Ivan. At a most inopportune moment – the end of May 1942, three days after the attack on Reinhard Heydrich – he attempted, on his own, to produce explosives, carrying out experiments using chemicals commonly available in shops. However, he was not quite 14 years old and as a chemist possessed more fervor than experience. He lit a test fuse, causing a spark to enter an unprotected glass containing a compound. An explosion followed that maimed his hands. Not wishing to frighten his parents, he went to a doctor alone. A total of three doctors refused to treat him without police involvement. In an atmosphere of universal fear, and as the terror sparked by Heydrich’s death began to intensify, they feared punishment. So Ivan went to a gendarmerie station with the made-up story that he’d fallen from a rock and injured himself on sharp stones. Fortunately they believed him.

In 1944 he acquired a duplicating machine, which he used to print a scout anti-occupation magazine. In the first months of 1945 he took part in a weapons drop mission for the resistance in Brdy and in May 1945 “served” in the Prague Uprising: “A tank came up to where we were. I had been sent to Wenceslas Square – and I was supposed to shoot at it with a bazooka if it got close. I hid in the toilets and a friend gave me a signal. He was standing on the corner (…) and in his hand he had a large mirror via which he observed the machine. The Germans in the tank evidently didn’t have a sense of humour and shot the mirror out of his hands. Nothing happened to my friend. But I never saw such a change in a face in my life. He went utterly pale.” In the end the tank turned around and disappeared. Ivan recalls the end of the occupation with a smile: “Toward the evening janitors just poured out and started sweeping up the glass. That meant it was all over. The war had ended.” A few years later he wrote an account of what he had done in the uprising, concluding with these words: “For my activities in the revolution, I was decorated with a medal ‘for bravery’. It was stolen from me during my arrest by the State Security in 1948 and never returned.”

Following the Communist coup of February 1948 Ivan Kieslinger managed to graduate from grammar school and applied to the Czech Technical University. However, he was barred from studying for political reasons: he was a scout and a non-Communist and received a poor appraisal from the Communist Youth. He began earning a living as a labourer and soon became involved in student anti-Communist activities: “My friend Zdeněk Balvín, who was aware of my views, brought me the magazine Svobodný zítřek [Free Tomorrow], kind of leftist samizdat. It had democratic articles (…) written in a young, student spirit but also with rather serious arguments that following one, Hitler-led, form of violence another was coming that was little different. So I just circulated it.” However, the secret police (State Security/Státní bezpečnost, StB) had an informer in the group. On 10 October Ivan left for Sušice, where at that time he had his official address (his father was from there), so he could enter military service. It was then that he was arrested for the first time and brought to an StB interrogation centre in Prague: “At first the interrogation struck me as tough. However, compared to what I experienced later, it was a walk in the park. They shouted and slapped me… They knew it all anyway.” In court Ivan Kieslinger received a six-month sentence, which he served in part at Prague’s Pankrác prison and in part at the Mejrovka mine at Vinařice near Kladno. He was released on 12 April 1949.

A few days after his release – when he had found work as an assistant chemist – the scout leader and future political prisoner Dagmar Skálová contacted Ivan, asking whether as a former political prisoner he knew the precise whereabouts at Pankrác of the imprisoned General Karel Kutlvašr, the commander of the Prague Uprising. As he did know, Dagmar Skálová asked his help. She told him an anti-Communist coup was in the offing and asked him to navigate the group that would free Kutlvašr and other prisoners. Though Ivan had just returned from prison, he agreed. Skálová then set up a meeting between him and one of the operation’s organisers, Emanuel Čančík: “We agreed to meet on the night of 17 May, when the uprising was meant to break out – and that 40 men with machine guns would be available. The planned uprising was meant to have army involvement (…). A full day before it I sensed something wasn’t right, because beefed up patrols appeared in the streets (…). I called Skálová. Čančík was at her place. I told him: ‘There’s no way an uprising can go ahead today. Everything has evidently been betrayed…’ He replied: ‘We’ve postponed it twice – there can’t be another postponement.’”

The attempted coup, which involved tens of people, remains murky to this day. Through its collaborators, the StB likely controlled it from the start or even initiated. They were trying to uncover and lock up democrats who were most strongly opposed to communism and willing to resist, such as Ivan and Dagmar Skálová. On 17 May Kieslinger made his way to a planned meeting. However, he was unable to reach anybody. He was arrested on 24 May 1949 and found himself at an StB interrogation centre. Later he learned he had been uncovered when the police intercepted a call he made to Skálová’s. This time the interrogations were tougher. “I had a wet towel on my head the whole time. Then they pointed a sharp lamp toward me. It dried the towel so it contracted and it hurt… they kicked and beat me… The interrogations always lasted several hours… They mainly wanted to know who I was in contact with… They had nothing on me, only Čančík’s statement. He was really excellent (…), he was tough and didn’t give away what he didn’t have to.” Ivan Kieslinger was sentenced to 16 years in prison under the “pliant” law no. 203 (on defence of the country). His punishment also included a fine of 20,000 crowns, the “loss of honour” for 10 years and property confiscation.

After a short stay at Bory prison in Plzeň and Ostrov, Ivan was sent to the uranium labour camps in Jáchymov. There he became a MUKL (Muž Určený K Likvidaci, man intended for liquidation). He was assigned to a mine but more than the slave labour for the Soviet Union (where all the uranium went) he was suffered due to bugs and a lack of water. In December 1949 he became ill and ended up at the sick-bay: “It was Stalin’s birthday and on that account the wardens carried out a major barracks inspection. We had to enter the corridor. When the inspection ended they pulled me out and brought me to the guardhouse. (…) Later they said that radioactive uranium had been found in my bed, which was barred and punished harshly. (…). But I hadn’t taken any active material. They beat me for the whole shift, around eight or 10 hours. They trained on me, showing how slaps should be delivered correctly (…). I had bare feet and they my feet (…). I could barely see. In the end they threw me into correction.” Correction (solitary confinement) was in an unheated wooden building. It was December in the Ore Mountains. Kieslinger moved in and out of consciousness and remained in the “hole” during Christmas.

From solitary at Rovnost they escorted him to the Mariánská labour camp. He was due to go back down the mine in the New Year, but he had a nervous collapse: “Then my feet started to hurt. Once I woke up in the night and lost consciousness because of the pain. The next day I went to work and all of a sudden keeled over. I started to have a fit: uncontrollable twitching in my right hand, terrible pain and then loss of consciousness. At the infirmary a doctor said I had epilepsy.” After this diagnosis the scout Oxygen, black and blue, was sent to Valdice. “The doctor discovered that it was so-called Jackson’s epilepsy (…). There was a blood clot on my brain (resulting from beatings) that caused fits.”

A pain in Ivan’s hip kept getting worse and he gradually began to limp. The doctor said he had also contracted tuberculosis of the bones. He was moved to a so-called muklheim, a home for dying prisoners. He ceased moving and went to the prison infirmary. However, his mother, who tirelessly wrote requests for his release, had to find his medicines. “For about two years they carried me on a stretcher (…). Later I began walking on crutches (…). I remained until 1954, when they abrogated my sentence so a civilian hospital could ascertain the outlook for me. When they learned I’d never work again I received a pardon.”

Ivan Kieslinger had epileptic fits until the 1970s. For long years after his release he was beset by difficulties. For 10 years he had no civil rights. When he somehow got into university he was soon kicked out. Until 1968 he worked as a labourer at engineering firm ČKD. Following the Soviet invasion he worked as a chemist, although with strict political restrictions, naturally. During normalisation he was again active in the banned scouts. In 1990–1991 he was rehabilitated. Today he lives alternately in Prague and Sušice, in a building with a symbol of a ship where his predecessors had an ironmongers and the U Šífu pub. He is actively involved in the Confederation of Prisoners, where he is in charge of social care.

Text by Adam Drda