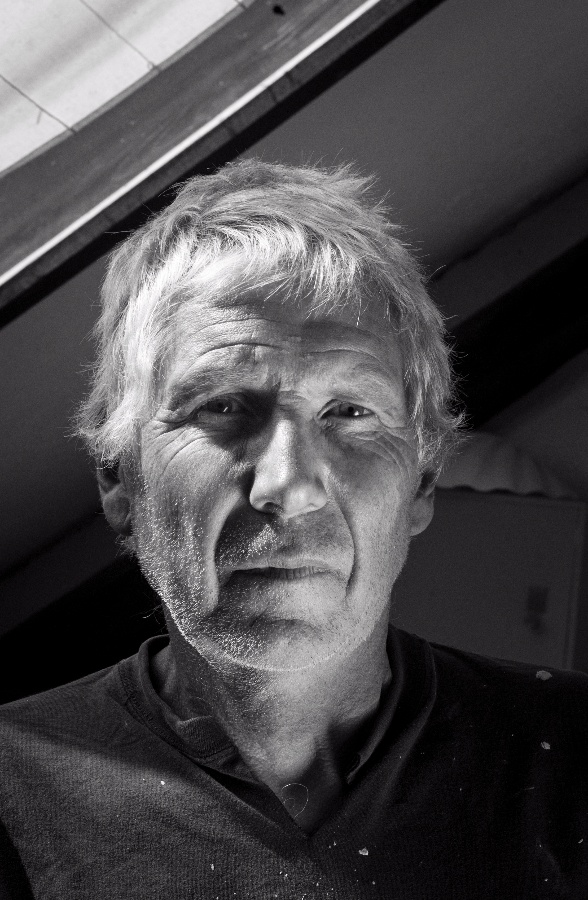

Otmar OLIVA (*1952)

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

I saw that people of my generation jumped willingly into the Bolsheviks’ embrace

He remembers the moment perfectly. On 17 October 1979 they arrested him. It was 9 am. At the time he was doing his military service. And his wedding was in two weeks. “Of course they knew that, because I had requested leave for the wedding… They put two other soldiers on me, agents who informed to the military counterintelligence. They charged me with incitement and distributing Charter 77 materials,” Oliva said. He was imprisoned for 20 months. It was the test of a life-time. The worst thing in prison was the cold. Oliva says he found God during his time behind bars. He also managed to capture this trying period in drawings. His attorney Josef Krupauer offered to smuggle them out. But how? They wondered whether it would be at all possible. Oliva watched out to see which of the wardens was carrying out thorough searches of prisoners. He noticed that one never touched them on the belly. “So I put it on my belly and it got out. Josef Krupauer then saved the drawings. There were a lot of them. I drew two blocks there. Sixty drawings perhaps,” Oliva says. The lawyer then gave them to Oliva’s intended, Olga. “For her, for her it was actually the worst,” Oliva adds.

However, he learned from his fellow inmates that it was possible to cope even in prison. One of them, for instance, listened to the banned Voice of America. He had a radio in a soap box. He got the batteries from the accounts office, where they were used in calculators.

Otmar Oliva refused to be cowed and following his release from prison behaved like a free man. He moved to Velehrad in the Uherské Hradiště area and focused on his art. He pushed for the things he regarded as important and established contact with people who shared his attitude to the Communist regime. He produced art. Today he is a recognised sculptor both in the Czech Republic and internationally.

Otmar Oliva was born on 19 February 1952 in Olomouc. He grew up in Hodolany, a quiet suburb of Olomouc not far from the city centre. His outlook was shaped significantly by his father, who was a soldier and member of the anti-Nazi resistance. He fought in the West, which, as was typical, led the Communists after their takeover of February 1948 to automatically regard him as untrustworthy. And more. For the Communist regime, each such “Westerner” was a potential threat.

His father was also called Otmar. During the war he had been an officer in the Czechoslovak Armoured Brigade, which was commanded by Alois Liška and took part in the siege of Dunkirk; though the town was surrounded it was controlled by the German army. In 1945 Otmar Oliva Sr. returned in uniform to Czechoslovakia as a liberator.

Following the Communist coup he was in the sights of the secret police. His son was nine when Otmar Oliva Sr. was arrested. “I was present for his arrest. I was going to third or fourth class. I remember the atmosphere and the behaviour of the teachers. They asked me where my father was,” Otmar Oliva Jr. recalls.

Following his father’s arrest a broken framed photograph of Field Marshal Montgomery, the commander of the UK’s 21st Army Group, lay on the ground, trampled on. However, not everybody behaved shoddily or overly cautiously. Oliva remembers one teacher who subtly attempted to help him at that time. “He was a fantastic teacher. He asked me to do him a kind of favour. Next door there was a fruit and vegetable shop and he asked me bring budgie feed to his place, saying that he bred them. He was trying to take my mind off things…”

When, later, his father came home from prison he tried to make those lost years up to his son. “We went on cycling trips, for instance to the Tatras. It was fantastic. After his release he wanted to give everything back to me that way,” Oliva says.

In 1967 he started studying at the Central School of Applied Arts in Uherské Hradiště. But then 1968 came. First liberalisation but then Soviet occupation and the emigration of his father, who left for Switzerland. The son continued his studies at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague. In 1978 he was lucky enough to experience a study stay in Greece. At the same time, dissatisfaction with the Communist regime was making itself felt. “We observed how our generation was broken. We saw how people jumped willingly into the Bolsheviks’ embrace. For instance, an StB man who was the same age as me. By becoming an StB man he was choosing the easy path,” Oliva says.

Involvement with activities surrounding Charter 77 followed, succeeded by enrolment in military service and arrest. And imprisonment. As a political prisoner he naturally had trouble finding a decent job after his release, so he decorated bells and worked with the Dytrychový bell workshop at Brodek u Přerova.

Naturally he didn’t get to see his father. “I was annoyed. Every year I applied to be allowed visit my father. I’ve got piles of rejections. I knew that’s how it was. But I knew I still had to do something,” Oliva says.

“The controlling organs of the National Security Corp’s passports and visas directorate has under its jurisdiction obtained your submission of 23. 2. 1986 under which you appeal to the president of the CSSR with an application for help in the matter of permission to travel to Switzerland to see your father, who has resided abroad since 1968 without the permission of the Czechoslovak authorities. With regard to your submission, I inform you that following an assessment of all the circumstances of the case your request has not been met,” reads a letter from the passports and visas authority dated 14 April 1986.

In the mid-1980s Oliva succeeded in setting up a foundry at his studio in Velehrad. The Refugium Velehrad Society of Friends met there when sculptures were being cast. They organised exhibitions and published in samizdat, meaning secretly copied books. However, Oliva naturally remained constantly under the watchful eye of the secret police. They accused him of having anti-communist attitudes and condemned his contacts with Catholic Church figures and other Christians. The StB had, incidentally, been monitoring many of them for some time.

On 30 November 2015 the Ministry of Defence issued a certificate stating that Otmar Oliva had been a participant in the resistance and opposition to communism in the period of repression. The substantiation referred to his “long-term and systematic work comprising, in particular, involvement in the publication, print and distribution of a samizdat magazine, a Moravian version of Střední Evropy [Central Europe], and other illegal printed materials of an anti-communist nature focused on the restoration of freedom and democracy in the then Czechoslovakia.”

Though Otmar Oliva had faced Communist totalitarianism, it had not managed to prevent him from producing art. He had first worked with the academic painter Vladimír Vaculka, though he had died prematurely in 1977. He had been hounded by the Communist regime and died as the result of a heart attack. A search of his home had been conducted shortly before his death. Somebody had evidently informed on him for illustrating a samizdat poetry collection by Jan Skácel.

Otmar Oliva was more fortunate. He became famous as a multitalented artist, producing numerous artefacts, bell decorations, liturgical items, medals, tombstones, memorials and memorial plaques and fountains, as well as conceiving complete art projects. Three years after the fall of communism he visited Rome and soon afterwards began working for the Vatican. He decorated John Paul II’s Redemptoris Mater Chapel. It includes the first papal throne made since Bernini’s time. Oliva also designed medals marking the 20th anniversary of the start of John Paul II’s pontificate.

Text by Luděk Navara