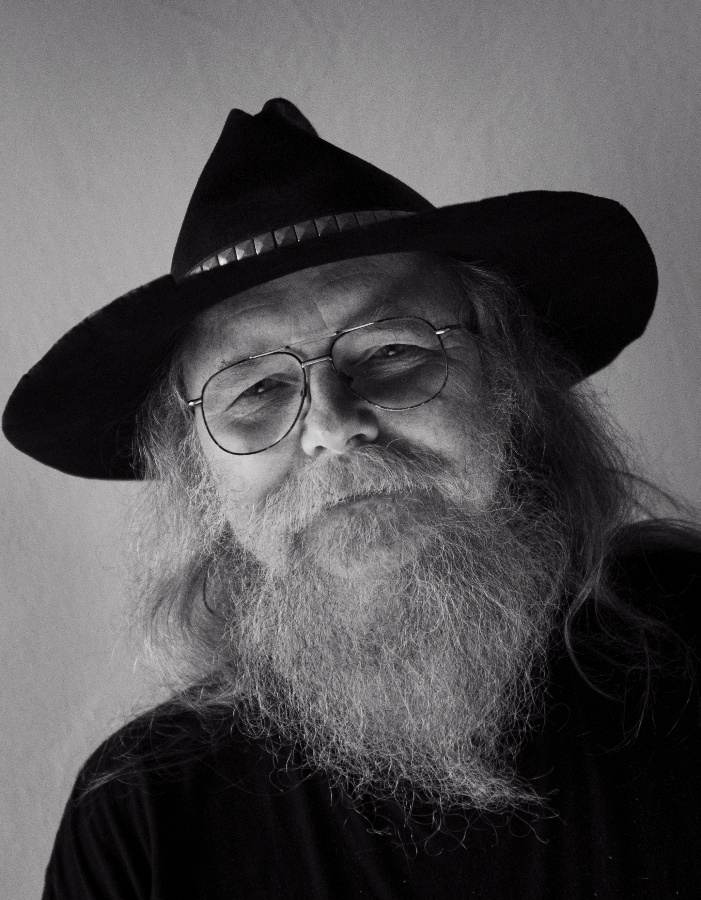

František "Čuňas" STÁREK (*1952)

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

A northern long-hair

Many things happened in the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic between 17 and 25 November 1989: hundreds of thousands of people had demonstrated against the government, the Civic Forum had existed for almost a week, representatives of the hitherto persecuted opposition had addressed the crowds, and the leadership of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia had stood down. In a nutshell, the totalitarian regime had collapsed. However, one of the “fathers of the Czech underground”, František Stárek, nicknamed Čuňas (Piggy) since his youth, was still behind bars, watching the revolution alongside other prisoners at a so-called culture room. He was greatly cheered by the evening news of 25 November: “The newscaster announced that the president had granted pardons to several dissidents and my name was one of those mentioned. There were around 70 political prisoners in the culture room and they all turned to me: ‘Bloody hell, they’ve released you!’ It was amazing. A lot of people there were inside for attempting to cross the border to the West and I had already told them we’d be going home soon. They slapped their foreheads, saying I was nuts. Only when they heard on the TV that I was getting out did they begin to take the situation somewhat seriously…”

František Stárek, a dissident, long-hair (“mánička” was the Czech word for long-haired young men) and publisher of the samizdat review Vokno, was born on 1 December 1952 in Pilsen. His family came from the village of České Libchavy, where Stáreks, farmers, had lived since at least 1574. František’s parents also had a farm, though the Communists had seized it at the start of the 1950s when collective farming began. They left with just a few bags. Mrs. Stárková was pregnant. They then lived in Teplice in north Bohemia. “It was pretty rough there (…) The men worked hard. They worked in mines, where their lives were on the line, and that carried over into their civilian lives. Things guys would in those days have slapped each other over in Prague were sorted out using knives. On top of that we were the first generation of children who had grown up there.”

When František was eight his father died of a heart attack, leaving his mother alone with three children. At a relatively early age František got into The Beatles, acquired the nickname Čuňas from friends and began his first “fight for freedom”, as yet just at school: “From around sixth grade myself and a few others led a struggle over the length of our hair. Sometimes the principal would catch us, give us two crowns and say: you, you, you, to the barbers! (…) Hair started to become very important for us.” To explain, the long-hairs soon weren’t just annoying their teachers but were being hounded by the police. Special decrees were issued in connection with them, they weren’t served in pubs, etc. In the Communist regime long hair wasn’t just a fashion – it was a symbol of resistance.

In 1968 Stárek enrolled at a secondary vocational school focused on mining in Duchcov. It was there he experienced the Soviet occupation and the start of normalisation. He passed his school leaving exams while wearing a short-haired wig. As he hadn’t received the recommendations necessary for further study, he considered escaping to the West. However, at that time the core of the north Bohemian “workers’” underground was just taking shape. Stárek was inexorably drawn into the opposition, though he wouldn’t have employed such an exalted term in those days.

At that time the underground had two main centres: Prague and north and north-western Bohemia. It’s guiding spirit was Ivan Martin Jirous, the poet, art historian and artistic leader of the band The Plastic People of the Universe. The informal cultural “movement”, which is hard to define more precisely, was centred around culture that wasn’t officially approved and was therefore subject to harassment. It brought together intellectuals, artists and young workers who shared a desire to live as they wished, a willingness to stand outside established society and a resolve to forego a career, as pursing one required undignified concessions. The Communist apparatus regarded such independent activities as a threat. However, the more they attacked the Czech counterculture, the more its members became their dyed-in-the-wool enemies.

In the first half of the 1970s František Stárek worked for around a year in Prague, where he made many friends. Then he returned home. “The north was actually one big city. Teplice is 15 kilometres from Ústí but between them stretches an industrial zone so you can’t say where one city ends and the other begins. So all the long-hairs knew one another. We went to the same pubs, we knew where the rock concerts were. After one unofficial exhibition in Mariánské Lázně I wrote a kind of text, a response, which I sent to the people who organised it in Prague. We began to exchange letters. It expanded and then I snapped it into a bundle. It was my first samizdat collection. Soon the idea of a magazine was born. (…). But we didn’t manage to get it out in time.”

The second festival of the second culture took place in Bojanovice in 1976. After it members of the Plastic People and other underground musicians and organisers were arrested. In September Ivan Martin Jirous, Pavel Zajíček, Svatopluk Karásek and Vratislav Brabenec went on trial and were convicted over their cultural activities (“disturbing the peace” in the Bolshevik terminology). In Pilsen at the same time and for the same reasons František Stárek was convicted alongside Karel Havelka and Miroslav Skalický for the crime of “disturbing the peace in an organised group”. Stárek got an eight-month sentence that was then communed to conditional release. He had spent six months in custody in Pilsen. He became a dissident.

At the start of 1977 Stárek was focused on organisational work linked to Charter 77, which he signed the same year, in part out of solidarity because it was effectively comprised of people who had previously come together just to support the underground. Signing the Charter brought him a change of employment status (from a geophysics technician he became a so-called figurant, meaning an unqualified worker) and even closer secret police attention. In 1979 Stárek began publishing the samizdat (privately produced and distributed) review Vokno, which became the underground’s main arts news magazine. By samizdat standards it came out in very large runs: “It was clear to us that just copying it on a typewriter wouldn’t suffice. One guy from Teplice taught at the Office Equipment enterprise and he secretly brought out one part of a mimeograph after the other until he had even smuggled out the roller and assembled the machine for two days in our cellar. (…) Having a mimeograph at home was like having a bomb…” After all, all the mimeographs in Czechoslovakia at that time were registered and overseen by officials.

By 1981 five issues of Vokno had been published. In the same period František Stárek cofounded a “commune” in Nová Víska. He and a number of friends bought a large farm where they lived together. They organised concerts and other arts events in the barn. However, the persecution intensified. It was fierce. In 1981 the authorities simply expropriated the house at Nová Víska and on 10 November 1981 František Stárek was arrested again over the samizdat along with Ivan Jirous, Michal Hýbek and Jiří Frič. After almost a year in custody he received as the initiator of an organised group two and a half years in prison under the notorious article 202 (on disturbing the peace) plus two years of so-called protective supervision.

From the court Stárek was taken to the Bytíz prison in the Příbram area. As to how he handled being in prison, he replies laconically. “Well you know, I was able to do time…” He was used to manual labour while his experience of the toughness of Teplice helped as he was able to get on with seasoned criminals. He attempted “following the example of revolutionaries” to use prison to study. “It occurred to me that as the editor-in-chief of Vokno that I was poorly educated, so I wanted to supplement it (…). Admittedly the library had been cleared of ‘politically undesirable’ literature. But because the screws were stupid they didn’t do it thoroughly, so a couple of quality items remained there (…). Also in those days I was interested in Renaissance painting and I clipped out various paintings and drawings from magazines. The prisoners started coming to see me. They borrowed those clippings and I didn’t know why – until I met a guy who had a motif from a drawing by Albrecht Dürer tattooed on his chest...” As regards work, in terms of quotas and the unhealthy environment conditions were similar in normalisation prisons to what they had been in 1950s jails and labour camps. Stárek first worked in a life-endangering workshop producing lead pellets before managing to be transferred to a group of prisoners making wooden pallets.

When he was released from prison he faced so-called protective supervision: compulsory regular reporting to a police station, regular home searches, a ban on leaving the immediate vicinity of one’s home without permission. However, despite this František Stárek revived the Vokno review. On top of that he and his friends began publishing samizdat books, the Voknoviny information bulletin and even a video magazine. He was then a full-time dissident, working for Charter 77, the Committee for the Defence of the Unjustly Persecuted and Polish-Czechoslovak Solidarity. He went to prison for the third time in February 1989, when he and his wife Iva Vojtková were convicted in one of the last show trials: “Again I got two and a half years and again two years of protective supervision. That was the standard punishment for being editor-in-chief of Vokno.”

Around the same time the StB produced Kamelot, a TV propaganda programme dedicated to František Stárek. Though it was meant to discredit him among intelligent people it primarily evoked derision and greater interest. Stárek first saw, or rather heard, the programme in prison: “As a prisoner it was compulsory to watch the evening news. But of course I wasn’t allowed to watch the entertainment later, which didn’t bother me at all. But because I knew that that day they were meant to broadcast a news programme on the activities of ‘rightist elements’ I was curious. I arranged with one of the prisoners that I would go and stand behind the nick and when the show was on he’d come and tell me who it was about. In a while the door flew open and the guy shouted: ‘Bloody hell! It’s about you!’ So I asked him to at least turn the sound well up.”

As mentioned above, at the end of November 1989 František Stárek received a presidential pardon. He took part in the revolution and soon joined the secret service, where he worked until 2007. Today he is involved in a research and documentation project on the history of the Czechoslovak underground and is an employee of the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes.

Text by Adam Drda