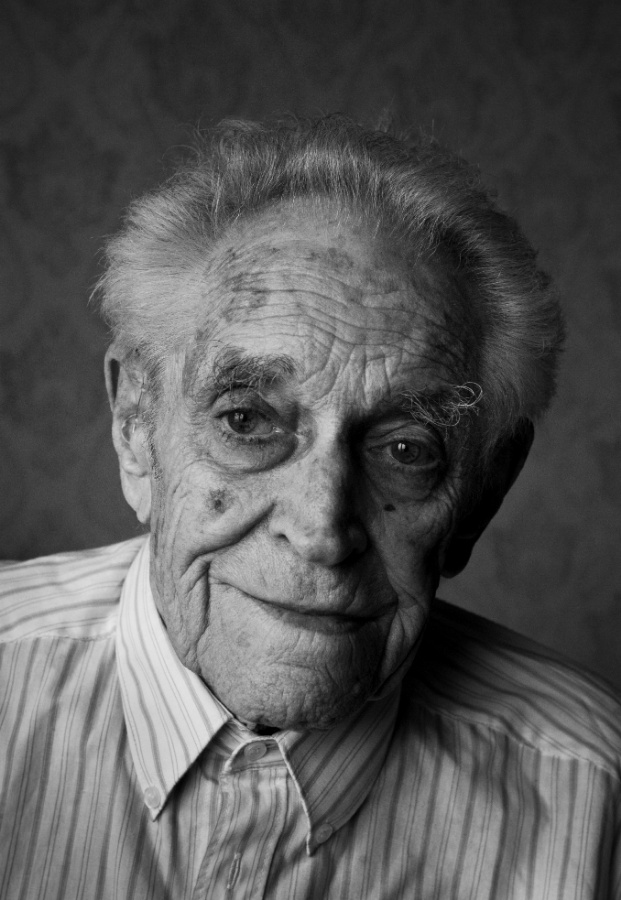

Pavel BRANKO (*1921)

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

Decisions at the crossroads of life

Pavel Branko first made an impact as a journalist in the resistance, when at a young age he became editor-in-chief of the anti-fascist magazine Mor ho. During the Slovak state two members of his resistance group received the death sentence. Branko himself survived the end of the war in Mauthausen. Though a committed Communist in the First Republic, he quit the party in protest in 1949. The film critic and journalist outlined his story in the tellingly titled autobiography Proti proudu (Against the Current). “George Orwell formulated a thesis that I dubbed the ‘Orwell constant’. This states that in every society 10 percent of people want to change the world and 10 percent are always and in all circumstances against anybody changing it. And 80 percent have families, which makes them the eternal silent majority,” he says. Branko was never of their number.

Throughout his life he has always been a lone wolf and individualist, almost always in opposition to the majority. Just as it is hard to categorise him, it is not easy to identify the coordinates of the place of his birth on 27 April 1921. It was on board a ship in the Mediterranean sailing under a French flag. He was born around three days before it docked in Trieste.

His parents Marta and Daniel were then returning to a new homeland, the Czechoslovak Republic. They had travelled all the way from Irkutsk, where they met. She was fleeing the Bolsheviks and he was a former Austrian-Hungarian POW. They had sailed half the world to reach their new homeland.

“A ship is the sovereign territory of the state under whose flag it sails. I was never a French citizen. I could have applied for citizenship up to the age of 21, but I never did,” says Branko.

The family first settled in Hačava in Slovakia before later moving to the outskirts of Bratislava and then Trnávka. It was referred to then as Masaryk’s colony, in view of the fact most inhabitants were Czech.

Branko got the urge to write very young, largely thanks to the Jules Verne books he devoured. He was also inspired by a secondary school professor, the eminent literary scientist Milan Pišút, who encouraged his hesitant early writings. As a grammar school student in Brno, Branko began following the turbulent political events of the time.

“From the early 1930s fascism was starting to expand around Europe. It first triumphed in Germany, then Spain. As a young man I felt it very keenly. Naturally if I was against something, I also had to be for something – and I was for socialism,” he says, adding that he felt part of the left-wing cultural current of that era. For him the leaders of Czechoslovak and world culture were left-wing, which was one reason he joined the interwar Communist Party.

“For me the antithesis of expanding fascism was the Soviet Union, whose seamy side I didn’t have a clue about, though even then it was possible to find out about it. But people reach for the sources that chime with their own convictions.” When the Spanish Civil War broke out, he added, his values determined what side he stood on.

When Hitler broke up Czechoslovakia in 1939 the Slovak state and the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia were formed. His father had Jewish origins, meaning Branko faced complications.

“I completed the first two semesters of technology at university. But they didn’t take me into the second year as I couldn’t prove Aryan origins. But I didn’t join the resistance because of that discrimination – I chiefly wanted to fight against fascism,” says Branko, who had already resolved to become a journalist. He would fight with his pen.

Working with a Communist cell in Trnávka he first duplicated printed materials. But soon he developed the ambition to publish his own magazine. “It was named Mor ho. So it doesn’t refer to either the Soviet Union or purely Communist ideology but more to the tradition of Slovak resistance to the nobility.” Older classmates such as Vlado Blahovec and Pavel Scharfstein helped him to bring out the magazine, which carried pieces about the need to revive Czechoslovakia. Miloš Uhlárik, who was a generation older, also became involved. As the director of a school in Vrakun he was able to lend them a school typewriter. But it was the young Branko who oversaw the whole thing.

“I became perhaps the youngest editor-in-chief of a resistance magazine, which, however, only came out in two issues.” Its activities were soon uncovered by the Central State Security, the secret police of the Slovak state. However, they didn’t discover everything and Blahovec and Scharfstein remained at large. Despite harsh interrogations in 1942 Branko never gave his friends away.

“They stayed free and continued in the resistance. Then they fell during the Slovak National Uprising. Maybe if I had betrayed them they would have survived the war, like me. We just wouldn’t have been able to look one another in the eye.” The group, which had been arrested, were facing trial. Today it is often stated that the Tiso regime never imposed the death penalty. However, their trial proves this claim is distorted.

“When they tried us in 1942 the Germans were still before Stalingrad and nobody doubted they would conquer it and win the war. It definitely appeared to be a very likely probability. And the regime acted accordingly when it turned us local Communists from Trnávka, such small fish, into big fish. They made it into a major trial with two death sentences and two life sentences. They wanted to ingratiate themselves – they too had played a part in fascism’s victory over the Communists.” The death sentences were never carried out but the convicts were brought to Nitra prison, where a different fate awaited them. In the meantime the atmosphere was slowly changing.

“In 1944 the situation was different. Only a blind person could be unaware that it was just a matter of time before fascism fell. At that time the prison staff knew very well that the scales of history were tipping to the other side and that those that were prisoners could one day be big noises who would attain senior positions after the war. Which actually happened – among us was Viliam Široký. So there was a very liberal regime in the jail. The cells had open doors and we could walk from one to another. The wardens brought us newspapers and they also kept us abreast of what wasn’t in the papers, so we knew that the uprising had broken out. In those days we slept in our clothes and shoes so that we could join the fighting.”

However, this did not occur. The Nitra regiment under Colonel Jan Šmigovský refused to join the uprising. Liberation operations did not take place. Instead of taking part, the uprising prisoners were headed elsewhere. Three months before the end of the war the Slovak state regime placed them in the hands of the Gestapo. When the rumble of Soviet artillery could be heard, the prisoners were moved to Bratislava. From there they were carried in five transports to Nazi concentration camps – and four of the transports were bombarded by the unsuspecting Allies. Branko was in the fifth transport and survived, in the end reaching Mauthausen.

He remembers the hierarchy in the camp. There was even a resistance, which many internees were active in. At Mauthausen Branko met the future Communist president Antonín Novotný, who headed the records office. Around him he saw people starving to death.

“It was a kind of race against time. Anybody could see how the war would end. Whoever lived to see liberation would survive somehow,” says Branko, who like other prisoners was liberated by the US Army on 5 May 1945. He still remembers the American soldiers’ horror at what they saw. He served as an interpreter for them, having learned English from books in prison.

When he went home his mother didn’t recognise him. The one-time 65kg 20-year-old was still a 39kg skeleton several months after his return. Writing helped him to recover and he decided to make a living translating. In those days he was enraptured by cinema. With the arrival of the so-called nylon age, a wave of excellent movies that Slovakia had missed out on during fascism began to appear. He was particularly impressed by French interwar classics. He saw himself as a film critic, though this did not last long.

Shortly after the Communist takeover, in 1949, Branko, a dedicated First Republic Communist, quit the party in protest at the first judicial killings and the party’s practices, attitude to Tiso and politics and philosophy. “It created a forum that everybody that had something to hide could sign up to.”

In 1952 he escaped from civilisation into internal exile at a cottage in the High Tatras. “The cottage was isolated – it was a kind of Jack London life”. He kept his head down during the harsh 1950s. It wasn’t possible to write about film at that time so he earned a living from translating. It wasn’t until 1956 that he again started to write about cinema.

When Warsaw Pact troops invaded Czechoslovakia on 21 August 1968 he documented everything with his camera. He even captured the desperate parents of slain student Danka Košanová near Comenius University, just minutes after her tragic shooting. Shortly after the invasion he attended the Venice film festival, where he passed the photos to foreign journalists. He also gave several interviews, anonymously of course. “After all, I wanted to go back.” In Venice he was offered help with living abroad and received a job offer thanks to his excellent German.

Following his return the borders were closed and normalisation began. This left him banned from writing or translating for the next 20 years. He refused to be broken and continued translating, under somebody else’s name.

“These are the moments that Milan Richter writes about in one of his poems, The Amber Second. Making decisions at the crossroads of life in those few seconds when the traffic lights are amber.”

Pavel Branko says he has no regrets. After all he experienced the most wonderful things in the latter half of his life. If he had not returned, he wouldn’t have met his second wife Emílie, an author of fairy-tale books for children, with whom he has spent many years.

Text by Soňa Gyarfašová