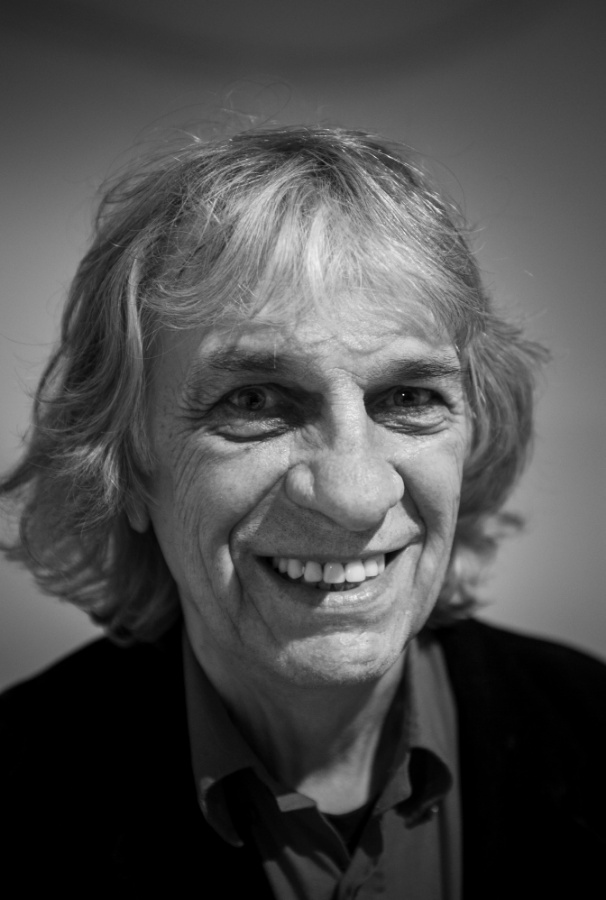

Peter KALMUS (*1953)

- Read the story (PDF, 0 kB)

A week lying on display in a coffin

“He taught me how to drive and gave me rides in a sports car. We smoked cigarettes together and he took me to a strip show,” says Peter Kalmus of the year 1968, which was a turning point not only for Czechoslovakia but also for him. Then 15, he met his biological father for the first time. This influenced the whole life of the future artist, who became famous in Slovakia for happenings protesting the legacy of two totalitarian regimes.

Kalmus spent his first few years with his mother and grandmother on a high rise estate in Piešťany. It was a Catholic district with two Evangelical families. Other children jeered, calling him a “Jew”, though he didn’t quite understand what that meant. Or why some of them threw stones at him. “I really felt like a bastard who didn’t belong anywhere,” he said in The Dissidents, a documentary by Marek Škop.

Kalmus likes to say he was born the year Stalin and Gottwald died. The date was 28 August 1953. Only gradually did he learn about his parents’ story. It was a great love story but quickly ran its course. Perhaps in part because of the era in which they met. His mother, an Evangelical, married his father, a Jew who had fled Germany because of Hitler. They survived the Holocaust in Slovakia by hiding. Though they lived to see the end of the war, the marriage didn’t last long.

In 1962, Kalmus moved with his mother to Košice. He later enrolled at a vocational school in Svit. However, he pined for the city so moved back to Košice to attend a transport-focused vocational school. But more than his studies he enjoyed the liberal atmosphere of the 1960s: freedom, art, rock’n’roll.

When he first had an opportunity to meet his father, with whom he had never lived, the teenager was somewhat reluctant. In the end he became a new friend. However, the nascent father-son relationship was interrupted by the Warsaw Pact invasion. He recalls how he and his father created and placed a work of his on a city square. It featured a dead hen on a gallows and the menacing slogan I’d rather take my life than shit out eggs for the Russians. People were up in arms at the time.

In Košice, locals actively stood up to the tanks and soldiers, erecting barricades and lobbing bricks and Molotov cocktails at armoured vehicles. On the first day of the invasion six people died in the city Kalmus called home.

The dead hen on a gallows he produced with his father was his first artistic happening. He continues to make crude reference to totalitarian symbols to this day. Father and son tore a hammer and sickle down from a monument to the fallen on Náměstí osvoboditelů. The despised symbol soon divided them. The father, in the regime’s sights as an enemy of the state, capitalised on the open borders to emigrate to West Germany, where he began a new life.

The two didn’t meet again for another 20 years. The son, shaken by 1968, a year in which Czechoslovakia gained and lost hope and he gained and lost a father, stood out amid the grey of normalisation. At that time he was already establishing ties with the Prague underground. Ivan Martin Jirous of The Plastic People of the Universe, with whom he held lengthy conversations, proved an inspiration. Jirous helped him reach the conclusion that totalitarian regimes mainly blackmail people via their families. If you want to be completely free you can’t have anything to lose, so there was no point building up a career under such a regime.

Kalmus consistently refused to go to the polls to vote for the only permitted party, the Communist Party, and also adamantly banned his first wife from doing so. However, living under a repressive regime took a very heavy toll and he attempted suicide in 1980. If it had worked out, he had requested that a death notice for him featuring black cubes be sent to an exhibition in Spain. He survived and kept doing art.

In December 1980, when John Lennon was murdered by deranged fan Mark David Chapman, he produced a granite tablet commemorating his life, placing it during the night in the fountain by Košice’s theatre.

“They took the tablet. They brought me to a police station and questioned me in connection to it. I confessed to having made it and requested that they return it, as it was my property. They agreed, but I wasn’t allowed to carry it through the streets just like that, as it was propaganda for the West. So I wrapped it in a newspaper – Rudé právo – and brought it home,” he said in an interview with the Košice newspaper Korzár in 2010.

The State Security registered him as a hostile individual in 1988. However, his file doesn’t exist, having been destroyed by the secret police in the same year they set it up. A year later, in 1989, when the regime was collapsing, he became involved in the Košice Civic Forum. He also found time to wrap a black plastic bag around a statue of Klement Gottwald. He continued to have ideas for artistic protest happenings even after the Velvet Revolution.

He is known in Slovakia as somebody who enjoys grabbing the headlines at any price. People were shocked when he lay displayed in a coffin at the Stoka theatre for a week. The motif of death also figures in director Adam Hanuljak’s biographical film The Kalmus Case.

Another motif of his art, however, is coming to terms with two totalitarian systems. In 1988 he began wrapping stones in brass wire – one for every Jew deported in the Slovak state period. Eighty thousand in total. Some of the stones became part of Zvolen’s Park of Noble Souls, a tribute to those who saved lives. The rest have symbolically been placed in four glass receptacles in Lučenec’s revived synagogue.

The one-time signatory of the Several Sentences appeal has also modified busts. He painted a statue of the dyed-in-the-wool Communist poet Ladislav Novomeský black and later covered it in a sweater bearing the words New York. When a bust of János Esterházy was unveiled in his native Košice he protested on the grounds that the politician had welcomed Horthy’s fascist troops and was undeserving of glory. He attempted to wrap the statue in toilet paper and was set upon by a number of those in attendance.

Photos of Kalmus and Lorenz, two Košice artists, by a monument to Vasil Biľak in Krajná Bystrá daubed with red paint sparked a nationwide discussion. They had gone to Biľak’s hometown shortly after the unveiling of the monument and wrote “bastard” on it. They also painted over a plaque to Communist prosecutor Ján Pješčák, who played a role in the judicial murder of Sergeant Alois Jeřábek in 1953, and have thrown mud over statues and plaques commemorating the president of the wartime Slovak state, Tiso. During one of his art happenings Kalmus put red lipstick on a statue of Tiso as well as daubing red cheeks on it.

Incidentally, he has an unusual relationship to statues. He likes taking photos of himself with them in various erotic poses.

In 2017 he published a book on his life and work with the distinctive title Dost bylo Kalmuse (Enough Kalmus Already).

Text by Soňa Gyarfašová